Amalthea (moon)

[5] Amalthea was discovered on 9 September 1892 by Edward Emerson Barnard using the 36 inch (91 cm) refractor telescope at Lick Observatory.

[14] Its Roman numeral designation is Jupiter V. The name "Amalthea" was initially suggested by Camille Flammarion.

[4] Such appreciably nonzero values of inclination and eccentricity, though still small, are unusual for an inner satellite and can be explained by the influence of the innermost Galilean satellite, Io: in the past Amalthea has passed through several mean-motion resonances with Io that have excited its inclination and eccentricity (in a mean-motion resonance the ratio of orbital periods of two bodies is a rational number like m:n).

[5] Bright patches of less-red tint appear on the major slopes of Amalthea, but the nature of this color is currently unknown.

The asymmetry is probably caused by the higher velocity and frequency of impacts on the leading hemisphere, which excavates a bright material—presumably ice—from the interior of the moon.

[5] In the end, Amalthea's density was found to be as low as 0.86 g/cm3,[6][20] so it must be either a relatively icy body or very porous "rubble pile" or, more likely, something in between.

Recent measurements of infrared spectra from the Subaru telescope suggest that the moon indeed contains hydrous minerals, indicating that it cannot have formed in its current position, since the hot primordial Jupiter would have melted it.

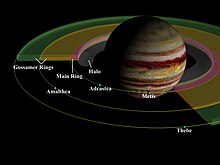

[23] Due to tidal force from Jupiter and Amalthea's low density and irregular shape, the escape velocity at its surface points closest to and furthest from Jupiter is no more than 1 m/s, and dust can easily escape from it after, for example, micrometeorite impacts; this dust forms the Amalthea Gossamer Ring.

Amalthea's orbital period is only slightly longer than its parent planet's day (about 20% in this case), which means it would cross Jupiter's sky very slowly.

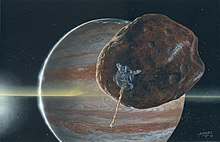

[b] Science journalist Willy Ley suggested Amalthea as a base for observing Jupiter, because of its nearness to the planet, almost-synchronous orbit, and small size making a landing easy.

[28] From the surface of Amalthea, Jupiter would look enormous: at 46 degrees across,[c] it would appear roughly 85 times wider than the full moon from Earth.

Galileo made its final satellite fly-by at a distance of approximately 244 km (152 mi) from Amalthea's center (at a height of about 160–170 km) on 5 November 2002, permitting the moon's mass to be accurately determined, while changing Galileo's trajectory so that it would plunge into Jupiter in September 2003 at the end of its mission.

Amalthea is the setting of several works of science fiction, including stories by Arthur C. Clarke, James Blish, and Arkady and Boris Strugatsky.