History of American journalism

With the coming of digital journalism in the 21st Century, newspapers faced a business crisis as readers turned to social media for news and advertisers followed them to services such as Facebook.

The history of American journalism began in 1690, when Benjamin Harris published the first edition of "Public Occurrences, Both Foreign and Domestic" in Boston.

Harris had strong trans-Atlantic connections and intended to publish a regular weekly newspaper along the lines of those in London, but he did not get prior approval and his paper was suppressed after a single edition.

As the colonies grew rapidly in the 18th century, newspapers appeared in port cities along the East Coast, usually started by master printers seeking a sideline.

Pseudonymous publishing, a common practice of that time, protected writers from retribution from government officials and others they criticized, often to the point of what today would be considered libel.

[3] The owner acted as publisher, reporter, editor, typesetter, printer, and accountant, with perhaps one helper to assist with the several hundred copies printed every week.

The content included advertising of newly landed products, and local news items, usually based on commercial and political events.

The Tribune was the first newspaper, in 1886, to use the linotype machine, invented by Ottmar Mergenthaler, which rapidly increased the speed and accuracy with which type could be set.

Top publishers, such as Schuyler Colfax in 1868, Horace Greeley in 1872, Whitelaw Reid in 1892, Warren Harding in 1920 and James Cox also in 1920, were nominated on the national ticket.

Paid advertising was unnecessary, as the party encouraged all its loyal supporters to subscribe:[28] By the time of the Civil War, many moderately sized cities had at least two newspapers, often with very different political perspectives.

After the massive Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, angry mobs in the North destroyed substantial property owned by remaining secessionist newspapers.

[30] After 1900, William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer and other big city politician-publishers discovered they could make far more profit through advertising, at so many dollars per thousand readers.

There was less political news after 1900, apparently because citizens became more apathetic, and shared their partisan loyalties with the new professional sports teams that attracted growing audiences.

[31][32] Whitelaw Reid, the powerful long-time editor of the Republican New York Tribune, emphasized the importance of partisan newspapers in 1879: As the country and its inhabitants explored and settled further west the American landscape changed.

In order to supply these new pioneers of western territories with information, publishing was forced to expand past the major presses of Washington, D.C., and New York.

The public may have initially benefited as "muckraking" journalism exposed corruption, but its often excessively sensational coverage of a few juicy stories alienated many readers.

After noticing the White House reporters huddled outside in the rain one day, he gave them their own room inside, effectively inventing the presidential press briefing.

The grateful press, with unprecedented access to the White House, rewarded Roosevelt with intense favorable coverage; The nation's editorial cartoonists loved him even more.

[44] Journalism historians pay by far the most attention to the big city newspapers, largely ignoring small-town dailies and weeklies that proliferated and dealt heavily in local news.

He drew the line at expose-oriented scandal-mongering journalists who during his term set magazine subscriptions soaring with attacks on corrupt politicians, mayors, and corporations.

[55][56] Freedom of the press became well-established legal principle, although President Theodore Roosevelt tried to sue major papers for reporting corruption in the purchase of the Panama Canal rights.

Roosevelt had a more positive impact on journalism—he provided a steady stream of lively copy, making the White House the center of national reporting.

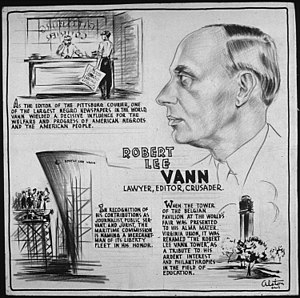

[57] Rampant discrimination against African-Americans did not prevent them from founding their own daily and weekly newspapers, especially in large cities, and these flourished because of the loyalty of their readers.

[58] Abolitionist Philip Alexander Bell (1808-1886) started the Colored American in New York City in 1837, then became co-editor of The Pacific Appeal and founder of The Elevator, both significant Reconstruction Era newspapers based in San Francisco.

[62] In states like Nebraska, founded on large immigrants populations, where many residents moved from Czechoslovakia, Germany and Denmark foreign-language papers provided a place for these people to make cultural and economic contributions to their new country and home.

Today, Spanish language newspapers such as El Diario La Prensa (founded in 1913) exist in Hispanic strongholds, but their circulations are small.

[66] Following the emergence of browsers, USA Today became the first newspaper to offer an online version of its publication in 1995, though CNN launched its own site later that year.

[67] Especially after 2000, the Internet brought free news and classified advertising to audiences that no longer saw a reason for subscriptions, undercutting the business model of many daily newspapers.

Bankruptcy loomed across the U.S. and did hit such major papers as the Rocky Mountain News (Denver), the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times, among many others.

Jane Chapman and Nick Nuttall find that proposed solutions, such as multiplatforms, paywalls, PR-dominated news gathering, and shrinking staffs have not resolved the challenge.