Narodnaya Volya

'People's Will') was a late 19th-century revolutionary socialist political organization operating in the Russian Empire, which conducted assassinations of government officials in an attempt to overthrow the autocratic Tsarist system.

[7] Socialist study circles (kruzhki) began to emerge in Russia during the decade of the 1870s, populated primarily by idealistic students in major urban centers such as St. Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, and Odessa.

[8] Efforts to propagandize revolutionary and socialist ideas among factory workers and peasants were quickly met with state repression, however, with the Tsarist secret police (Okhrana) identifying, arresting, and jailing agitators.

[10] Fired with messianic zeal, perhaps 2,000 people left for rural posts in the spring; by the fall some 1,600 of these found themselves arrested and jailed, failing to make the slightest headway in fomenting agrarian revolution.

[12] As an underground political party marked by extreme secrecy in the face of secret police repression, few primary records originating from the group documenting its existence have survived.

[16] These ideas were borrowed directly from Mikhail Bakunin, a radicalized émigré nobleman from Tver guberniia regarded as the father of collectivist anarchism.

[20] The organization began to look at regicide as the highest manifestation of political action, culminating in a December 1879 assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II by the Zemlevolets A. K. Soloviev (1846–1879).

[23] Efforts to reconcile the two wings were unsuccessful and a split was formalized on 15 August 1879, by a commission appointed to divide the organization's assets.

[22] During the latter part of 1879, those favoring study circles and propaganda to build a revolutionary movement from the ground up, exemplified by Plekhanov and his co-thinkers, launched independent activity as a new organization called Chërnyi Peredel (Russian: Чёрный передел, "Black Repartition").

[24] During the first months after its formation, Narodnaya Volya founded or co-opted workers study circles in the major cities of St. Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa, Kiev, and Kharkov.

[26] The organization promulgated a program which called for "complete freedom of conscience, speech, press, assembly, association, and electoral agitation".

Mikhailovsky (1842–1904) contributing two finely crafted "political letters" on the topic to two early issues of the party's official organ.

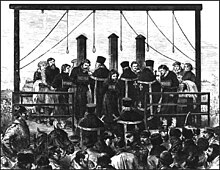

[31] Democratic control of the party apparatus was deemed impossible under existing political conditions and the organization was centrally directed by its self-selecting Executive Committee, which included, among others Alexander Mikhailov, Andrei Zhelyabov (1851–1881), Sophia Perovskaya (1853–1881), Vera Figner (1852–1942), Nikolai Morozov (1854–1946), Mikhail Frolenko (1848–1938), Aaron Zundelevich (1852–1923), Savely Zlatopolsky (1855–1885) and Lev Tikhomirov (1852–1923).

[39] One French diplomat likened the Tsar to a ghost—"pitiful, aged, played out, and choked by a fit of asthmatic coughing at every word".

[40] Repression was ratcheted upwards, with two Narodnaya Volya activists executed in Kiev the following month for the crime of distributing revolutionary leaflets.