Cupid and Psyche

The story's Neoplatonic elements and allusions to mystery religions accommodate multiple interpretations,[3] and it has been analyzed as an allegory and in light of folktale, Märchen or fairy tale, and myth.

Transformed into a donkey by magic gone wrong, Lucius undergoes various trials and adventures, and finally regains human form by eating roses sacred to Isis.

It occurs within a complex narrative frame, with Lucius recounting the tale as it in turn was told by an old woman to Charite, a bride kidnapped by pirates on her wedding day and held captive in a cave.

Exploring, she finds a marvelous house with golden columns, a carved ceiling of citrus wood and ivory, silver walls embossed with wild and domesticated animals, and jeweled mosaic floors.

When they see the splendor in which Psyche lives, they become envious, and undermine her happiness by prodding her to uncover her husband's true identity, since surely as foretold by the oracle she was lying with the vile winged serpent, who would devour her and her child.

One night after Cupid falls asleep, Psyche carries out the plan her sisters devised: she brings out a dagger and a lamp she had hidden in the room, in order to see and kill the monster.

[14] Psyche's only intention is to drown herself on the way, but instead she is saved by instructions from a divinely inspired reed, of the type used to make musical instruments, and gathers the wool caught on briers.

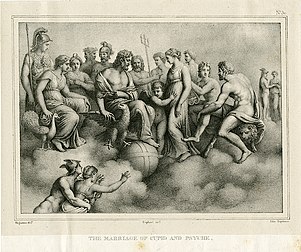

Zeus has Hermes convene an assembly of the gods in the theater of heaven, where he makes a public statement of approval, warns Venus to back off, and gives Psyche ambrosia, the drink of immortality,[16] so the couple can be united in marriage as equals.

Vulcan, the god of fire, cooks the food; the Horae ("Seasons" or "Hours") adorn, or more literally "empurple", everything with roses and other flowers; the Graces suffuse the setting with the scent of balsam, and the Muses with melodic singing.

As early as 1497, Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti made the banquet central to his description of a now-lost Cupid and Psyche cycle at the Villa Belriguardo, near Ferrara.

[23] The engraving in turn had been taken from Bartholomaeus Spranger's 1585 drawing of the same title, considered a "locus classicus of Dutch Mannerism" and discussed by Karel Van Mander for its exemplary composition involving numerous figures.

However, when he admits that "I [Cupid], the famed archer, wounded myself with my own weapon, and made you [Psyche] my wife" (V. 24), having cut himself on his own magic arrow (which induces passionate love for the first person the victim lays eyes on), the temptation for an allegorical interpretation of the story becomes somewhat complexified but not inherently contradictory or unsubstantiated.

The arrows of desire make it so that the victim cannot be satisfied with anyone except the sole target of their newfound affections; thus, Cupid's former predilections no longer occupy the same prominence they once held in his character, so that he changes from a wanton homewrecker to a devoted husband by the end of the narrative.

It was known to Latin writers such as Augustine of Hippo, Macrobius, Sidonius Apollinaris, Martianus Capella, and Fulgentius, but toward the end of the 6th century lapsed into obscurity and survived what was formerly known as the "Dark Ages" through perhaps a single manuscript.

[36] Boccaccio's text and interpretation of Cupid and Psyche in his Genealogia deorum gentilium (written in the 1370s and published 1472) was a major impetus to the reception of the tale in the Italian Renaissance and to its dissemination throughout Europe.

[41] Another peak of interest in Cupid and Psyche occurred in the Paris of the late 1790s and early 1800s, reflected in a proliferation of opera, ballet, Salon art, deluxe book editions, interior decoration such as clocks and wall paneling, and even hairstyles.

With his interest in natural philosophy, Darwin saw the butterfly as an apt emblem of the soul because it began as an earthbound caterpillar, "died" into the pupal stage, and was then resurrected as a beautiful winged creature.

William Morris retold the Cupid and Psyche story in verse in The Earthly Paradise (1868–70), and a chapter in Walter Pater's Marius the Epicurean (1885) was a prose translation.

[64] In a study published posthumously, Romanian folklorist Petru Caraman [ro] also argued for a folkloric origin, but was of the notion that Apuleius superimposed Graeco-Roman mythology on a pre-Christian myth about a serpentine or draconic husband, or a "King of Snakes" that becomes human at night.

Motifs from Apuleius occur in several fairy tales, including Cinderella and Rumpelstiltskin, in versions collected by folklorists trained in the classical tradition, such as Charles Perrault and the Grimm brothers.

In 1800, Ludwig Abeille premièred his four-act German opera (singspiel) Amor und Psyche, with a libretto by Franz Carl Hiemer [fr] based on Apuleius.

In the 19th century, Cupid and Psyche was a source for "transformations", visual interludes involving tableaux vivants, transparencies and stage machinery that were presented between the scenes of a pantomime but extraneous to the plot.

[74] Psyché et l'Amour was reproduced by the scenic painter Edouard von Kilanyi, who made a tour of Europe and the United States beginning in 1892,[75] and by George Gordon in an Australian production that began its run in December 1894.

Notable adaptations include: Viewed in terms of psychology rather than allegory, the tale of Cupid and Psyche shows how "a mutable person … matures within the social constructs of family and marriage".

[98][99] Cupid and Psyche has been analyzed from a feminist perspective as a paradigm of how the gender unity of women is disintegrated through rivalry and envy, replacing the bonds of sisterhood with an ideal of heterosexual love.

[108] The two are also depicted in high relief in mass-produced Roman domestic plaster wares from the 1st to 2nd centuries AD found in excavations at Greco-Bactrian merchant settlements on the ancient Silk Road at Begram in Afghanistan[109] (see gallery below).

The allegorical pairing depicts perfection of human love in integrated embrace of body and soul ('psyche' Greek for butterfly symbol for transcendent immortal life after death).

[6] A relief of Cupid and Psyche was displayed at the mithraeum of Capua, but it is unclear whether it expresses a Mithraic quest for salvation, or was simply a subject that appealed to an individual for other reasons.

[119] The most popular subjects for single paintings or sculpture are the couple alone, or explorations of the figure of Psyche, who is sometimes depicted in compositions that recall the sleeping Ariadne as she was found by Dionysus.

[121] Classical subject matter might be presented in terms of realistic nudity: in 1867, the female figure in the Cupid and Psyche of Alphonse Legros was criticized as a "commonplace naked young woman".