Crusading movement

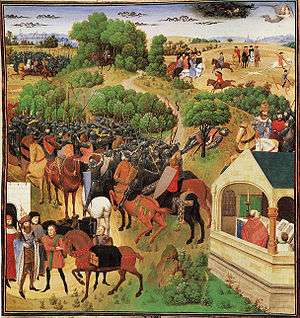

The campaigns to reclaim the Holy Land were the ones that attracted the greatest support, but the crusading movement's theatre of war extended wider than just Palestine.

Crusades were waged in the Iberian Peninsula, in northeastern Europe against the Wends, and in the Baltic region; other campaigns were fought against those the church considered heretics in France, Germany, and Hungary, as well as in Italy against opponents of the popes.

By definition, all crusades were waged with papal approval and through this reinforced the Western European concept of a single, unified Christian church under the Pope.

In the latter part of the 11th century, Christianity's requirement to avoid violence was still a significant issue for the warrior class, so Gregory VII offered them a potential solution.

[12][13] When Urban II launched the First Crusade at Clermont in November 1095, he made two offers to those who would travel to Jerusalem and fight for control of the sites Christians considered sacred.

[18][19] It was in the 1213 papal bull called Quia maior that he reached out beyond the noble warrior class, offering all Christians the opportunity to redeem their vows without going on crusade.

The argument was that Rome was the estate of St Peter, so the popes' Italian campaigns were considered defensive and fought for the preservation of Christian territory.

In feudal Europe, the formation of disciplined units was a significant challenge, strategic approaches and institutional frameworks were underdeveloped, and power was too fragmented to support cohesive organisation.

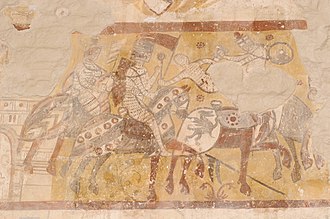

While the church feared the warrior class, it still needed to co-opt its power and demonstrated this symbolically through the development of liturgical blessings to sanctify new knights.

These orders became Latin Christendom's first professional fighting forces and played a major part in the defence of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other crusader states.

[58] Historian Jean Flori suggests that the Church's intent was to eliminate its rivals' ideology in order to justify Christianity's participation in aggressive and violent conflicts.

[64] The origins of the crusading movement lie within the nature of Western Christian society in the late eleventh century rather than any external provocation, despite intense propaganda about the Turks' actions.

While the Seljuk Turks' incursions into Anatolia increased after the Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, Islam had controlled Jerusalem since 638 without eliciting a comparable Western reaction.

Examples of Epic poetry include the Chanson d'Antioche describing the events in the 1268 siege of Antioch and Canso de la Crozada about the crusading against the Cathars in Southern France.

But there are examples in the literary language of southern France, Occitan, French, German, Spanish, and Italian that touch on the topic in an allegorical that date from the later half of the century.

A more atomized society meant that literature tended to rather praise individual deeds of heroes like Charlemagne and the actions of major families.

He demonstrates that the term pueri referred to youths or individuals of low social status, and that this movement was not solely composed of children but included marginalized groups like shepherds and agricultural workers.

Dickson's work interprets the "Children's Crusade" as a form of social critique driven by a desire to return to apostolic simplicity and dissatisfaction with societal leaders.

Primary sources include the Würzburg Annals and Humbert of Romans's work De praedicatione crucis which translates as concerning the preaching of the cross.

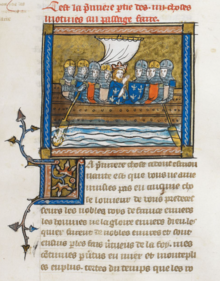

The discussions with John V Palaiologos resulted in agreement to unify the Latin, Greek Orthodox, Armenian, Nestorian, and Cypriot Maronite churches and commitments of military support for the Byzantines.

As it did the commissioning of advisory tracts reconsidering the political, financial, and military issues with luminaries like as Cardinal Bessarion dedicating their lives to the cause.

The State of the Teutonic Order became the hereditary Duchy of Prussia when the last Prussian master, Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach, converted to Lutheranism and became the first duke under oath to his uncle Sigismund I the Old of Poland.

[147] Age of Enlightenment philosophers and historians such as David Hume, Voltaire and Edward Gibbon used crusading as a conceptual tool to critique religion, civilization and cultural mores.

[148] Alternatively, Claude Fleury and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz proposed that the crusades were one stage in the improvement of European civilization; that paradigm was further developed by the Rationalists.

[150] Gibbon followed Thomas Fuller in dismissing the concept that the crusades were a legitimate defence, as they were disproportionate to the threat presented; Palestine was an objective, not because of reason but because of fanaticism and superstition.

[154][155] The historian Thomas F. Madden argues that modern tensions are the result of a constructed view of the Crusades created by colonial powers in the 19th century and transmitted into Arab nationalism.

War, to the Byzantines, was justified solely for the defence of the empire, in contrast to Muslim expansionist ideals and Western knights' notion of holy warfare to glorify Christianity.

[156] Scholars like Carole Hillenbrand assert that within the broader context of Muslim historical events, the Crusades were considered a marginal issue when compared to the collapse of the Caliphate, the Mongol invasions, and the rise of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, supplanting Arab rule.

The first modern biography of Saladin was authored by the Ottoman Turk Namık Kemal in 1872, while the Egyptian Sayyid Ali al-Hariri produced the initial Arabic history of the Crusades in response to Kaiser Wilhelm II's visit to Jerusalem in 1898.

[140] Madden argues that Arab nationalism absorbed a constructed view of the Crusades created by colonial powers in the 19th century, contributing to modern tensions.