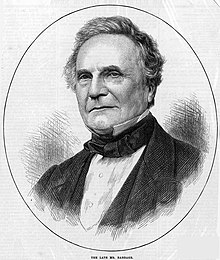

Charles Babbage

Babbage's birthplace is disputed, but according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography he was most likely born at 44 Crosby Row, Walworth Road, London, England.

[20] He was already self-taught in some parts of contemporary mathematics;[21] he had read Robert Woodhouse, Joseph Louis Lagrange, and Maria Gaetana Agnesi.

[31] Babbage purchased the actuarial tables of George Barrett, who died in 1821 leaving unpublished work, and surveyed the field in 1826 in Comparative View of the Various Institutions for the Assurance of Lives.

[25] In April 1828 he was in Rome, and relying on Herschel to manage the difference engine project, when he heard that he had become a professor at Cambridge, a position he had three times failed to obtain (in 1820, 1823 and 1826).

[38] These directions were closely connected with Babbage's ideas on computation, and in 1824 he won its Gold Medal, cited "for his invention of an engine for calculating mathematical and astronomical tables".

[42] The issue of the Nautical Almanac is now described as a legacy of a polarisation in British science caused by attitudes to Sir Joseph Banks, who had died in 1820.

[50] In the period to 1820 Babbage worked intensively on functional equations in general, and resisted both conventional finite differences and Arbogast's approach (in which Δ and D were related by the simple additive case of the exponential map).

[52] Babbage was out of sympathy with colleagues: George Biddell Airy, his predecessor as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Trinity College, Cambridge,[53] thought an issue should be made of his lack of interest in lecturing.

Simon Schaffer writes that his views of the 1830s included disestablishment of the Church of England, a broader political franchise, and inclusion of manufacturers as stakeholders.

It aimed to improve British science, and more particularly to oust Davies Gilbert as President of the Royal Society, which Babbage wished to reform.

[64] It was written out of pique, when Babbage hoped to become the junior secretary of the Royal Society, as Herschel was the senior, but failed because of his antagonism to Humphry Davy.

[74] From An essay on the general principles which regulate the application of machinery to manufactures and the mechanical arts (1827), which became the Encyclopædia Metropolitana article of 1829, Babbage developed the schematic classification of machines that, combined with discussion of factories, made up the first part of the book.

[83] He also pointed out that training or apprenticeship can be taken as fixed costs; but that returns to scale are available by his approach of standardisation of tasks, therefore again favouring the factory system.

[89] Babbage's theories are said to have influenced the layout of the 1851 Great Exhibition,[90] and his views had a strong effect on his contemporary George Julius Poulett Scrope.

[91] Karl Marx argued that the source of the productivity of the factory system was exactly the combination of the division of labour with machinery, building on Adam Smith, Babbage and Ure.

[95] George Holyoake saw Babbage's detailed discussion of profit sharing as substantive, in the tradition of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier, if requiring the attentions of a benevolent captain of industry, and ignored at the time.

[98] The French engineer and writer on industrial organisation Léon Lalanne was influenced by Babbage, but also by the economist Claude Lucien Bergery, in reducing the issues to "technology".

[111]Rejecting the Athanasian Creed as a "direct contradiction in terms", in his youth he looked to Samuel Clarke's works on religion, of which Being and Attributes of God (1704) exerted a particularly strong influence on him.

"[112] In his autobiography Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864), Babbage wrote a whole chapter on the topic of religion, where he identified three sources of divine knowledge:[113] He stated, on the basis of the design argument, that studying the works of nature had been the more appealing evidence, and the one which led him to actively profess the existence of God.

[114][115] Advocating for natural theology, he wrote: In the works of the Creator ever open to our examination, we possess a firm basis on which to raise the superstructure of an enlightened creed.

The testimony of man becomes fainter at every stage of transmission, whilst each new inquiry into the works of the Almighty gives to us more exalted views of his wisdom, his goodness, and his power.

[132][133] In 1838, Babbage invented the pilot (also called a cow-catcher), the metal frame attached to the front of locomotives that clears the tracks of obstacles;[134] he also constructed a dynamometer car.

The following quotation is typical: It is difficult to estimate the misery inflicted upon thousands of persons, and the absolute pecuniary penalty imposed upon multitudes of intellectual workers by the loss of their time, destroyed by organ-grinders and other similar nuisances.

[149] Babbage achieved a certain notoriety in this matter, being denounced in debate in Commons in 1864 for "commencing a crusade against the popular game of tip-cat and the trundling of hoops.

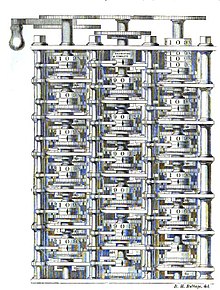

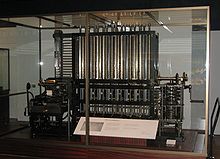

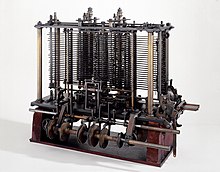

That they were not actually completed was largely because of funding problems and clashes of personality, most notably with George Biddell Airy, the Astronomer Royal.

Here, for the first time, mass production was applied to arithmetic, and Babbage was seized by the idea that the labours of the unskilled computers [people] could be taken over completely by machinery which would be quicker and more reliable.

[182] These modern versions of mechanical computation were highlighted in The Economist in its special "end of the millennium" black cover issue in an article entitled "Babbage's Last Laugh".

[185] On 25 July 1814, Babbage married Georgiana Whitmore, sister of British parliamentarian William Wolryche-Whitmore, at St. Michael's Church in Teignmouth, Devon.

[22] The couple lived at Dudmaston Hall,[186] Shropshire (where Babbage engineered the central heating system), before moving to 5 Devonshire Street, London in 1815.

[191] Babbage lived and worked for over 40 years at 1 Dorset Street, Marylebone, where he died, at the age of 79, on 18 October 1871; he was buried in London's Kensal Green Cemetery.