Ambisonics

This extra step allows the producer to think in terms of source directions rather than loudspeaker positions, and offers the listener a considerable degree of flexibility as to the layout and number of speakers used for playback.

With the widespread availability of powerful digital signal processing (as opposed to the expensive and error-prone analog circuitry that had to be used during its early years) and the successful market introduction of home theatre surround sound systems since the 1990s, interest in Ambisonics among recording engineers, sound designers, composers, media companies, broadcasters and researchers has returned and continues to increase.

In particular, it has proved an effective way to present spatial audio in Virtual Reality applications (e.g. YouTube 360 Video), as the B-Format scene can be rotated to match the user's head orientation, and then be decoded as binaural stereo.

Ambisonics can be understood as a three-dimensional extension of M/S (mid/side) stereo, adding additional difference channels for height and depth.

It positions the source at the desired angle by distributing the signal over the Ambisonic components with different gains: Being omnidirectional, the

The B-format components can be combined to derive virtual microphones with any first-order polar pattern (omnidirectional, cardioid, hypercardioid, figure-of-eight or anything in between) pointing in any direction.

Several such microphones with different parameters can be derived at the same time, to create coincident stereo pairs (such as a Blumlein) or surround arrays.

For perfectly regular layouts, a simplified decoder can be generated by pointing a virtual cardioid microphone in the direction of each speaker.

In practice, that translates to slightly blurry sources, but also to a comparably small usable listening area or sweet spot.

The resolution can be increased and the sweet spot enlarged by adding groups of more selective directional components to the B-format.

In practice, higher orders require more speakers for playback, but increase the spatial resolution and enlarge the area where the sound field is reproduced perfectly (up to an upper boundary frequency).

In this range, the only available information is the phase relationship between the two ear signals, called interaural time difference, or ITD.

Evaluating this time difference allows for precise localisation within a cone of confusion: the angle of incidence is unambiguous, but the ITD is the same for sounds from the front or from the back.

As long as the sound is not totally unknown to the subject, the confusion can usually be resolved by perceiving the timbral front-back variations caused by the ear flaps (or pinnae).

Fortunately, the head will create a significant acoustic shadow in this range, which causes a slight difference in level between the ears.

Gerzon has shown that the quality of localisation cues in the reproduced sound field corresponds to two objective metrics: the length of the particle velocity vector

Gerzon and Barton (1992) define a decoder for horizontal surround to be Ambisonic if In practice, satisfactory results are achieved at moderate orders even for very large listening areas.

Much of this ability is due to the shape of the head (especially the pinna) producing a variable frequency response depending on the angle of the source.

True Ambisonics decoding however requires spatial equalisation of the signals to account for the differences in the high- and low-frequency sound localisation mechanisms in human hearing.

The obvious advantage of pre-decoding is that any surround listener can be able to experience Ambisonics; no special hardware is required beyond that found in a common home theatre system.

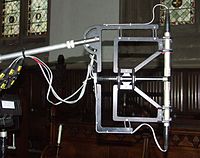

[17] Ambisonic content can be created in two basic ways: by recording a sound with a suitable first- or higher-order microphone, or by taking separate monophonic sources and panning them to the desired positions.

)[citation needed] Native arrays are most commonly used for horizontal-only surround, because of increasing positional errors and shading effects when adding a fourth microphone.

Since it is impossible to build a perfectly coincident microphone array, the next-best approach is to minimize and distribute the positional error as uniformly as possible.

[25] A recent paper by Peter Craven et al.[26] (subsequently patented) describes the use of bi-directional capsules for higher order microphones to reduce the extremity of the equalisation involved.

More sophisticated panners will additionally provide a radius parameter that will take care of distance-dependent attenuation and bass boost due to near-field effect.

However, due to arbitrary bus width restrictions, few professional digital audio workstations (DAW) support orders higher than second.

While traditional first-order B-format is well-defined and universally understood, there are conflicting conventions for higher-order Ambisonics, differing both in channel order and weighting, which might need to be supported for some time.

Reduction of redundancy among channels is desired, not only to enhance compression, but also to reduce the risk of dicernable phase errors.

)[35] As with mid-side joint stereo encoding, a static matrixing scheme (as in Opus) is usable for first-order ambisonics, but not optimal in case of multiple sources.

12 Since its adoption by Google and other manufacturers as the audio format of choice for virtual reality, Ambisonics has seen a surge of interest.