Martial

In Book X of his Epigrams, composed between 95 and 98, he mentions celebrating his fifty-seventh birthday; hence he was born during March 38, 39, 40 or 41 AD (Mart.

His place of birth was Augusta Bilbilis (now Calatayud) in Hispania Tarraconensis, an information he gives by speaking of himself as "sprung from the Celts and Iberians, and a countryman of the Tagus".

In contrasting his own masculine appearance with that of an effeminate Greek, he draws particular attention to "his stiff Hispanian hair" (Mart.

His home was evidently one of rude comfort and plenty, sufficiently in the country to afford him the amusements of hunting and fishing, which he often recalls with keen pleasure, and sufficiently near the town to afford him the companionship of many comrades, the few survivors of whom he looks forward to meeting again after his thirty-four years' absence (Mart.

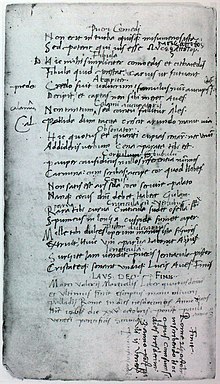

He published some juvenile poems of which he thought very little in his later years, and he chuckles at a foolish bookseller who would not allow them to die a natural death (Mart.

His faculty ripened with experience and with the knowledge of that social life which was both his theme and his inspiration; many of his best epigrams are among those written in his last years.

From many answers which he makes to the remonstrances of friends—among others to those of Quintilian—it may be inferred that he was urged to practice at the bar, but that he preferred his own lazy, some would say Bohemian kind of life.

Martial failed, however, in his application to Domitian for more substantial advantages, although he commemorates the glory of having been invited to dinner by him, and also the fact that he procured the privilege of citizenship for many persons on whose behalf he appealed to him.

The favour of the emperor procured him the countenance of some of the worst creatures at the imperial court—among them of the notorious Crispinus, and probably of Paris, the supposed author of Juvenal's exile, for whose monument Martial afterwards wrote a eulogistic epitaph.

He had a small villa and unproductive farm near Nomentum, in the Sabine territory, to which he occasionally retired from the pestilence, boors and noises of the city (Mart.

But the spell exercised over him by Rome and Roman society was too great; even the epigrams sent from Forum Corneli and the Aemilian Way ring much more of the Roman forum, and of the streets, baths, porticos, brothels, market stalls, public houses, and clubs of Rome, than of the places from which they are dated.

His final departure from Rome was motivated by a weariness of the burdens imposed on him by his social position, and apparently the difficulties of meeting the ordinary expenses of living in the metropolis (Mart.

The one consolation of his exile was a lady, Marcella, of whom he writes rather platonically as if she were his patroness—and it seems to have been a necessity of his life to always have a patron or patroness— rather than his wife or mistress.

Despite the two authors writing at the same time and having common friends, Martial and Statius are largely silent about one another, which may be explained by mutual dislike.

Martial in many places shows an undisguised contempt for the artificial kind of epic on which Statius's reputation chiefly rests; and it is possible that the respectable author of the Thebaid and the Silvae felt little admiration for the life or the works of the bohemian epigrammatist.

Pliny the Younger, in the short tribute which he pays to him on hearing of his death, wrote, "He had as much good-nature as wit and pungency in his writings".

[5] Martial professes to avoid personalities in his satire, and honour and sincerity (fides and simplicitas) seem to have been the qualities which he most admires in his friends.

Though many of his epigrams indicate a cynical disbelief in the female character, yet others prove that he could respect and almost revere a refined and courteous woman.

"[6] Martial makes this accusation in one of his epigrams: Tongilianus, you paid two hundred for your house; An accident too common in this city destroyed it.

Martial's epigrams are also characterized by their biting and often scathing sense of wit as well as for their lewdness; this has earned him a place in literary history as the original insult comic.

Below is a sample of his more insulting work: You feign youth, Laetinus, with your dyed hair So suddenly you are a raven, but just now you were a swan.

Or the following two examples (in translations by Mark Ynys-Mon): Fabullus' wife Bassa frequently totes A friend's baby, on which she loudly dotes.

The works of Martial became highly valued on their discovery by the Renaissance, whose writers often saw them as sharing an eye for the urban vices of their own times.

The poet's influence is seen in Juvenal, late classical literature, the Carolingian revival, the Renaissance in France and Italy, the Siglo de Oro, and early modern English and German poetry, until he became unfashionable with the growth of the Romantic movement.