Russian nihilist movement

Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin, as stated in the Encyclopædia Britannica, "defined nihilism as the symbol of struggle against all forms of tyranny, hypocrisy, and artificiality and for individual freedom.

[4] It did however, incorporate theories of hard determinism, atheism, materialism, positivism, and egoism[5] in an aim to assimilate and distinctively recontextualize core elements of the Age of Enlightenment into Russia while dropping the Westernizer approach of the previous generation.

[15] The Encyclopædia Britannica attributes the probable first use of the term in Russian publication to Nikolai Nadezhdin who, like Vasily Bervi-Flerovsky and Vissarion Belinsky after him, used it synonymously with skepticism.

[19] However, it was not until 1862 that the term was first popularized when Ivan Turgenev's celebrated novel Fathers and Sons used nihilism to describe the disillusionment of the younger generation, the šestidesjatniki, towards both the traditionalists and the progressive reformists that came before them, the sorokovniki.

[27] Contemporary scholarship has challenged the equating of Russian nihilism with mere skepticism, instead identifying it with the fundamentally Promethean character of the nihilist movement.

[40] "Their attraction to the airy heights of idealism was partly a result of the stultifying political atmosphere of the autocracy, but was also an unintended consequence of Tsar Nicholas I's attempt to Prussianize Russian society", writes historian M. A. Gillespie.

[43] The raznochintsy (meaning "of indeterminate rank"), which began as an 18th-century legal designation for those of the miscellaneous lower-middle classes, by the 19th century had become a distinct yet ambiguously defined social stratum with a growing presence in the Russian intelligentsia.

[51] The origins of this followed from Ludwig Feuerbach as a direct reaction to the German idealism which had found such popularity under the sorokovniki—namely the works of Friedrich Schelling, Georg Hegel and Johann Fichte.

[54] After severely struggling in the face of censorship — from which much of its core content is left unclear and obscured — the open academic development of Russian materialism would later be suppressed by the state after an attempted assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1866,[55] and would not see a significant intellectual revival until the late nineteenth century.

[62] Alexander II's ascent to the throne brought liberal reforms to university entry regulations and loosened control over publication, much to the movement's good fortune.

Where those early thinkers such as Bakunin and Herzen had found use of Fichte and Hegel, the younger generation were set on their rejection of idealism and were more ready to abandon politics as well.

Further influence came from the utilitarian ideas of John Stuart Mill, though his bourgeois liberalism was detested, and later from evolutionary biologists Charles Darwin and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck.

[67] Dobrolyubov had in fact occasionally used the term nihilism prior to its popularization at the hands of Turgenev, which he had picked up from sociologist and fellow šestidesjatnik Vasily Bervi-Flerovsky, who in turn had used it synonymously with skepticism.

These reforms however, while conceding an expansion of the raznochinnaya intelligentsia, refused to grant more rights to students and university admittance remained exclusively male.

[76] Historian Kristian Petrov writes: Young nihilist men dressed in ill-fitting dark coats, aspiring to look like unpolished workers, let their hair grow bushy and often wore blue-tinted glasses.

Correspondingly, the young women cut their hair shorter, wore large plain dresses and could be seen with a shawl or a big hat, together with the characteristic glasses.

[79] Pisarev famously published his own review at the time of the novel's release, where he championed Bazarov as the role model for the new generation and celebrated the embrace of nihilism.

[80] The atmosphere of the 1860s had led to a period of great social and economic upheaval across the country and the driving force of revolutionary activism was taken up by university students in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

[83] Comparing to Ivan Goncharov's The Precipice, which he describes as a caricature of nihilism, Peter Kropotkin states in his memoirs that Bazarov was a more admirable portrayal yet was still found dissatisfying to nihilists for his harsh attitude, his coldness towards his old parents, and his neglect of duties as a citizen.

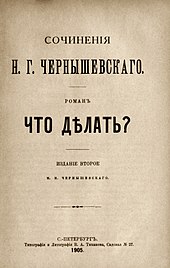

[85] By an extraordinary failure of bureaucracy, government censors allowed the book to be published without any trouble despite it being the most openly revolutionary work of its era and a direct product of the suppression Chernyshevsky had faced.

In the meantime, extensive castigation of nihilism had found its place in Russian publication, official government documents, and a burgeoning trend of antinihilistic literature.

Notable earlier works of this literary current include Aleksey Pisemsky's Troubled Seas (1863), Nikolai Leskov's No Way Out (1864), and Viktor Klyushnikov's The Mirage (1864).

[88] "[Chenyshevsky's] virtuous fictional creations were not the genuine, flesh-and-blood egoists whose growing presence in Russia Dostoevsky feared", writes scholar James P. Scanlan.

[90] Chernyshevsky gained a legendary reputation as a martyr of the radical movement and,[91] unlike Mikhail Bakunin, not once did he plead for mercy or pardon during his treatment at the hands of the state.

[94] From the revolutionary turmoil of the years 1859–1861, which had included peasant uprisings in Bezdna and Kandievka, the secret society Zemlya i volya emerged under the strong influence of Nikolay Chernyshevsky's writings.

[99] Dmitry Karakozov, who was the cousin of Nikolai Ishutin, joined the Circle in 1866 and on April 4 of that year carried out an attempted assassination of Alexander II, firing a shot at the Tsar at the gates of the Summer Garden in Saint Petersburg.

[104] Zemlya i volya was re-established in 1876,[105] originally under the name Severnaia revoliutsionno-narodnicheskaia gruppa (Northern Revolutionary-Populist Group), by Mark Natanson and Alexander Dmitriyevich Mikhaylov.

He secretly gathered the group members closest to him, declared that the mysterious imaginary central committee possessed the evidence of Ivanov's betrayal, albeit not producible for security reasons, and obtained his death sentence.

[113] Author Ronald Hingley wrote: "On the evening of 21 November 1869 the victim [Ivanov] was accordingly lured to the premises of the Moscow School of Agriculture, a hotbed of revolutionary sentiment, where Nechayev killed him by shooting and strangulation, assisted without great enthusiasm by three dupes.

[114] Due to his charisma and force of will, Nechayev continued to influence events, maintaining a relationship to Narodnaya Volya and weaving even his jailers into his plots and escape plans.