Buddhahood

Buddhahood (Sanskrit: buddhatva; Pali: buddhatta or buddhabhāva; Chinese: 成佛) is the condition and state of being a Buddha.

[2] This highest spiritual state of being is also termed sammā-sambodhi (Sanskrit: samyaksaṃbodhi; "full, complete awakening") and is interpreted in many different ways across schools of Buddhism.

In Theravāda Buddhism, a Buddha is commonly understood as a being with the deepest spiritual wisdom about the true nature of reality, who has transcended rebirth and all causes of suffering (duḥkha).

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, Buddhahood is the universal goal and all Mahāyānists ultimately aim at becoming a Buddha, in order to benefit and liberate all sentient beings.

[5][6][7] Buddhism is devoted primarily to awakening or enlightenment (bodhi), Nirvāṇa ("blowing out"), and liberation (vimokṣa) from all causes of suffering (duḥkha) due to the existence of sentient beings in saṃsāra (the cycle of compulsory birth, death, and rebirth) through the threefold trainings (ethical conduct, meditative absorption, and wisdom).

According to the standard Buddhist scholastic understanding, liberation arises when the proper elements (dhārmata) are cultivated and when the mind has been purified of its attachment to fetters and hindrances that produce unwholesome mental factors (various called defilements, poisons, or fluxes).

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, Buddhahood is the universal goal and all Mahāyānists ultimately aim at becoming a Buddha, in order to benefit and liberate all sentient beings.

In Theravāda Buddhism, Buddha refers to one who has reached awakening or enlightenment (bodhi) through their own efforts and insight, without a teacher to point out the Dhārma.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, a Buddha is seen as a transcendent being who has extensive powers, such as omniscience, omnipotence, and whose awakened wisdom (buddha-jñana) is all pervasive.

Thus, the Ratnagotravibhāga (Analysis of the Jeweled Lineage), a key Mahāyāna treatise, defines the Buddha as "the uncompounded (asamskrta), and spontaneous (anabhoga) Dharmakāya" and as "self-enlightened and self-arisen wisdom (jñana), compassion and power for the benefit of others.

The Theravāda Buddhist tradition generally sees the Buddha as a supreme person who is neither a God in the theistic sense, nor a deva, nor a regular human.

This view of the Buddhas a supreme person with many superpowers, but which has a physical body that has many limitations of a human form was also shared by other early Buddhist schools, like the Sarvāstivāda and the Dharmaguptaka.

[21] Because he has attained the highest spiritual knowledge, the Buddha is also identified with the Dhārma (the most fundamental reality) In the Vakkali Sutta (SN 22.87).

[22] In the early Buddhist schools, the Mahāsāṃghika branch regarded the buddhas as being characterized primarily by their supramundane (lokottara) nature.

[24] Of the 48 special theses attributed by the Indian scholar Vasumitra to the Mahāsāṃghika sects of Ekavyāvahārika, Lokottaravāda, and Kukkuṭika, 20 points concern the supramundane nature of buddhas and bodhisattvas.

[31] Guang Xing writes that the Acchariyābbhūtasutta of the Majjhima Nikāya along with its Chinese Madhyamāgama parallel is the most ancient source for the Mahāsāṃghika view.

The Chinese version even calls him Bhagavan, which suggests the idea that the Buddha was already awakened before descending down to earth to be born.

Guang Xing describes the Buddha in Mahāyāna as an omnipotent and almighty divinity "endowed with numerous supernatural attributes and qualities".

His life and death were a "mere appearance," like a magic show; in reality, the Buddha still exists and is constantly helping living beings.

"[43] In a similar fashion, Jack Maguire, a Western monk of the Mountains and Rivers Order in New York, writes that Buddha is inspirational based on his humanness: A fundamental part of Buddhism's appeal to billions of people over the past two and a half millennia is the fact that the central figure, commonly referred to by the title "Buddha", was not a god, or a special kind of spiritual being, or even a prophet or an emissary of one.

All Buddhist traditions hold that a Buddha is fully awakened and has completely purified his mind of the three poisons of craving, aversion and ignorance.

The inscription made when Emperor Asoka at Nigali Sagar in 249 BCE records his visit, the enlargement of a stupa dedicated to the Kanakamuni Buddha, and the erection of a pillar.

[89][90] According to Xuanzang, Koṇāgamana's relics were held in a stupa in Nigali Sagar, in what is now Kapilvastu District in southern Nepal.

[91] The historical Buddha, Gautama, also called Shakyamuni ("Sage of the Shakyas"), is mentioned epigraphically on the Pillar of Ashoka at Rummindei (Lumbini in modern Nepal).

The Brahmi script inscription on the pillar gives evidence that Ashoka, emperor of the Maurya Empire, visited the place in 3rd-century BCE and identified it as the birth-place of the Buddha.

(He) made the village of Lummini free of taxes, and paying (only) an eighth share (of the produce).The Pali literature of the Theravāda tradition includes tales of 28 previous Buddhas.

In countries where Theravāda Buddhism is practiced by the majority of people, such as Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, it is customary for Buddhists to hold elaborate festivals, especially during the fair weather season, paying homage to the last 28 Buddhas described in the Buddhavamsa.

According to Buddhist scripture, Metteyya will be a successor of Gautama who will appear on Earth, achieve complete enlightenment, and teach the pure Dharma.

They are generally seen as living in other realms, known as buddha-fields (Sanskrit: buddhakṣetra) or pure lands (Ch: 淨土; p: Jìngtǔ) in East Asian Buddhism.

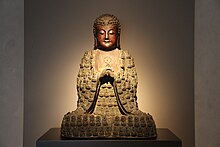

The exactly design and style of these features vary regionally but most often they are elements of list of thirty-two physical characteristics of the Buddha called "the signs of a great man" (Skt.