Anarchist criminology

[2][3][4] Accordingly, anarchism questions the conventional wisdom produced by these forms of power, including ideas about universality, and pursues pluralism and multiplicity in the epistemic and aesthetic domains.

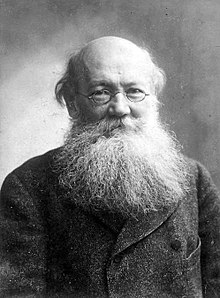

[7] The roots of anarchist criminology lie in the critiques of law and legality formulated by classical anarchists including Mikhail Bakunin, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman, William Godwin, Peter Kropotkin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Max Stirner, each of whom envisioned forms of social order that would, in the absence of the state, maximise individual freedom and encourage self-organisation.

[11] Kropotkin thought that most crime would vanish following the abolition of private property and the replacement of profit and competition by cooperation and human need as society's guiding principles.

[15] The anarchist criminologist Jeff Ferrell also identifies the anarcho-syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) as a precursor of anarchist criminology: in the United States in the early 20th century the IWW identified "law and order" as a form of power instantiated by the ruling class at the expense of the working class, and developed the tactic of the "on the job strike", in which workers stringently obey rules and regulations in order to slow work.

[6][19] Anarchist criminology contends that law solidifies and reproduces existing structures of power, thereby placing limitations on possible social relations and exacerbating crime and violence.

[23] Ferrell describes anarchist criminology as invested in a process of demystification through which the epistemologies of certainty, truth and justice that are used to justify authority are called into question.

[26] Ferrell argues that instead of adhering to a single masterplan, anarchist criminology is characterised by a "spirit of eclectic inclusivity" and an embrace of "fluid communities of uncertainty and critique.

[29] Anarchist criminology argues that if law must exist, its function must be transformed so that instead of protecting private property, social privilege and state power, it would ensure tolerance and diversity.

[18] Larry Tifft and Dennis Sullivan argue that advocates of anarchist criminology "are interested not only in pointing to those persons, groups, organizations, and nation-states that deny people their needs in everyday life but also in fostering social arrangements that alleviate pain and suffering by providing for everyone's needs.

"[44][45] Ferrell proposes that this entails "that anarchist criminologists must look up and down at the same time—that is, must pay attention to the subtleties of legal and political authority, the nuances of lived criminal events, and the interconnections between the two.

Moreover, anarchists would agree with many feminist and postmodernist theorists that such visceral passions matter as methods of understanding and resistance outside the usual confines of rationality and respect.

"[47]Prominent anarchist criminologists since the 1970s have included Randall Amster, who has explored anti-authoritarian forms of conflict resolution in anarchist communities;[10] Bruce DiCristina, whose work draws on the thought of Paul Feyerabend in order to critique criminology and criminal justice;[48] Jeff Ferrell, whose work examines the relationships between legal authority, resistance and criminality;[10][49] Harold Pepinsky, who in 1978 published an article on "communist anarchism as an alternative to the rule of criminal law", which introduced an approach that later came to be known as peacemaking criminology;[10][49] Dennis Sullivan;[9][10][49] and Larry Tifft, who argued for the replacement of state law with a face-to-face form of justice grounded in humans' needs.

"[11] Michael Welch argued in 2005 that although its application to the study of lawlessness remains limited to a handful of works, anarchist criminology offers the field a valuable framework for deconstructing the state, its authority, and its machinery of repressive social control, as well as the resistance it evokes .... Anarchist criminology has the potential to further advance critical penology by offering a fluid approach to law and justice, inviting scholars to incorporate an array of sociological concepts into their analyses of the state, the criminal justice system, and the corrections apparatus.

[51] Such methods, Vysotsky suggests, are in keeping with the central tenets of anarchism, and so "represent a challenge to the pacifist orientation of anarchist criminology".