Altarpiece

An altarpiece is an work of art in painting, sculpture or relief representing a religious subject made for placing at the back of or behind the altar of a Christian church.

Altarpieces were one of the most important products of Christian art especially from the late Middle Ages to the era of Baroque painting.

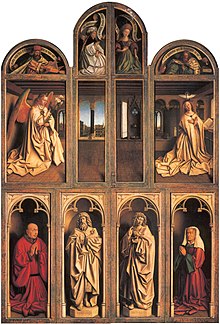

Often this was the normal view shown in the church, except for Sundays and feast days, when the wings were opened to display the main image.

[4] Many altarpieces have now been removed from their church settings, and often from their elaborate sculpted frameworks, and are displayed as more simply framed paintings in museums and elsewhere.

In the first several centuries of large Christian churches being built, the altar tended to be further forward (towards the congregation) in the sanctuary than in the later Middles Ages (a position to which it returned in the 20th century) and a large altarpiece would often have blocked the view of a bishop's throne and other celebrants, so decoration was concentrated on other places, with antependiums or altar frontals, or the surrounding walls.

[7] Many early altarpieces were relatively simple compositions in the form of a rectangular panel decorated with series of saints in rows, with a central, more pronounced figure such as a depiction of Mary or Christ.

An elaborate example of such an early altarpiece is the metal and enamel Pala d'Oro in Venice, extended in the 12th century from an earlier altar frontal.

[9] These altarpieces were influenced by Byzantine art, notably icons, which reached Western Europe in greater numbers following the conquest of Constantinople in 1204.

[6] In the early 14th century, the winged altarpiece emerged in Germany, the Low Countries, Scandinavia, the Baltic region and the Catholic parts of Eastern Europe.

Instead of being centred on a single holy figure, altarpieces began to portray more complex narratives linked to the concept of salvation.

In Italy both stone retables and wooden polyptychs were common, with individual painted panels and often (notably in Venice and Bologna) with complex framing in the form of architectural compositions.

[6] In Spain, altarpieces developed in a highly original fashion into often very large, architecturally influenced reredos, sometimes as tall as the church in which it was housed.

This much height typically required a composition with an in aria group to fill the upper part of the picture space, as in Raphael's Transfiguration (now Vatican), though The Raising of Lazarus by Sebastiano del Piombo (now London) is almost as tall, using only a landscape at the top.

[11] The Reformation initially persisted with the creation of new some altarpieces reflecting its doctrines, sometimes using portraits of Lutheran leaders for figures such as apostles.

The Reformation regarded the Word of God – that is, the gospel – as central to Christendom, and Protestant altarpieces were often painted biblical text passages, increasingly at the expense of any pictures.

If funds allowed several altarpieces were commissioned for Baroque churches when they were first built or re-fitted, for the main and side-altars, giving the whole interior a consistent style.

Examples by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680), the leading Baroque sculptor of his day, include his Ecstasy of Saint Teresa in Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome, and his sculpted concetto around the painting by Guillaume Courtois in Sant'Andrea al Quirinale.

[4] German Baroque and Rococo altarpieces also revived the local taste for sculpture, with the figures in many examples (usually in stucco) spreading around the whole upper level of the church.

At least in the 15th century, altarpieces for main or high altars were required by canon law to be free-standing, allowing passage behind them,[22] while those for side chapels were often attached to, or painted, the wall behind.

Much smaller private altarpieces, often portable, were made for wealthy individuals to use at home, often as folding diptychs or triptychs for safe transport.

[23] Matters evolved differently in Eastern Orthodoxy, where the iconostasis developed as a wide screen composed of large icons, placed in front of the altar, with doors through it, and running right across the sanctuary.