Ambohimanga

The significance of historical events here and the presence of royal tombs have given the hill a sacred character that is further enhanced at Ambohimanga by the burial sites of several Vazimba, the island's earliest inhabitants.

The gateways and construction of buildings within the compound are arranged according to two overlaid cosmological systems that value the four cardinal points radiating from a unifying center, and attach sacred importance to the northeastern direction.

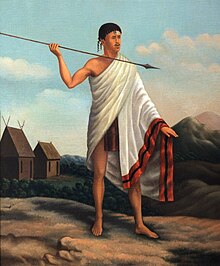

[4] By the 15th century the Merina ethnic group from the southeastern coast had gradually migrated into the central highlands[5] where they established hilltop villages interspersed among the existing Vazimba settlements, which were ruled by local kings.

[7] In the mid-16th century the disparate Merina principalities were united as the Kingdom of Imerina under the rule of King Andriamanelo (1540–1575), who initiated military campaigns to expel or assimilate the Vazimba population.

[11] According to oral history, however, the first to settle the site of the Ambohimanga rova was Andriamborona,[2] the dethroned prince of the highland territory of Imamo, who relocated to the then-unpopulated hilltop in around 1700 accompanied by his nephew, his wife, and his mother, Ratompobe.

Andriamborona and his family agreed to shift three times to different parts of the hill, including the future site of the royal compound of Bevato, in response to consecutive requests from the king.

Andriantsimitoviaminiandriana spent much of his reign strengthening the authority of his governance at Ambohimanga and attracting residents to settle in the surrounding villages while battling his brothers to increase the land under his control.

Andriambelomasina significantly expanded Ambohimanga and strengthened its defenses, enabling him to successfully repel an attack against the rova by a band of Sakalava warriors employed by his chief rival, the ruler of Antananarivo.

[16] Subsequent queens made their own mark on the site, including the reconstruction of Nanjakana by Rasoherina, and Ranavalona II's addition of two large pavilions to the Mahandrihono compound that reflected a syncretism of traditional and Western architectural styles.

This status remained until 1897 when the French colonial administration transferred all the relics and significant belongings of the royal family from Ambohimanga to Antananarivo to break the spirit of resistance and ethnic identity that these symbols inspired in the Malagasy people, particularly in the highlands.

[19] The terraced rice paddies that cover the hillsides to the north and south of the royal city were created in the 17th and 18th centuries to provide a staple food source to the inhabitants of the hill and its surrounding villages.

[12] The settlement was expanded by the construction of trenches bordering a second adjoining space to the northeast with two additional access points named Ampanidinamporona[12] and Ambavahaditsiombiomby, the latter a natural gateway formed by two boulders.

In addition to the inner seven gateways constructed by Andriantsimitoviaminiandriana in the early 18th century, there exists an exterior wall and second set of seven gates that were built before 1794[10] during the reign of Andrianampoinimerina, an act that symbolically marked the completion of the king's reunification of Imerina.

Every morning and evening, a team of twenty soldiers would work together to roll into place an enormous stone disk, 4.5 meters in diameter and 30 cm thick, weighing about 12 tons, to open or seal off the doorway.

[12] A series of ancestral fady (taboos) decreed by Andrianampoinimerina continue to apply in the village,[2] and include prohibitions against corn, pumpkins, pigs, onions, hedgehogs and snails; the use of reeds for cooking; and the cutting or collecting of wood from the sacred forests on the hill.

[12] Each of the three compounds built within the rova by successive Merina rulers bears distinct architectural styles that reflect the dramatic changes experienced in Imerina over the reign of the 19th century Kingdom of Madagascar, which saw the arrival and rapid expansion of European influence at the royal court.

The selection of specific wood and plant materials used in construction, each of which were imbued with distinct symbolic meaning, reflected traditional social norms and spiritual beliefs.

All buildings on the compound were destroyed by the French, who constructed a school on the site (Ecole Officiel), later followed by the Ambohimanga town hall (Tranompokonolona), which was razed after Madagascar regained independence.

[37] The figs that shade the esplanade are believed to be imbued with hasina enhanced by the bones and skulls of sacrificed zebu and special marking stones that pilgrims from across Madagascar, Mauritius, Reunion and Comoros have come to place around them.

Pilgrims gather in this courtyard to celebrate the Fandroana ceremony, during which time the sovereign historically engaged in a ritual bath to wash away the sins of the nation and restore order and harmony to society.

Mandraimanjaka was removed[12] and in its place Andrianampoinimerina built a house with a small tower,[36] which he named Manjakamiadana ("where it is good to rule"), designating it as the residence for the royal sampy (idol) called Imanjakatsiroa and the guardians assigned to protect it.

She demolished Manjakamiadana and in its place constructed two hybrid Malagasy-European pavilions using wood from the historic and spiritually significant Masoandro house,[12] which had been removed from the royal compound of Antananarivo by Ranavalona I.

[2] In 2013, Andrianampoinimerina's original house, the reconstructed tombs,[26] and the two royal pavilions[36] are preserved in the compound, which also includes a watchtower, a pen for sacrificial zebu, and two pools constructed during the reign of Ranavalona I.

[26] The site is highly sacred: Queen Rasoherina and her successors often sat on the stepping stone at its threshold to address their audience,[12] and many pilgrims come here to connect with the spirits of Andrianampoinimerina and his ancestors.

[45] The rich collection of funerary objects enclosed within the tombs was also removed for display in the Manjakamiadana palace on the Antananarivo rova grounds, which the Colonial Authority transformed into an ethnological museum.

[47] In the popular view, the link between Ambohimanga and the ancestors (Andrianampoinimerina in particular) rendered the royal city an even more potent symbol and source of legitimate power than the capital of Antananarivo, which was seen as having become a locus of corrupt politics and deviance from ancestral tradition.

[15] To the north of the compound is a stone esplanade that offers a clear view of the surrounding areas where Andrianampoinimerina reportedly came to reflect on his military strategy for bringing Imerina under his control.

In addition to helping replant the Ambohimanga woodlands, Mamelomaso has contributed to the restoration of the stones around the source of the spring, erected informational plaques around the hill, and paved a number of footpaths within the site.

The significance attached to the site in Imerina increased further when its sister rova in Antananarivo was destroyed by fire in 1995, contributing to a sense that Ambohimanga was the last remaining physical link to this sanctified past.

The rapidly growing but relatively impoverished population around Ambohimanga occasionally engages in illegal harvesting of plants and trees from the surrounding forests, threatening the integrity of the natural environment.