Early modern human

The divergence of the lineage leading to H. sapiens out of ancestral H. erectus (or an intermediate species such as Homo antecessor) is estimated to have occurred in Africa roughly 500,000 years ago.

[48][49] The "gracile" or lightly built skeleton of anatomically modern humans has been connected to a change in behavior, including increased cooperation and "resource transport".

[50][51] There is evidence that the characteristic human brain development, especially the prefrontal cortex, was due to "an exceptional acceleration of metabolome evolution ... paralleled by a drastic reduction in muscle strength.

"[52] The Schöningen spears and their correlation of finds are evidence that complex technological skills already existed 300,000 years ago, and are the first obvious proof of an active (big game) hunt.

[note 5] There have, however, been no reports of the survival of Y-chromosomal or mitochondrial DNA clearly deriving from archaic humans (which would push back the age of the most recent patrilinear or matrilinear ancestor beyond 500,000 years).

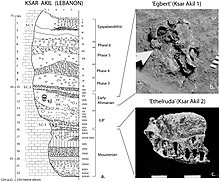

[note 6] Dispersal of early H. sapiens begins soon after its emergence, as evidenced by the North African Jebel Irhoud finds (dated to around 315,000 years ago).

Neanderthal admixture, in the range of 1–4%, is found in all modern populations outside of Africa, including in Europeans, Asians, Papua New Guineans, Australian Aboriginals, Native Americans, and other non-Africans.

[84][85][86] Recent admixture analyses have added to the complexity, finding that Eastern Neanderthals derive up to 2% of their ancestry from anatomically modern humans who left Africa some 100 kya.

[89] In September 2019, scientists reported the computerized determination, based on 260 CT scans, of a virtual skull shape of the last common human ancestor to modern humans/H.

[33][4] According to a study published in 2020, there are indications that 2% to 19% (or about ≃6.6 and ≃7.0%) of the DNA of four West African populations may have come from an unknown archaic hominin which split from the ancestor of humans and Neanderthals between 360 kya to 1.02 mya.

The term "anatomically modern humans" (AMH) is used with varying scope depending on context, to distinguish "anatomically modern" Homo sapiens from archaic humans such as Neanderthals and Middle and Lower Paleolithic hominins with transitional features intermediate between H. erectus, Neanderthals and early AMH called archaic Homo sapiens.

[92] It has since become more common to designate Neanderthals as a separate species, H. neanderthalensis, so that AMH in the European context refers to H. sapiens, but the question is by no means resolved.

[114] Physiological or phenotypical changes have been traced to Upper Paleolithic mutations, such as the East Asian variant of the EDAR gene, dated to c. 35,000 years ago.

An even more recent adaptation has been proposed for the Austronesian Sama-Bajau, developed under selection pressures associated with subsisting on freediving over the past thousand years or so.

While most clear evidence for behavioral modernity uncovered from the later 19th century was from Europe, such as the Venus figurines and other artefacts from the Aurignacian, more recent archaeological research has shown that all essential elements of the kind of material culture typical of contemporary San hunter-gatherers in Southern Africa was also present by at least 40,000 years ago, including digging sticks of similar materials used today, ostrich egg shell beads, bone arrow heads with individual maker's marks etched and embedded with red ochre, and poison applicators.

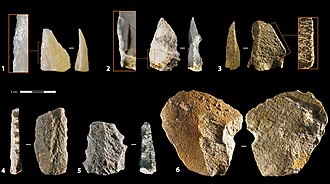

[138] There is also a suggestion that "pressure flaking best explains the morphology of lithic artifacts recovered from the c. 75-ka Middle Stone Age levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa.

Further reports of research on cave sites along the southern African coast indicate that "the debate as to when cultural and cognitive characteristics typical of modern humans first appeared" may be coming to an end, as "advanced technologies with elaborate chains of production" which "often demand high-fidelity transmission and thus language" have been found at the South African Pinnacle Point Site 5–6.

[141] This might have led to human groups who were seeking refuge from the inland droughts, expanded along the coastal marshes rich in shellfish and other resources.

The use of rafts and boats may well have facilitated exploration of offshore islands and travel along the coast, and eventually permitted expansion to New Guinea and then to Australia.

The Blombos Cave site in South Africa, for example, is famous for rectangular slabs of ochre engraved with geometric designs.

[143][144] Ostrich egg shell containers engraved with geometric designs dating to 60,000 years ago were found at Diepkloof, South Africa.

Analysis shows that a liquefied pigment-rich mixture was produced and stored in the two abalone shells, and that ochre, bone, charcoal, grindstones and hammer-stones also formed a composite part of the toolkits.

Evidence for the complexity of the task includes procuring and combining raw materials from various sources (implying they had a mental template of the process they would follow), possibly using pyrotechnology to facilitate fat extraction from bone, using a probable recipe to produce the compound, and the use of shell containers for mixing and storage for later use.

[158][159][160] Modern behaviors, such as the making of shell beads, bone tools and arrows, and the use of ochre pigment, are evident at a Kenyan site by 78,000-67,000 years ago.

[161] Evidence of early stone-tipped projectile weapons (a characteristic tool of Homo sapiens), the stone tips of javelins or throwing spears, were discovered in 2013 at the Ethiopian site of Gademotta, and date to around 279,000 years ago.

[162] Expanding subsistence strategies beyond big-game hunting and the consequential diversity in tool types have been noted as signs of behavioral modernity.

[163] Establishing a reliance on predictable shellfish deposits, for example, could reduce mobility and facilitate complex social systems and symbolic behavior.

[146] Humans in North Africa (Nazlet Sabaha, Egypt) are known to have dabbled in chert mining, as early as ≈100,000 years ago, for the construction of stone tools.

[164][165] Evidence was found in 2018, dating to about 320,000 years ago at the site of Olorgesailie in Kenya, of the early emergence of modern behaviors including: the trade and long-distance transportation of resources (such as obsidian), the use of pigments, and the possible making of projectile points.

[166][167][168] In 2019, further evidence of Middle Stone Age complex projectile weapons in Africa was found at Aduma, Ethiopia, dated 100,000–80,000 years ago, in the form of points considered likely to belong to darts delivered by spear throwers.

(in Cleveland Museum of Natural History )

Features compared are the braincase shape, forehead , browridge , nasal bone projection , cheek bone angulation , chin and occipital contour