Black-footed ferret

The oldest recorded fossil find originates from Cathedral Cave, White Pine County, Nevada, and dates back 750,000 to 950,000 years ago.

[16] It combines several physical features common in both members of the subgenus Gale (least and short-tailed weasels) and Putorius (European and steppe polecats).

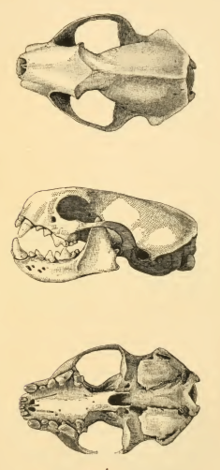

Its skull resembles that of polecats in its size, massiveness and the development of its ridges and depressions, though it is distinguished by the extreme degree of constriction behind the orbits where the width of the cranium is much less than that of the muzzle.

Although similar in size to polecats, its attenuate body, long neck, very short legs, slim tail, large orbicular ears and close-set pelage is much closer in conformation to weasels and stoats.

[15] The only noticeable differences between the black-footed ferret and the steppe polecat are the former's much shorter and coarser fur, larger ears, and longer post molar extension of the palate.

[19] Captive-bred ferrets used for the reintroduction projects were found to be smaller than their wild counterparts, though these animals rapidly attained historical body sizes once released.

The area midway between the front and back legs is marked by a large patch of dark umber-brown, which fades into the buffy surrounding parts.

[7] Snow-tracking from December to March over a 4-year period near Meeteetse, Wyoming, revealed that movement distances were shortest during winter and longest between February and April, when black-footed ferrets were breeding and white-tailed prairie dogs emerged from hibernation.

[7] From December to March over a 4-year study period, black-footed ferrets investigated 68 white-tailed prairie dog holes per 1 mile (1.6 km) of travel/night.

Potential prey items included thirteen-lined ground squirrels, plains pocket gophers, mountain cottontails, upland sandpipers, horned larks, and western meadowlarks.

[15] As of 2007[update], the only known wild black-footed ferret population was located on approximately 6,000 acres (2,400 hectares) in the western Big Horn Basin near Meeteetse, Wyoming.

[7] Primary causes of mortality include habitat loss, human-introduced diseases, and indirect poisoning from prairie dog control measures.

They are fatally susceptible to canine distemper virus,[15][24] introduced by striped skunks, common raccoons, red foxes, coyotes, and American badgers.

They can directly contract sylvatic plague (Yersinia pestis), and epidemics in prairie dog towns may completely destroy the ferrets' prey base.

[8] Native American tribes, including the Crow, Blackfoot, Sioux, Cheyenne, and Pawnee, used black-footed ferrets for religious rites and for food.

It feeds on birds, small reptiles and animals, eggs, and various insects, and is a bold and cunning foe to the rabbits, hares, grouse, and other game of our western regions.For a time, the black-footed ferret was harvested for the fur trade, with the American Fur Company having received 86 ferret skins from Pratt, Chouteau, and Company of St. Louis in the late 1830s.

[31] Sylvatic plague, a disease caused by Yersinia pestis introduced into North America, also contributed to the prairie dog die-off, though ferret numbers declined proportionately more than their prey, thus indicating other factors may have been responsible.

[33] Inbreeding depression may have also contributed to the decline, as studies on black-footed ferrets from Meeteetse, Wyoming, revealed low levels of genetic variation.

As such, this sole endemic North American ferret allows examining the impact of a severe genetic restriction on subsequent biological form and function, especially on reproductive traits and success.

Fish and Wildlife Service, state and tribal agencies, private landowners, conservation groups, and North American zoos have actively reintroduced ferrets back into the wild since 1991.

Beginning in Shirley Basin[37] in Eastern Wyoming, reintroduction expanded to Montana, six sites in South Dakota in 1994, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Saskatchewan, Canada and Chihuahua, Mexico.

[39] A population of 35 animals was released into Grasslands National Park in southern Saskatchewan on October 2, 2009,[40] and a litter of newborn kits was observed in July 2010.

An August 2007 report in the journal Science counted a population of 223 in one area of Wyoming (the original number of reintroduced ferrets, most of which died, was 228), and an annual growth rate of 35% from 2003 to 2006 was estimated.

[43][44] This rate of recovery is much faster than for many endangered species, and the ferret seems to have prevailed over the previous problems of disease and prey shortage that hampered its improvement.

[46] These wild populations are possible due to the extensive breeding program that releases surplus animals to reintroduction sites, which are then monitored by USFWS biologists for health and growth.

However, the species cannot depend just on ex situ breeding for future survival, as reproductive traits such as pregnancy rate and normal sperm motility and morphology have been steadily declining with time in captivity.

In 2005, the U.S. Forest Service began poisoning prairie dogs in private land buffer zones of the Conata Basin of Buffalo Gap National Grassland.

Following exposure by conservation groups including the Climate, Community & Biodiversity Alliance and national media[50] public outcry and a lawsuit mobilized federal officials, and the poisoning plan was revoked.

[54] In October 2022,[55] Elizabeth Ann received a hysterectomy due to health complications related to hydrometra, a condition causing excessive fluid retention within the uterus, alongside an underdeveloped uterine horn.

[57] In 2023, the black-footed ferret was featured on a United States Postal Service Forever stamp as part of the Endangered Species set, based on a photograph from Joel Sartore's Photo Ark.