Amores (Ovid)

The book follows the popular model of the erotic elegy, as made famous by figures such as Tibullus or Propertius, but is often subversive and humorous with these tropes, exaggerating common motifs and devices to the point of absurdity.

[7] During the Augustan Era, boys attended schools that focused on rhetoric in order to prepare them for careers in politics and law.

[10] Under his rule, citizens were faithful to Augustus and the royal family, viewing them as "the embodiment of the Roman state.

"[9] This notion arose in part through Augustus' attempts to improve the lives of the common people by increasing access to sanitation, food, and entertainment.

[11] The arts, especially literature and sculpture, took on the role of helping to communicate and bolster this positive image of Augustus and his rule.

He then offers supporting evidence through his analysis of different kinds of beauty, before ending with a summary of his thesis in the final couplet.

[18] This logical flow usually connects one thought to next, and one poem to next, suggesting that Ovid was particularly concerned with the overall shape of his argument and how each part fit into his overall narrative.

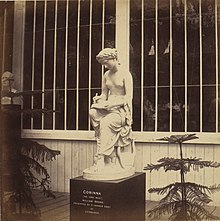

[22] Another place where this metaphor is exemplified when Ovid breaks down the heavily guarded door to reach his lover Corinna in II.12.

Amores I.1 begins with the same word as the Aeneid, "Arma" (an intentional comparison to the epic genre, which Ovid later mocks), as the poet describes his original intention: to write an epic poem in dactylic hexameter, "with material suiting the meter" (line 2), that is, war.

However, Cupid "steals one (metrical) foot" (unum suripuisse pedem, I.1 ln 4), turning it into elegiac couplets, the meter of love poetry.

[25][26] [27][28] While his predecessors and contemporaries took the love in the poetry rather seriously, Ovid spends much of his time playfully mocking their earnest pursuits.

This is best understood through the lens of humor and Ovid's playfulness, as to take it seriously would make the "fifty-six allusive lines...[look] absurdly pretentious if he meant a word of them.

[27] Other scholars through find sincerity in the humor, knowing that Ovid is playing a game based on rhetorical emphasis placed on Latin, and various styles poets and people adapted in Roman culture.

After his banishment in 8 AD, Augustus ordered Ovid's works removed from libraries and destroyed, but that seems to have had little effect on his popularity.

[33] The majority of Latin works have been lost, with very few texts rediscovered after the Dark Ages and preserved to the present day.

[35] Later in the 11th century, Ovid was the favourite poet of Abbot (and later Bishop) Baudry, who wrote imitation elegies to a nun – albeit about Platonic love.

[37] Wilkinson also credits Ovid with directly contributing around 200 lines to the classic courtly love tale Roman de la Rose.