American anthropology

This slippage is a problem because during the formative years of modern primatology, some primatologists were trained in anthropology (and understood that culture refers to learned behavior among humans), and others were not.

[28] Tomasello emphasizes that this kind of imitative learning "relies fundamentally on infants' tendency to identify with adults, and on their ability to distinguish in the actions of others the underlying goal and the different means that might be used to achieve it.

"[30][31] He concludes that the key feature of cultural learning is that it occurs only when an individual "understands others as intentional agents, like the self, who have a perspective on the world that can be followed into, directed and shared.

"In general, for the vast majority of words in their language, children must find a way to learn in the ongoing flow of social interaction, sometimes from speech not even addressed to them.

"[41] In Holloway's view, our non-human ancestors, like those of modern chimpanzees and other primates, shared motor and sensory skills, curiosity, memory, and intelligence, with perhaps differences in degree.

Holloway concludes that the first instance of symbolic thought among humans provided a "kick-start" for brain development, tool complexity, social structure, and language to evolve through a constant dynamic of positive feedback.

[47] Once some useful behavior spreads within a population and becomes more important for subsistence, it will generate selection pressures on genetic traits that support its propagation ... Stone and symbolic tools, which were initially acquired with the aid of flexible ape-learning abilities, ultimately turned the tables on their users and forced them to adapt to a new niche opened by these technologies.

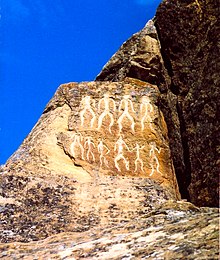

It is the diagnostic of Homo symbolicus.According to Deacon, this occurred between 2 and 2.5 million years ago, when we have the first fossil evidence of stone tool use and the beginning of a trend in an increase in brain size.

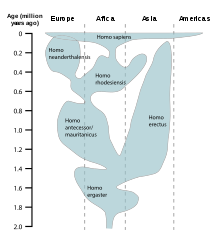

Given that the evolution of H. sapiens began with ancestors who did not yet have "culture," what led them to move away from cognitive, learning, communication, and tool-making strategies that were and continued to be adaptive for most other primates (and, some have suggested, most other species of animals)?

The special demands of acquiring meat and caring for infants in our own evolution together contribute to the underlying impetus for the third characteristic feature of human reproductive patterns: cooperative group living.What is uniquely characteristic about human societies is what required symbolic cognition, which consequently leads to the evolution of culture: "cooperative, mixed-sex social groups, with significant male care and provisioning of offspring, and relatively stable patterns of reproductive exclusion."

The first forms of symbolic thinking made stone tools possible, which in turn made hunting for meat a more dependable source of food for our nonhuman ancestors while making possible forms of social communication that make sharing between males and females, but also among males, decreasing sexual competition: So the socio-ecological problem posed by the transition to a meat-supplemented subsistence strategy is that it cannot be utilized without a social structure which guarantees unambiguous and exclusive mating and is sufficiently egalitarian to sustain cooperation via shared or parallel reproductive interests.

Instead, he "is committed to a fluid semiotic version of the traditional culture concept in which material items, artifacts, are full participants in the creation, deployment, alteration, and fading away of symbolic complexes.

Evolutionary anthropologist Robin I. Dunbar has proposed that language evolved as early humans began to live in large communities which required the use of complex communication to maintain social coherence.

Particularly the structural theory of Ferdinand de Saussure which describes symbolic systems as consisting of signs (a pairing of a particular form with a particular meaning) has come to be applied widely in the study of culture.

Linguists call different ways of speaking language varieties, a term that encompasses geographically or socioculturally defined dialects as well as the jargons or styles of subcultures.

Franz Boas's student Alfred Kroeber (1876–1970) identified culture with the "superorganic," that is, a domain with ordering principles and laws that could not be explained by or reduced to biology.

[94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101] Others, such as Ruth Benedict (1887–1948) and Margaret Mead (1901–1978), produced monographs or comparative studies analyzing the forms of creativity possible to individuals within specific cultural configurations.

"[109] Influenced by German historians Wilhelm Dilthey and Oswald Spengler, as well as by gestalt psychology, she argued that "the whole determines its parts, not only their relation but their very nature,"[110] and that "cultures, likewise, are more than the sum of their traits.

Benedict observed that many Westerners felt that this view forced them to abandon their "dreams of permanence and ideality and with the individual's illusions of autonomy" and that for many, this made existence "empty.

Although Boas argued that anthropologists had yet to collect enough solid evidence from a diverse sample of societies to make any valid general or universal claims about culture, by the 1940s some felt ready.

Whereas Kroeber and Benedict had argued that "culture"—which could refer to local, regional, or trans-regional scales—was in some way "patterned" or "configured," some anthropologists now felt that enough data had been collected to demonstrate that it often took highly structured forms.

Instead of making generalizations that applied to large numbers of societies, Lévi-Strauss sought to derive from concrete cases increasingly abstract models of human nature.

"[citation needed] In the United Kingdom, the creation of structural functionalism was anticipated by Raymond Firth's (1901–2002) We the Tikopia, published in 1936, and marked by the publication of African Political Systems, edited by Meyer Fortes (1906–1983) and E.E.

[124] Radcliffe-Brown rejected Malinowski's notion of function, and believed that a general theory of primitive social life could only be built up through the careful comparison of different societies.

In short, instead of culture (understood as all human non-genetic or extra-somatic phenomena) they made "sociality" (interactions and relationships among persons and groups of people) their object of study.

Culture, once extended to all acts and ideas employed in social life, was now relegated to the margins as "world view" or "values".Nevertheless, several of Talcott Parsons' students emerged as leading American anthropologists.

When disjunctures between these boundaries become highly salient, for example during the period of European de-colonization of Africa in the 1960s and 1970s, or during the post-Bretton Woods realignment of globalization, however, the difference often becomes central to anthropological debates.

In the 1940s and 1950s their students, most notably Marvin Harris, Sidney Mintz, Robert Murphy, Roy Rappaport, Marshall Sahlins, Elman Service, Andrew P. Vayda and Eric Wolf dominated American anthropology.

These comparative and practical perspectives, though not unique to formal anthropology, are specially husbanded there, and might well be impaired, if the study of man were to be united under the guidance of others who lose touch with experience in concern for methodology, who forget the ends of social knowledge in elaborating its means, or who are unwittingly or unconcernedly culture-bound.It is these elements, Hymes argued, that justify a "general study of man," that is, "anthropology".

[165] Joseph Jablow documented how Cheyenne social organization and subsistence strategy between 1795 and 1840 were determined by their position in trade networks linking Whites and other Indians.