Alvin Plantinga's free-will defense

[5] Nonetheless, if Plantinga had offered no further argument, then a theologian's intuitive impressions that a contradiction must exist would have remained unanswered.

[9] Plantinga did not claim to have shown that the conclusion of the logical problem is wrong, nor did he assert that God's reason for allowing evil is, in fact, to preserve free will.

[10] Plantinga's defense has received strong support among academic philosophers, with many agreeing that it defeated the logical problem of evil.

[11][12][13][14] Contemporary atheologians[15] have presented arguments claiming to have found the additional premises needed to create an explicitly contradictory theistic set by adding to the propositions 1–4.

[13] Plantinga's free-will defense is the best known of these responses at least in part because of his thoroughness in describing and addressing the relevant questions and issues in God, Freedom, and Evil.

In this way Plantinga's approach differs from that of a traditional theodicy, which would strive to show not just that the new propositions are valid, but that the argument is sound, prima facie plausible, or that there are good grounds for making it.

[16] Thus the burden of proof on Plantinga is lessened, and yet his approach may still serve as a defense against the claim by Mackie that the simultaneous existence of evil and an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God is "positively irrational".

As it turned out, sadly enough, some of the free creatures God created went wrong in the exercise of their freedom; this is the source of moral evil.

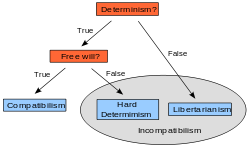

And if it were true, it would rule out the possibility of a world in which human beings make free choices, but always act in good ways.

According to Chad Meister, professor of philosophy at Bethel University, most philosophers accept Plantinga's free-will defense and thus see the logical problem of evil as having been sufficiently rebutted.

"[22] William Alston has said that "Plantinga ... has established the possibility that God could not actualize a world containing free creatures that always do the right thing.

[24] In Arguing About Gods, Graham Oppy offers a dissent, acknowledging that "[m]any philosophers seem to suppose that [Plantinga's free-will defense] utterly demolishes the kinds of 'logical' arguments from evil developed by Mackie" but continuing: "I am not sure this is a correct assessment of the current state of play.

"[25] Concurring with Oppy, A. M. Weisberger writes "contrary to popular theistic opinion, the logical form of the argument is still alive and beating.

"The concept of individual essences concedes that even if … freedom in the important sense is not compatible with causal determinism, a person can still be such that he will freely choose this way or that in each specific situation.

Given this, and given the unrestricted range of all logically possible creaturely essences from which an omnipotent and omniscient god would be free to select whom to create, … my original criticism of the free will defence holds good: had there been such a god, it would have been open to him to create beings such that they would always freely choose the good."

Further, even animals and living creatures in the wild face horrendous evils and suffering – such as burns and slow death after natural fires or other natural disasters or from predatory injuries – and it is unclear, state Bishop and Perszyk, why an all-loving God would create such free creatures prone to intense suffering.

[43] The focus on possible worlds in Plantinga's free will defense unwittingly reinvented the Molinist doctrine of middle knowledge—knowledge of the counterfactuals of human freedom, thereby precipitating a revival in the interest of Molinism.

Molinism was applied not only to the problem of evil, but also to the incarnation, providence, prayer, Heaven and Hell, perseverance in grace and so on.