American marten

Populations have rebounded since, with them being considered a species of least-concern by the IUCN; however, they remain extirpated from some areas of the Northeast, and of the seven subspecies, one is threatened.

The Pacific marten (Martes caurina) was formerly thought to be conspecific, but genetic studies support it being a distinct species from M.

[11] A fossil species (originating from the Late Pleistocene to Early Holocene) known as Martes nobilis is considered synonymous with M.

From east to west, its distribution extends from Newfoundland to western Alaska, and southwest to the Pacific coast of Canada.

In the northeastern and midwestern United States, American marten distribution is limited to mountain ranges that provide preferred habitats.

A broad, natural hybrid zone between the Pacific and American martens is known to exist in the Columbia Mountains, as well as Kupreanof and Kuiu Islands in Alaska.

[12] Home range size of the American marten is extremely variable, with differences attributable to sex,[24][25][26][27] year, geographic area,[12] prey availability,[12][28] cover type, quality or availability,[12][28] habitat fragmentation,[29] reproductive status, resident status, predation,[30] and population density.

American marten male pelts often show signs of scarring on the head and shoulders, suggesting intrasexual aggression that may be related to home range maintenance.

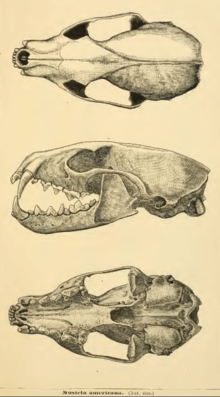

[34] The American marten is a long, slender-bodied weasel about the size of a mink with relatively large, rounded ears, short limbs, and a bushy tail.

Their long, silky fur ranges in color from pale yellowish buff to tawny brown to almost black.

American marten usually have a characteristic throat and chest bib ranging in color from pale straw to vivid orange.

In south-central Alaska, American marten were nocturnal in autumn, with strong individual variability in diel activity in late winter.

One marten in south-central Alaska repeatedly traveled 7 to 9 miles (11–14 km) overnight to move between two areas of home range focal activity.

[26] One individual in central Idaho moved as much as 9 miles (14 km) a day in winter, but movements were largely confined to a 1,280-acre (518 ha) area.

[34] A snowy habitat in many parts of the range of the American marten provides thermal protection[33] and opportunities for foraging and resting.

On the Kenai Peninsula, individuals navigated through deep snow regardless of depth, with tracks rarely sinking >2 inches (5 cm) into the snowpack.

Snowfall patterns may affect distribution, with the presence of American marten linked to deep snow areas.

[12] American marten females use a variety of structures for natal and maternal denning, including the branches, cavities or broken tops of live trees, snags,[32] stumps, logs,[32] woody debris piles, rock piles, and red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) nests or middens.

[12] The timing of juvenile dispersal is not consistent throughout American marten's distribution, ranging from early August to October.

American marten are opportunistic predators, influenced by local and seasonal abundance and availability of potential prey.

Deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus), shrews (Soricidae), birds, and carrion are generally eaten less than expected, but may be important food items in areas lacking alternative prey species.

One study from Chichagof Island, southeast Alaska, found that Alaska blueberry (Vaccinium alaskensis) and oval leaf huckleberry (V. ovalifolium) seeds had higher germination rates after passing through the gut of American marten compared to seeds that dropped from the parent plant.

[47] In a harvested population in east-central Alaska, annual adult survival rates ranged from 0.51 to 0.83 over 3 years of study.

[27] Throughout the distribution of American marten, other predators include the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), bobcat (Lynx rufus) Canada lynx (L. canadensis), mountain lion (Puma concolor),[13][41] fisher (Pekania pennanti), wolverine (Gulo gulo), grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis), American black bear (U. americanus), and grey wolf (C. lupus).

[34] The fur of the American marten is shiny and luxuriant, resembling that of the closely related sable (Martes zibellina).

At the turn of the twentieth century, the American marten population was depleted due to the fur trade.

Numerous protection measures and reintroduction efforts have allowed the population to increase, but deforestation is still a problem for the marten in much of its habitat.

[28] Trapping is a major source of American marten mortality in some populations[31][48] and may account for up to 90% of all deaths in some areas.

[13] American marten host several internal and external parasites, including helminths, fleas (Siphonaptera), and ticks (Ixodida).

[28] American marten in central Ontario carried both toxoplasmosis and Aleutian disease, but neither affliction was suspected to cause significant mortality.