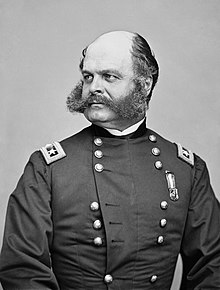

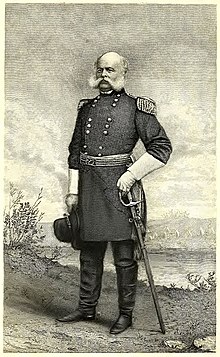

Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everts Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three-time Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor and industrialist.

He was responsible for some of the earliest victories in the Eastern theater, but was then promoted above his abilities, and is mainly remembered for two disastrous defeats, at Fredericksburg and the Battle of the Crater (Petersburg).

Ambrose attended Liberty Seminary as a young boy, but his education was interrupted when his mother died in 1841; he was apprenticed to a local tailor, eventually becoming a partner in the business.

President Buchanan's Secretary of War John B. Floyd contracted the Burnside Arms Company to equip a large portion of the Army with his carbine, mostly cavalry and induced him to establish extensive factories for its manufacture.

[6] Burnside commanded the Coast Division or North Carolina Expeditionary Force from September 1861 until July 1862, three brigades assembled in Annapolis, Maryland, which formed the nucleus for his future IX Corps.

He conducted a successful amphibious campaign that closed more than 80% of the North Carolina sea coast to Confederate shipping for the remainder of the war.

The result was a Union victory, with Elizabeth City and its nearby waters in their possession and the Confederate fleet captured, sunk, or dispersed.

[11] Burnside was promoted to major general of volunteers on March 18, 1862, in recognition of his successes at the battles of Roanoke Island and New Bern, the first significant Union victories in the Eastern Theater.

He received telegrams at this time from Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter which were extremely critical of Pope's abilities as a commander, and he forwarded on to his superiors in concurrence.

Burnside implicitly refused to give up his authority and acted as though the corps commander was first Maj. Gen. Jesse L. Reno (killed at South Mountain) and then Brig.

This cumbersome arrangement contributed to his slowness in attacking and crossing what is now called Burnside's Bridge on the southern flank of the Union line.

[15] Burnside did not perform an adequate reconnaissance of the area, and he did not take advantage of several easy fording sites out of range of the enemy; his troops were forced into repeated assaults across the narrow bridge, which was dominated by Confederate sharpshooters on the high ground.

He further increased the pressure by sending his inspector general to confront Burnside, who reacted indignantly: "McClellan appears to think I am not trying my best to carry this bridge; you are the third or fourth one who has been to me this morning with similar orders.

"[16] The IX Corps eventually broke through, but the delay allowed Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill's Confederate division to come up from Harpers Ferry and repulse the Union breakthrough.

Burnside assumed charge of the Army of the Potomac in a change of command ceremony at the farm of Julia Claggett in New Baltimore, Virginia.

"[21][18] President Abraham Lincoln pressured Burnside to take aggressive action and approved his plan on November 14 to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia.

His advance upon Fredericksburg was rapid, but the attack was delayed when the engineers were slow to marshal pontoon bridges for crossing the Rappahannock River, as well as his own reluctance to deploy portions of his army across fording points.

[22] In January 1863, Burnside launched a second offensive against Lee, but it bogged down in winter rains before anything was accomplished, and has derisively been called the Mud March.

Burnside had dispatched several agents to the rally who took down notes and brought back their "evidence" to the general, who then declared that it was sufficient grounds to arrest Vallandigham for treason.

38 which declared that offenders would be banished to enemy lines and finally decided that it was a good idea so Vallandigham was freed from jail and sent to Confederate hands.

Troops under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman marched to Burnside's aid, but the siege had already been lifted; Longstreet withdrew, eventually returning to Virginia.

This cumbersome arrangement was rectified on May 24 just before the Battle of North Anna, when Burnside agreed to waive his precedence of rank and was placed under Meade's direct command.

[29] As the two armies faced the stalemate of trench warfare at Petersburg in July 1864, Burnside agreed to a plan suggested by a regiment of former coal miners in his corps, the 48th Pennsylvania: to dig a mine under a fort named Elliot's Salient in the Confederate entrenchments and ignite explosives there to achieve a surprise breakthrough.

in the end his forces suffered 3,800 casualties [31][32] As a result of the Crater fiasco, Burnside was relieved of command on August 14 and sent on "extended leave" by Grant.

Burnside continued his association with the Republican Party, playing a prominent role in military affairs as well as serving as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee in 1881.

[39] Burnside died suddenly of "neuralgia of the heart" (Angina pectoris) on the morning of September 13, 1881, at his home in Bristol, Rhode Island, accompanied only by his doctor and family servants.

[41][42][39] Businesses and mills were closed for much of the day, and "thousands" of mourners from "all towns of the state and many places in Massachusetts and Connecticut" crowded the streets of Providence for the occasion.

Jeffry D. Wert described Burnside's relief after Fredericksburg in a passage that sums up his military career:[44] He had been the most unfortunate commander of the Army, a general who had been cursed by succeeding its most popular leader and a man who believed he was unfit for the post.

One reason might have been that, with all his deficiencies, Burnside never had any angles of his own to play; he was a simple, honest, loyal soldier, doing his best even if that best was not very good, never scheming or conniving or backbiting.

He customarily wore a high, bell-crowned felt hat with the brim turned down and a double-breasted, knee-length frock coat, belted at the waist—a costume which, unfortunately, is apt to strike the modern eye as being very much like that of a beefy city cop of the 1880s.Burnside was noted for his unusual beard, joining strips of hair in front of his ears to his mustache but with the chin clean-shaven; the word burnsides was coined to describe this style.