Rings of Jupiter

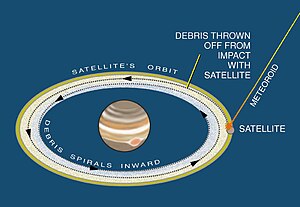

[6] The main and halo rings consist of dust ejected from the moons Metis, Adrastea and perhaps smaller, unobserved bodies as the result of high-velocity impacts.

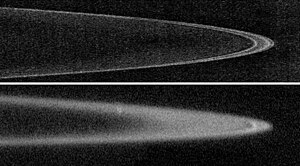

[2] High-resolution images obtained in February and March 2007 by the New Horizons spacecraft revealed a rich fine structure in the main ring.

The total mass of the ring system (including unresolved parent bodies) is poorly constrained, but is probably in the range of 1011 to 1016 kg.

One explanation is that a small moon recently crashed into Himalia and the force of the impact ejected the material that forms the ring.

[2][5][6][8] In 2022, dynamical simulations suggested that the relative meagreness of Jupiter's ring system, compared to that of the smaller Saturn, is due to destabilising resonances created by the Galilean satellites.

The fine structure of the main ring was discovered in data from the Galileo orbiter and is clearly visible in back-scattered images obtained from New Horizons in February–March 2007.

[7][13] The early observations by Hubble Space Telescope (HST),[3] Keck[4] and the Cassini spacecraft failed to detect it, probably due to insufficient spatial resolution.

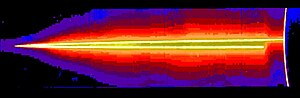

[14] Observed in back-scattered light the main ring appears to be razor thin, extending in the vertical direction no more than 30 km.

[2] One of the discoveries of the Galileo orbiter was the bloom of the main ring—a faint, relatively thick (about 600 km) cloud of material which surrounds its inner part.

[2] Detailed analysis of the Galileo images revealed longitudinal variations of the main ring's brightness unconnected with the viewing geometry.

[15] While no satellites larger than 0.5 km were found, the cameras of the spacecraft detected seven small clumps of ring particles.

Spectra of the main ring obtained by the HST,[3] Keck,[16] Galileo[17] and Cassini[8] have shown that particles forming it are red, i.e. their albedo is higher at longer wavelengths.

[16] The properties of the main ring can be explained by the hypothesis that it contains significant amounts of dust with 0.1–10 μm particle sizes.

[9][12] However, larger bodies are required to explain the strong back-scattering and fine structure in the bright outer part of the main ring.

[19] The dust scatters light preferably in the forward direction and forms a relatively thick homogenous ring bounded by the orbit of Adrastea.

[9] In contrast, large particles, which scatter in the back direction, are confined in a number of ringlets between the Metidian and Adrastean orbits.

[9][12] The dust is constantly being removed from the main ring by a combination of Poynting–Robertson drag and electromagnetic forces from the Jovian magnetosphere.

[9][21] This parent body population is confined to the narrow—about 1,000 km—and bright outer part of the main ring, and includes Metis and Adrastea.

[6] Images from the Galileo and New Horizons space probes show the presence of two sets of spiraling vertical corrugations in the main ring.

These waves became more tightly wound over time at the rate expected for differential nodal regression in Jupiter's gravity field.

The true vertical extent of the halo is not known but the presence of its material was detected as high as 10000 km over the ring plane.

[16] The optical properties of the halo ring can be explained by the hypothesis that it comprises only dust with particle sizes less than 15 μm.

[5][9] The large thickness of the halo can be attributed to the excitation of orbital inclinations and eccentricities of dust particles by the electromagnetic forces in the Jovian magnetosphere.

[21] The thickness of the gossamer rings is determined by vertical excursions of the moons due to their nonzero orbital inclinations.

[33] The same forces can explain a dip in the particle distribution and ring's brightness, which occurs between the orbits of Amalthea and Thebe.

This discovery implies that there are two particle populations in the gossamer rings: one slowly drifts in the direction of Jupiter as described above, while another remains near a source moon trapped in 1:1 resonance with it.

[5] The superior quality of the images obtained by the Galileo orbiter between 1995 and 2003 greatly extended the existing knowledge about the Jovian rings.

[2] Ground-based observation of the rings by the Keck[4] telescope in 1997 and 2002 and the HST in 1999[3] revealed the rich structure visible in back-scattered light.

Images transmitted by the New Horizons spacecraft in February–March 2007[13] allowed observation of the fine structure in the main ring for the first time.

In 2000, the Cassini spacecraft en route to Saturn conducted extensive observations of the Jovian ring system.