Altar

One of the most important surviving Roman altars is the Ara Pacis, dedicated by Augustus Caesar at the beginning of the Pax Romana to the goddess of peace, Pax.Altars [a] in the Hebrew Bible were typically made of earth[3] or unwrought stone.

The remains of three rock-hewn altars were discovered in the Land of Israel: one below Tel Zorah, another at the foot of Sebastia (ancient Samaria), and a third near Shiloh.

In Catholic and Orthodox Christian theology, the Eucharist is a re-presentation, in the literal sense of the one sacrifice of Christ on the cross being made "present again".

The Christian replication of the layout and the orientation of the Jerusalem Temple helped to dramatize the eschatological meaning attached to the sacrificial death of Jesus the High Priest in the Epistle to the Hebrews.

This diversity was recognized in the rubrics of the Roman Missal from the 1604 typical edition of Pope Clement VIII to the 1962 edition of Pope John XXIII: "Si altare sit ad orientem, versus populum ..."[18] When placed close to a wall or touching it, altars were often surmounted by a reredos or altarpiece.

"[21](303) The altar, fixed or movable, should as a rule be separate from the wall so as to make it easy to walk around it and to celebrate Mass at it facing the people.

[29][30][31] Some Methodist and other evangelical churches practice what is referred to as an altar call, whereby those who wish to make a new spiritual commitment to Jesus Christ are invited to come forward publicly.

This is a ritual in which the supplicant makes a prayer of penitence (asking for his sins to be forgiven) and faith (called in evangelical Christianity "accepting Jesus Christ as their personal Lord and Saviour").

When a stone altar was placed in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Cambridge after rebuilding works in 1841, a case was brought in the Court of Arches which resulted in an order to remove it and replace it with a wooden communion table.

Nonetheless, the continued popularity of communion rails in Anglican church construction suggests that a sense of the sanctity of the altar and its surrounding area persists.

In most cases, moreover, the practice of allowing only those items that have been blessed to be placed on the altar is maintained (that is, the linen cloth, candles, missal, and the Eucharistic vessels).

In Greek, the word βωμός (bômós) can mean an altar of any religion or, in a broader sense, the area surrounding it; that is to say, the entire sanctuary.

[h]A plain linen covering (Greek: Katasarkion, Slavonic: Strachítsa) is bound to the Holy Table with cords; this is never removed once the altar is consecrated, and is considered to be its “baptismal garment”.

Above this first linen cover is a second, ornamented altar cloth (Indítia), often of a brocade in the liturgical color reflecting the feast or changing ecclesiastical season.

Atop the altar is the tabernacle (Kovtchég), a miniature shrine sometimes built in the form of a church, inside of which is a small ark containing the reserved sacrament for use in communing the sick.

Also kept on the altar is the Gospel Book, under which is the antimension, a silken cloth imprinted with an icon of Christ being prepared for burial, with a relic sewn into it and the signature of the bishop.

A simpler cloth called the ilitón is wrapped around the antimension to protect it, and symbolizes the “napkin” tied around the face of Jesus when he was laid in the tomb (thus a companion to the strachitsa).

On the northern side of the sanctuary stands another, smaller altar, known as the Table of Oblation (Prothesis or Zhértvennik) at which the Liturgy of Preparation takes place.

The ultimate example is the carroccio of the medieval Italian city states, which was a four-wheeled mobile shrine pulled by oxen and sporting a flagpole and a bell.

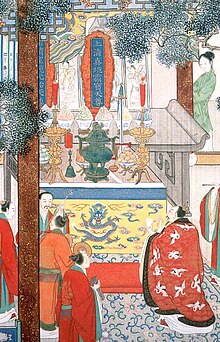

Strict traditions and different sects describe the items offered and the ritual involved in the temples, but folk custom in the homes is much freer.

[40]) This may be done at home, or in a temple, or outdoors; by an ordinary person, or a professional (such as a Taoist priest); and the altar may feature any number of deities or ancestral tablets.

In Japan, the butsudan is a wooden cabinet with doors that enclose and protect a religious image of the Buddha or the Bodhisattvas (typically in the form of a statue) or a mandala scroll, installed in the highest place of honor and centered.

A butsudan usually contains subsidiary religious items—called butsugu—such as candlesticks, incense burners, bells, and platforms for placing offerings such as fruit.

The Chinese and Koreans built walls and doors around the statues to shield them from the weather and also adapted elements of their respective indigenous religions.

A physical area is demarcated with branches of green bamboo or sakaki at the four corners, between which are strung sacred border ropes (shimenawa).

In the center of the area a large branch of sakaki festooned with sacred emblems (hei) is erected as a yorishiro, a physical representation of the presence of the kami and toward which rites of worship are performed.

In Nordic Modern Pagan practice, altars may be set up in the home or in wooded areas in imitation of the hörgr of ancient times.

In neopaganism there is a wide variety of ritual practice, running the gamut from a very eclectic syncretism to strict polytheistic reconstructionism.

High places in Israelite (Hebrew: Bamah, or Bama) or Canaanite culture were open-air shrines, usually erected on an elevated site.

Prior to the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites in the 12th–11th century BCE, the high places served as shrines of the Canaanite fertility deities, the Baals (Lords) and the Asherot (Semitic goddesses).