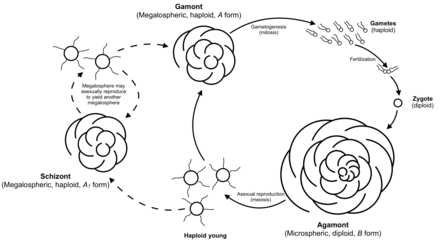

Alternation of generations

A mature sporophyte produces haploid spores by meiosis, a process which reduces the number of chromosomes to half, from two sets to one.

At maturity, a gametophyte produces gametes by mitosis, the normal process of cell division in eukaryotes, which maintains the original number of chromosomes.

Although moss and hornwort sporophytes can photosynthesise, they require additional photosynthate from the gametophyte to sustain growth and spore development and depend on it for supply of water, mineral nutrients and nitrogen.

[4] In ferns the gametophyte is a small flattened autotrophic prothallus on which the young sporophyte is briefly dependent for its nutrition.

In flowering plants, the reduction of the gametophyte is much more extreme; it consists of just a few cells which grow entirely inside the sporophyte.

Life cycles of plants and algae with alternating haploid and diploid multicellular stages are referred to as diplohaplontic.

[6] In some species, such as the alga Ulva lactuca, the diploid and haploid forms are indeed both free-living independent organisms, essentially identical in appearance and therefore said to be isomorphic.

By contrast, in all seed plants the gametophytes are strongly reduced, although the fossil evidence indicates that they were derived from isomorphic ancestors.

Here the notion of two generations is less obvious; as Bateman & Dimichele say "sporophyte and gametophyte effectively function as a single organism".

[17] The situation is quite different from that in animals, where the fundamental process is that a multicellular diploid (2n) individual directly produces haploid (n) gametes by meiosis.

[17] The diagram shown above is a good representation of the life cycle of some multi-cellular algae (e.g. the genus Cladophora) which have sporophytes and gametophytes of almost identical appearance and which do not have different kinds of spores or gametes.

Alternation of generations occurs in almost all multicellular red and green algae, both freshwater forms (such as Cladophora) and seaweeds (such as Ulva).

In the presence of water, the biflagellate sperm from the antheridia swim to the archegonia and fertilisation occurs, leading to the production of a diploid sporophyte.

Its body comprises a long stalk topped by a capsule within which spore-producing cells undergo meiosis to form haploid spores.

The life cycle of ferns and their allies, including clubmosses and horsetails, the conspicuous plant observed in the field is the diploid sporophyte.

The haploid spores develop in sori on the underside of the fronds and are dispersed by the wind (or in some cases, by floating on water).

In the spermatophytes, the seed plants, the sporophyte is the dominant multicellular phase; the gametophytes are strongly reduced in size and very different in morphology.

As the diploid phase was becoming predominant, the masking effect likely allowed genome size, and hence information content, to increase without the constraint of having to improve accuracy of DNA replication.

This view has been challenged, with evidence showing that selection is no more effective in the haploid than in the diploid phases of the lifecycle of mosses and angiosperms.

Karogamy produces a diploid zygote, which is a short-lived sporophyte that soon undergoes meiosis to form haploid spores.

[33] In some animals, there is an alternation between parthenogenic and sexually reproductive phases (heterogamy), for instance in salps and doliolids (class Thaliacea).