An Incident at the Opera Ball on Mardi Gras in 1778

An Incident at the Opera Ball on Mardi Gras in 1778 was an affair that almost led to a serious duel within the Royal Family of France.

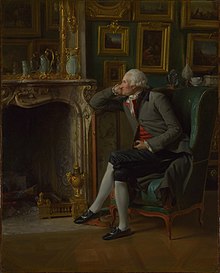

As a close confidant of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, he was, on the one hand, a mediator and advisor in this affair.

On the other hand, his residence in Paris, the Hôtel de Besenval, also played a role in this royal family dispute.

According to his own statements in his memoirs, the Baron de Besenval had written the report surrounding the events of the Incident at the Opera Ball on Mardi Gras in 1778 in that same year.

The Comte d'Artois and the Comtesse de Canillac noticed that they were being watched by the Duchesse de Bourbon, so they separated in the crowd at the ball in order to confuse the curious duchesse and to avoid an embarrassing situation that could have quickly escalated into a scandal.

She also considered it an affront that the Comte d'Artois had dared to take the comtesse with him to the ball after everything that had happened.

After exchanging a few words, during which the still masked Comte d'Artois apparently did not identify himself, the irritated duchesse tore the false beard from the duc's face with such violence that the straps with which the false beard was attached to the mask tore.

Enriched with lies and half-truths on the part of the duchesse, her story provoked the reaction she was looking for from her guests: Horror and indignation.

The king, for his part, entrusted the Ministre d'État, Jean-Frédéric Phélypeaux, Comte de Maurepas, with the matter, with the order to avoid a scandal.

The baron told the Comte d'Artois that the Duchesse de Bourbon had behaved in an absolutely reprehensible manner.

However, the Baron de Besenval also said that he, the Comte d'Artois, should not have allowed himself to be carried away by such impolite behaviour.

They participated enthusiastically in the conversation and all four laughed at the farce – although the matter was actually not amusing since the reputation of the royal family was at stake.

[8][9][10] Back in Paris, the Baron de Besenval noticed how the public mood in this affair was tilting to the detriment of the Comte d'Artois.

The Baron de Besenval suggested that the king must act now before things got out of hand and the reputation of the royal family was damaged.

The whole procedure was coordinated by the Ministre d'État, Jean-Frédéric Phélypeaux, Comte de Maurepas.

The Duc de Bourbon then wanted to speak, whereupon the king abruptly interrupted and unmistakably asked him to remain silent.

[13] On Sunday morning, 15 March, the Baron de Besenval took part in the Lever du Roi at the Château de Versailles when he noticed the queen's secretary, Pierre-Dominique Berthollet (1722–1791), called Campan, who made signs for him to follow him unobtrusively.

The first meeting failed because the two arrived too late at the agreed location and the queen had to attend the Holy Mass.

The parties involved remained hostile to each other and the outraged public thirsted for revenge in the form of a duel between the Duc de Bourbon and the Comte d'Artois.

This way you could kill two birds with one stone: On the one hand, the insult that the Duchesse de Bourbon had suffered from the Comte d'Artois could be atoned for.

The Comte d'Artois got off his horse and said to the Duc de Bourbon with a smile on his face: "Monsieur, the public claims that we are looking for each other."

The Duc de Bourbon also smiled, took off his hat and replied: "Monsieur, I am here to receive your orders.

They both took up their swords when the Duc de Bourbon said to the Comte d'Artois with a wink: "Don't go "en garde," Monsieur, when the sun blinds you."

[22] "I thought he [the Duc de Bourbon] was injured, and I went forward to ask the princes to suspend.

"Depending on the source of information, the Duc de Bourbon is said to have wounded the Comte d'Artois in the hand.

He brought the message to the Comte d'Artois that the queen wanted him to inform the king about what had happened.