Amargasaurus

Amargasaurus (/əˌmɑːrɡəˈsɔːrəs/; "La Amarga lizard") is a genus of sauropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous epoch (129.4–122.46 mya) of what is now Argentina.

Amargasaurus was discovered in sedimentary rocks of the La Amarga Formation, which dates back to the Barremian and Aptian stages of the Early Cretaceous.

Amargasaurus probably fed at mid-height, as shown by the orientation of its inner ear and the articulation of its neck vertebrae, which suggest a habitual position of the snout 80 centimeters (31 inches) above the ground and a maximum height of 2.7 meters (8.9 feet).

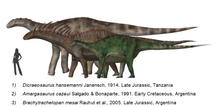

Within the Sauropoda, Amargasaurus is classified as a member of the family Dicraeosauridae, which differs from other sauropods in showing shorter necks and smaller body sizes.

[1][2][3]: 304 [4] It followed the typical sauropod body plan, with a long tail and neck, a small head, and a barrel-shaped trunk supported by four column-like legs.

[7] The most striking features of the skeleton were the extremely tall, upwardly projecting neural spines on the neck and anterior dorsal vertebrae.

[8] The last two dorsal vertebrae, the hip, and the foremost tail in Amargasaurus also had elongated spines; these were not bifurcated but flared into a paddle-shaped upper end.

[12][13] Skull features shared with Dicraeosaurus but absent in most other sauropods included the fused frontal bones and the notably long basipterygoid processes, bony extensions connecting the braincase with the palate.

[11] The only known skeleton (specimen number MACN-N 15) was discovered in February 1984 by Guillermo Rougier during an expedition led by Argentine paleontologist José Bonaparte.

[15] The discovery site is located in the La Amarga arroyo in the Picún Leufú Department of Neuquén Province in northern Patagonia, 70 kilometers (43 miles) south of Zapala.

[7] The first, unofficial, mention of Amargasaurus as a new genus of dinosaur was published by Bonaparte in the 1984 Italian book Sulle Orme dei Dinosauri.

In 1983, Cazau informed Bonaparte's team about the paleontological significance of the La Amarga Formation, leading to the discovery of the skeleton.

[20]: 17 [8][19] A 2015 analysis by Tschopp and colleagues came to the preliminary result that two poorly known genera from the Morrison Formation, Dyslocosaurus polyonychius and Dystrophaeus viaemalae, might be additional members of the Dicraeosauridae.

[10] The following cladogram by Gallina and colleagues (2019)[8] shows the presumed relationships between members of the Dicraeosauridae: Rebbachisauridae Diplodocidae Suuwassea Lingwulong Bajadasaurus Pilmatueia Amargasaurus Dicraeosaurus Brachytrachelopan Both the function and the appearance in life of the extremely elongated and bifurcated vertebral spines remain elusive.

[9] Daniela Schwarz and colleagues, in 2007, concluded that the bifurcated neural spines of diplodocids and dicraeosaurids enclosed an air sac, which would have been connected to the lungs as part of the respiratory system.

In Dicraeosaurus, this air sac (the so-called supravertebral diverticulum) would have rested on top of the neural arch and filled the entire space between the spines.

A cover of either keratin or skin is indicated striations on the surface of the spines similar to those of bony horn cores of today's bovids.

[25] In 2016, Mark Hallett and Mathew Wedel suggested that the backwards-directed spines might have been able to skewer predators when the neck was abruptly drawn backwards during an attack.

A similar defense strategy is found in today's giant sable antelope and Arabian oryx, which can use their long, backwards directed horns to stab attacking lions.

[26] Pablo Gallina and colleagues (2019) described the closely related Bajadasaurus, which had neural spines similar to those of Amargasaurus, and suggested that both genera employed them for defense.

A defense function would have been especially effective in Bajadasaurus as the spines were directed forwards and would have reached past the tip of the snout, deterring predators.

[27] Paulina Carabajal and colleagues, in 2014, CT-scanned the skull, allowing for the generation of three-dimensional models of both the cranial endocast (the cast of the brain cavity) and the inner ear.

Raising of the neck, e.g. for reaching an alert position, would have been constricted by the elongated neural spines, not permitting heights greater than 270 cm (8.9 ft).

[7] Salgado and Bonaparte, in 1991, suggested that Amargasaurus was a slow walker, as both the forearms and lower legs were proportionally short, as a feature common to slow-moving animals.

During locomotion, leg bones are strongly affected by bending moments, representing a limiting factor for the maximum speed of an animal.

The rib showed the most complete record of lines of arrested growth, indicating that the Amargasaurus holotype individual was at least ten years old.

In the outer cortex (the most external layer of the bone when seen in cross section) of the Amargasaurus individual, lines of arrested growth are more abundant, indicating sexual maturity.

[30] Amargasaurus stems from sedimentary rocks of the La Amarga Formation, which is part of the Neuquén Basin and dates to the Barremian and late Aptian of the Early Cretaceous.

Most vertebrate fossils, including Amargasaurus, have been found in the lowermost (oldest) part of the formation, the Puesto Antigual Member.