American Colonization Society

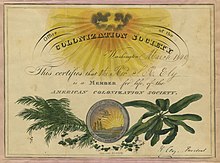

The American Colonization Society (ACS), initially the Society for the Colonization of Free People of Color of America, was an American organization founded in 1816 by Robert Finley to encourage and support the repatriation of freeborn people of color and emancipated slaves to the continent of Africa.

[8][9] According to historian Marc Leepson, "Colonization proved to be a giant failure, doing nothing to stem the forces that brought the nation to Civil War.

Few states extended citizenship rights to free black people prior to the 1860s and the Federal government, largely controlled by Slave Power, never showed any inclination to challenge the racial status quo.

[27] The ACS had its origins in 1816, when Charles Fenton Mercer, a Federalist member of the Virginia General Assembly, discovered accounts of earlier legislative debates on black colonization in the wake of Gabriel Prosser's rebellion.

Finley meant to colonize "(with their consent) the free people of color residing in our country, in Africa, or such other place as Congress may deem most expedient".

("Every attempt by the South to aid the Colonization Society, to send free colored people to Africa, enhances the value of the slave left on the soil".

[17][35] They wanted slaves to be free and believed Blacks would face better chances for freedom in Africa than in the United States, since they were not welcome in the South or North.

In 1819, they received $100,000 from Congress, and on February 6, 1820, the first ship, the Elizabeth, sailed from New York for West Africa with three white ACS agents and 86 African-American emigrants aboard.

[50] According to Benjamin Quarles, the colonization movement "originated abolitionism", by arousing the free Black people and other opponents of slavery.

[51] The following summary by Judge James Hall, editor of the Cincinnati-based Western Monthly Magazine, is from May 1834: The plan of colonizing free blacks, has been justly considered one of the noblest devices of Christian benevolence and enlightened patriotism, grand in its object, and most happily adapted to enlist the combined influence, and harmonious cooperation, of different classes of society.

It is a splendid conception, around which are gathered the hopes of the nation, the wishes of the patriot, the prayers of the Christian, and we trust, the approbation of Heaven.

[11] Black activist James Forten immediately rejected the ACS, writing in 1817 that "we have no wish to separate from our present homes for any purpose whatever".

He proposed instead Central and South America as "the ultimate destination and future home of the colored race on this continent" (see Linconia).

They recommended that if black people wish to leave the United States, they consider Canada or Mexico, where they would have civil rights and a climate that is similar to what they are accustomed to.

[60] William Lloyd Garrison began publication of his abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, in 1831, followed in 1832 by his Thoughts on African Colonization, which discredited the Society.

Garrison objected to the colonization scheme because rather than eliminating slavery, its key goal, as he saw it, was to remove free black people from America, thereby avoiding slave rebellions.

[65] In the second number of The Liberator, Garrison reprinted this commentary from the Boston Statesman, We were, however, rather surprised to see the proposal of sending the free negroes to Africa as returning them to their native land.

Let them admit him to more rights in the social world;—but unless they desire to be laughed at by all sincere and thinking men, they had better abandon the Quixotic plan of colonizing the Southern negroes at the cost of the North, until we can free our own borders from poverty, ignorance and distress.

[62]: 63 He claimed that the ACS had "ripened into the unmeasured calumniator of the abolitionist, ...the unblushing defender of the slaveholder, and the deadliest enemy of the colored race".

[68]In the meeting of forming British African Colonization Society held in London in July 1833, Nathaniel Paul, an abolitionist in support of William Lloyd Garrison's "Thoughts on African Colonization," argued that a significant number of opponents, including Black Americans in prominent cities of America, found inequality towards the Society because according to him, they were the ones who had remarkably contributed and fought to protect this country as their home through a historical period of generations.

[69] However, this Society was then trying to forcefully send them back to their ancestors' lands as, by that time, they were considered at risk for rebellion in the name of emancipation.

[69] From 1850 to 1858, according to Martin Delany, a supporter of African Americans' emigration from the United States to other regions, the creation of a republic was a significant movement to gain independence for the free Black people in America, in contrast to the ideology of staying and fighting for the equality of civil rights of Frederick Douglass.

Included were articles about Africa, lists of donors, letters of praise, information about emigrants, and official dispatches that espoused the prosperity and continued growth of the colony.

Biographer Stephen B. Oates has observed that Lincoln thought it immoral to ask black soldiers to fight for the U.S. and then to remove them to Africa after their military service.

Others, such as the historian Michael Lind, believe that as late as 1864, Lincoln continued to hold out hope for colonization, noting that he allegedly asked Attorney General Edward Bates if the Reverend James Mitchell could stay on as "your assistant or aid in the matter of executing the several acts of Congress relating to the emigration or colonizing of the freed Blacks".

[82] By late into his first term as president, Lincoln had publicly abandoned the idea of colonization after speaking about it with Frederick Douglass,[83] who objected harshly to it.

[84] Colonizing proved expensive; under the leadership of Henry Clay the ACS spent many years unsuccessfully trying to persuade the U.S. Congress to fund emigration.

The Society, in its Thirty-fourth Annual Report, acclaimed the news as "a great Moral demonstration of the propriety and necessity of state action!

[90] In Liberia, the Society maintained offices at the junction of Ashmun and Buchanan Streets at the heart of Monrovia's commercial district, next to the True Whig Party headquarters in the Edward J. Roye Building.

[91] In the 1950s, racism was an increasingly important issue and by the late 1960s and 1970s, it had been forced to the forefront of public consciousness by the civil rights movement.