American airborne landings in Normandy

In mid-February Eisenhower received word from Headquarters U.S. Army Air Forces that the TO&E of the C-47 Skytrain groups would be increased from 52 to 64 aircraft (plus nine spares) by April 1 to meet his requirements.

On April 12 a route was approved that would depart England at Portland Bill, fly at low altitude southwest over water, then turn 90 degrees to the southeast and come in "by the back door" over the western coast.

Over the reluctance of the naval commanders, exit routes from the drop zones were changed to fly over Utah Beach, then northward in a 10 miles (16 km) wide "safety corridor", then northwest above Cherbourg.

The veteran 52nd Troop Carrier Wing (TCW), wedded to the 82nd Airborne, progressed rapidly and by the end of April had completed several successful night drops.

All matériel requested by commanders in IX TCC, including armor plating, had been received with the exception of self-sealing fuel tanks, which Chief of the Army Air Forces General Henry H. Arnold had personally rejected because of limited supplies.

For the troop carrier aircraft this was in the form of three white and two black stripes, each two feet (60 cm) wide, around the fuselage behind the exit doors and from front to back on the outer wings.

The 300 men of the pathfinder companies were organized into teams of 14-18 paratroops each, whose main responsibility would be to deploy the ground beacon of the Rebecca/Eureka transponding radar system, and set out holophane marking lights.

The paratroops trained at the school for two months with the troop carrier crews, but although every C-47 in IX TCC had a Rebecca interrogator installed, to keep from jamming the system with hundreds of signals, only flight leads were authorized to use it in the vicinity of the drop zones.

Despite many early failures in its employment, the Eureka-Rebecca system had been used with high accuracy in Italy in a night drop of the 82nd Airborne Division to reinforce the U.S. Fifth Army during the Salerno landings, codenamed Operation Avalanche, in September 1943.

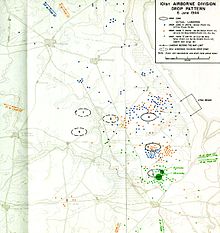

The teams assigned to mark DZ T northwest of Sainte-Mère-Église were the only ones dropped with accuracy, and while they deployed both Eureka and BUPS, they were unable to show lights because of the close proximity of German troops.

Each parachute infantry regiment (PIR), a unit of approximately 1800 men organized into three battalions, was transported by three or four serials, formations containing 36, 45, or 54 C-47s, and separated from each other by specific time intervals.

Weather over the channel was clear; all serials flew their routes precisely and in tight formation as they approached their initial points on the Cotentin coast, where they turned for their respective drop zones.

The negative impact of dropping at night was further illustrated when the same troop carrier groups flew a second lift later that day with precision and success under heavy fire.

The first flights, inbound to DZ A, were not surprised by the bad weather, but navigating errors and a lack of Eureka signal caused the 2nd Battalion 502nd PIR to come down on the wrong drop zone.

The 501st PIR's serial also encountered severe flak but still made an accurate jump on Drop Zone D. Part of the DZ was covered by pre-registered German fire that inflicted heavy casualties before many troops could get out of their chutes.

Pathfinders on DZ O turned on their Eureka beacons as the first 82nd serial crossed the initial point and lighted holophane markers on all three battalion assembly areas.

Estimates of drowning casualties vary from "a few"[8] to "scores"[9] (against an overall D-Day loss in the division of 156 killed in action), but much equipment was lost and the troops had difficulty assembling.

It arrived at 20:53, seven minutes early, coming in over Utah Beach to limit exposure to ground fire, into a landing zone clearly marked with yellow panels and green smoke.

German forces around Turqueville and Saint Côme-du-Mont, 2 miles (3.2 km) on either side of Landing Zone E, held their fire until the gliders were coming down, and while they inflicted some casualties, were too distant to cause much harm.

The last glider serial of 50 Wacos, hauling service troops, 81 mm mortars, and one company of the 401st, made a perfect group release and landed at LZ W with high accuracy and virtually no casualties.

All of these operations came in over Utah Beach but were nonetheless disrupted by small arms fire when they overflew German positions, and virtually none of the 101st's supplies reached the division.

On June 6, the German 6th Parachute Regiment (FJR6), commanded by Oberst Friedrich August von der Heydte,[13] (FJR6) advanced two battalions, I./FJR6 to Sainte-Marie-du-Mont and II./FJR6 to Sainte-Mère-Église, but faced with the overwhelming numbers of the two U.S. divisions, withdrew.

The 325th and 505th passed through the 90th Division, which had taken Pont l'Abbé (originally an 82nd objective), and drove west on the left flank of VII Corps to capture Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte on June 16.

Marshall's original data came from after-action interviews with paratroopers after their return to England in July 1944, which was also the basis of all U.S. Army histories on the campaign written after the war, and which he later incorporated in his own commercial book.

[21] Others critical included Max Hastings (Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy) and James Huston (Out of the Blue: U.S. Army Airborne Operations in World War II).

[4]The troop carrier pilots in their remembrances and histories admitted to many errors in the execution of the drops but denied the aspersions on their character, citing the many factors since enumerated and faulty planning assumptions.

[25] Wolfe noted that although his group had botched the delivery of some units in the night drop, it flew a second, daylight mission on D-Day and performed flawlessly although under heavy ground fire from alerted Germans.

Despite this, controversy did not flare until the assertions reached the general public as a commercial best-seller in Stephen Ambrose's Band of Brothers, particularly in sincere accusations by icons such as Richard Winters.

In 1995, following publication of D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II, troop carrier historians, including veterans Lew Johnston (314th TCG), Michael Ingrisano Jr. (316th TCG), and former U.S. Marine Corps airlift planner Randolph Hils, attempted to open a dialog with Ambrose to correct errors they cited in D-Day, which they then found had been repeated from the more popular and well-known Band of Brothers.

Their frustration with his failure to follow through on what they stated were promises to correct the record, particularly to the accusations of general cowardice and incompetence among the pilots, led them to detailed public rejoinders when the errors continued to be widely asserted, including in a History Channel broadcast April 8, 2001.