Analytical engine

[4] The analytical engine incorporated an arithmetic logic unit, control flow in the form of conditional branching and loops, and integrated memory, making it the first design for a general-purpose computer that could be described in modern terms as Turing-Complete.

Construction of this machine was never completed; Babbage had conflicts with his chief engineer, Joseph Clement, and ultimately the British government withdrew its funding for the project.

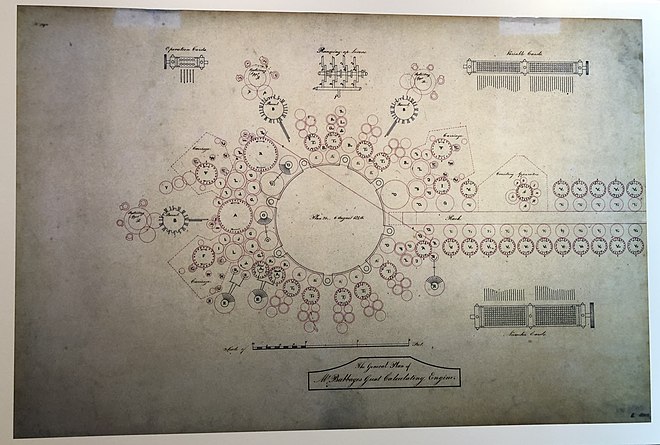

[16] Initially (1838) it was conceived as a difference engine curved back upon itself, in a generally circular layout, with the long store exiting off to one side.

[14][21] In 1842, the Italian mathematician Luigi Federico Menabrea published a description of the engine in French,[22] based on lectures Babbage gave when he visited Turin in 1840.

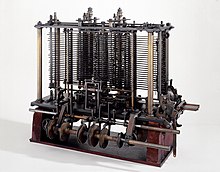

Late in his life, Babbage sought ways to build a simplified version of the machine, and assembled a small part of it before his death in 1871.

[1][7][24] In 1878, a committee of the British Association for the Advancement of Science described the analytical engine as "a marvel of mechanical ingenuity", but recommended against constructing it.

[27] Henry also proposed building a demonstration version of the full engine, with a smaller storage capacity: "perhaps for a first machine ten (columns) would do, with fifteen wheels in each".

[31] In October 2010, John Graham-Cumming started a "Plan 28" campaign to raise funds by "public subscription" to enable serious historical and academic study of Babbage's plans, with a view to then build and test a fully working virtual design which will then in turn enable construction of the physical analytical engine.

[35] By 2017, the "Plan 28" effort reported that a searchable database of all catalogued material was available, and an initial review of Babbage's voluminous Scribbling Books had been completed.

In the absence of other evidence I have had to adopt the minimal default assumption that both the operation and variable cards can only be turned backward as is necessary to implement the loops used in Babbage's sample programs.

[44] In his work Essays on Automatics (1914) Leonardo Torres Quevedo, inspired by Babbage, designed a theoretical electromechanical calculating machine which was to be controlled by a read-only program.

In the same year he started the Rapid Arithmetical Machine project to investigate the problems of constructing an electronic digital computer.

Howard Aiken, who built the quickly-obsoleted electromechanical calculator, the Harvard Mark I, between 1937 and 1945, praised Babbage's work likely as a way of enhancing his own stature, but knew nothing of the analytical engine's architecture during the construction of the Mark I, and considered his visit to the constructed portion of the analytical engine "the greatest disappointment of my life".

[51] J. Presper Eckert and John W. Mauchly similarly were not aware of the details of Babbage's analytical engine work prior to the completion of their design for the first electronic general-purpose computer, the ENIAC.

[54] By comparison the Harvard Mark I could perform the same task in just six seconds (though it is debatable that computer is Turing complete; the ENIAC, which is, would also have been faster).