Althing

For 641 years, the Althing did not serve as the parliament of Iceland; ultimate power rested with the Norwegian, and subsequently the Danish throne.

To begin with, the Althing was a general assembly of the Icelandic Commonwealth, where the country's most powerful leaders (goðar) met to decide on legislation and dispense justice.

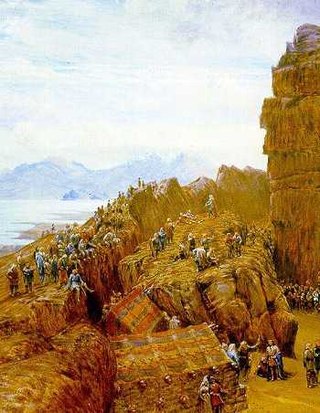

All free men could attend the assemblies, which were usually the main social event of the year and drew large crowds of farmers and their families, parties involved in legal disputes, traders, craftsmen, storytellers, and travellers.

The centre of the gathering was the Lögberg, or Law Rock, a rocky outcrop on which the Lawspeaker (lögsögumaður) took his seat as the presiding official of the assembly.

[11] By the summer of 1000, the leaders of Iceland had agreed that prosecuting close relatives for blaspheming the old gods was obligatory.

Iceland was in the midst of unrest from the spread of Christianity that was introduced by travelers and missionaries sent by the Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason.

[11] Public addresses on matters of importance were delivered at the Law Rock and there the assembly was called to order and dissolved.

The Althing of old also performed a judicial function and heard legal disputes in addition to the spring assemblies held in each district.

[4] When the Icelanders submitted to the authority of the Norwegian king under the terms of the "Old Covenant" (Gamli sáttmáli) in 1262, the function of the Althing changed.

As before, the Lögrétta, now comprising 36 members, continued to be its principal institution and shared formal legislative power with the king.

Laws adopted by the Lögrétta were subject to royal assent and, conversely, if the king initiated legislation, the Althing had to give its consent.

Towards the end of the 14th century, royal succession brought both Norway and Iceland under the control of the Danish monarchy.

With the introduction of absolute monarchy in Denmark, the Icelanders relinquished their autonomy to the Crown, including the right to initiate and consent to legislation.

Some Icelandic nationalists (the Fjölnir group) did not want Reykjavík as the location for the newly established Althing due to the perception that the city was too influenced by Danes.

Suffrage was, following the Danish model, limited to males of substantial means and at least 25 years of age, which to begin with meant only about 5% of the population.

[4] The Constitution of 1874 granted to the Althing joint legislative power with the Crown in matters of exclusive Icelandic concern.

[14] Six elected members and the six appointed ones sat in the upper chamber, which meant that the latter could prevent legislation from being passed by acting as a bloc.

[4] A constitutional amendment, confirmed on 3 October 1903, granted the Icelanders home rule and parliamentary government.

When the Constitution was amended in 1915, the royally nominated members of the Althing were replaced by six national representatives elected by proportional representation for the entire country.

[4] The union with Iceland was effectively made inoperable when the Kingdom of Denmark was occupied by Germany on 9 April 1940.

This position continued until the Act of Union was repealed, and the Republic of Iceland established, at a session of the Althing held at Þingvellir on 17 June 1944.

The country was divided into eight constituencies with proportional representation in each, in addition to the previous eleven equalization seats.