Anarchism in Japan

It existed throughout the 20th century in various forms, despite repression by the state that became particularly harsh during the two world wars, and it reached its height in the 1920s with organisations such as Kokuren and Zenkoku Jiren.

The next leading figure was Ōsugi Sakae, who involved himself heavily in support for anarcho-syndicalism and helped to bring the movement out of its 'winter period', until he was murdered by military police in 1923.

Another leading figure was Hatta Shūzō, who reoriented the anarchist movement in a more anarcho-communist direction during the late 1920s, opposing labour unions as a tool of revolution.

[1] He advocated what was described by Bowen Raddeker as "what we might call mutual aid", and he challenged the hierarchical relationships in Japanese society, including the hierarchy between the sexes.

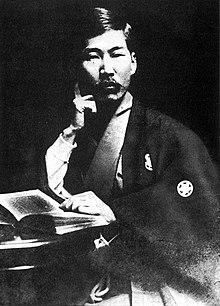

"[4] Kōtoku Shūsui, who would later become a leading anarchist, started off as a supporter of liberal parties including the Rikken Jiyūtō in the 1890s, even acting as the English translator for their newspaper for two years.

[10] Heimin Shinbun made a point of announcing their lack of ill will towards Russian socialists, and Kōtoku translated Marx's The Communist Manifesto into Japanese for the first time, published in the newspaper in its anniversary issue, for which he was fined.

[13] Kōtoku's imprisonment only gave him further opportunities to read leftist literature, such as Peter Kropotkin's Fields, Factories and Workshops, and he claimed in August 1905 that "Indeed, I had gone [to prison] as a Marxian Socialist and returned as a radical Anarchist.

[18] They also published an 'Open Letter' addressed to Emperor Meiji threatening his assassination in 1907, which provoked Japanese politicians to implement harsher crackdowns on left-wing groups.

[22] In September 1906, Kōtoku received a letter from Kropotkin himself, which he published in the socialist press in November 1906, which promoted the rejection of parliamentary tactics in favour of what he called "anti-political syndicalism".

[23] In early 1907, he published a series of articles expanding upon this idea, including the most famous, which was titled "The Change In My Thought", in which he argued that "A real social revolution cannot possibly be achieved by means of universal suffrage and a parliamentary policy.

The ideas promoted by Kōtoku had seriously challenged the party program and its pledge to observe reformist tactics, and a vigorous debate ensued between the 'soft' pro-parliamentary and 'hard' pro-direct action factions.

Many significant figures in the nascent movement were arrested, including Ōsugi Sakae, Hitoshi Yamakawa, Kanno Sugako, and Kanson Arahata.

[33] When Takichi Miyashita had little success when distributing a pamphlet by Buddhist anarchist Uchiyama Gudō that was critical of the Emperor, he became determined out of frustration to assassinate the figurehead of the Japanese state.

[37] The High Treason trial and its fallout marked the start of the 'winter period' (冬時代, fuyu jidai) of Japanese anarchism, in which left-wing organisations were tightly monitored and controlled, and militants and activists were tailed 24 hours a day by police.

[36] Together, the two began to publish a journal in October 1912 called Modern Thought (Kindai Shisō), which explored anarchist syndicalism through a literary and philosophical lens, so as to avoid government persecution.

[39] Generally speaking, Ōsugi's endeavours were strongly academic and theoretical in nature at this point, and in his literary work he became influenced by thinkers such as Henri Bergson, Georges Sorel, Max Stirner, and Friedrich Nietzsche.

[40] In October 1914, Ōsugi and Arahata attempted to replace Modern Thought with a revival of the old Heimin Shinbun newspaper, but this was met with repeated suppression of its issues and was forced to fold in March 1915.

[41] However, when Kropotkin, a leading advocate of the former faction, signed the Manifesto of the Sixteen in support of the Allied cause in the First World War, it detracted sharply from his reputation amongst Japanese anarchists.

During the First World War, Japanese industry rapidly expanded, and combined with inspiration by the 1917 Russian Revolution, this led to a huge growth in the labour movement.

According to writer and activist Harumi Setouchi, Itō, Ōsugi, and his 6 year old nephew were arrested, beaten to death and thrown into an abandoned well by a squad of military police led by Lieutenant Masahiko Amakasu.

[65] He interpreted the two as being essentially similar, as Bolshevik industrialisation in Russia involved the same exploitative elements that capitalism did, namely the division of labour and a failure to focus on the livelihood of the people.

[67] Instead, Hatta advocated for a decentralised society in which local communes engaged mainly in agriculture and small-scale industry, which he perceived as the only way in which unequal distribution of power could be avoided.

Early on in its existence, it openly supported the cause of these unions alongside the syndicalist idea of class struggle, although pure anarchists such as Hatta Shūzō were also a part of the organisation from the very start.

Hatta published a serialised article in Kokushoku Seinen called 'An Investigation Into Syndicalism' in late 1927, which harshly attacked anarcho-syndicalism, and Kokuren quickly became a stronghold of pure anarchism.

When Zenkoku Jiren mistakenly sent delegates to a conference organised by the Bolshevik Profintern in 1927, Kokuren was highly sceptical of their actions and openly decried 'opportunist' elements within their counterpart.

[82] A booklet by Iwasa Sakutarō called 'Anarchists Answer Like This', published in July 1927, further provoked the split by criticising anarcho-syndicalist theory such as the idea of class struggle.

[102] Land reform instituted after the war also effectively eliminated the class of tenant farmers that had formed the core base of the pre-war anarchist movement.

[113] Due to the development of Japanese left-wing thought and translations of major works, Koreans in Japan often had greater access to both socialist and anarchist materials, bolstering the spread of these ideologies.

It proclaimed support for the amalgamation of Japan and Korea, and ultimately the entire world,[122] an idea that stemmed from the prominent transnationalist aspect of Korean anarchist thought in the era.

[126] Iwasa, together with other Japanese, Taiwanese, Korean, and Chinese activists, worked together in joint projects such as the Shanghai Labour University, an experiment with new educational institutions and theories.