History of Athens

During the early Middle Ages, the city experienced a decline, then recovered under the later Byzantine Empire and was relatively prosperous during the period of the Crusades (12th and 13th centuries), benefiting from Italian trade.

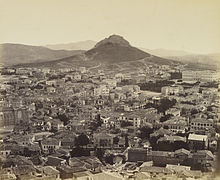

Following a period of sharp decline under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, Athens re-emerged in the 19th century as the capital of the independent and self-governing Greek state.

[1] The origin myth explaining how Athens acquired this name through the legendary contest between Poseidon and Athena was described by Herodotus,[2] Apollodorus,[3] Ovid, Plutarch,[4] Pausanias and others.

[2] Plato, in his dialogue Cratylus, offers an etymology of Athena's name connecting it to the phrase ἁ θεονόα or hē theoû nóēsis (ἡ θεοῦ νόησις, 'the mind of god').

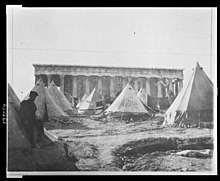

[7] There is evidence that the site on which the Acropolis ('high city') stands was first inhabited in the Neolithic period, perhaps as a defensible settlement, around the end of the fourth millennium BC or a little later.

One of the most important religious sites in ancient Athens was the Temple of Athena, known today as the Parthenon, which stood on top of the Acropolis, where its evocative ruins still stand.

[10] Between 1250 and 1200 BC, to feed the needs of the Mycenaean settlement, a staircase was built down a cleft in the rock to reach a water supply that was protected from enemy incursions,[11] comparable to similar works carried out at Mycenae.

Iron Age burials, in the Kerameikos and other locations, are often richly provided for and demonstrate that from 900 BC onwards Athens was one of the leading centres of trade and prosperity in the region; as were Lefkandi in Euboea and Knossos in Crete.

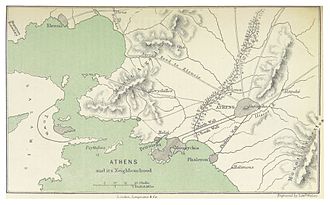

[12] This position may well have resulted from its central location in the Greek world, its secure stronghold on the Acropolis and its access to the sea, which gave it a natural advantage over inland rivals such as Thebes and Sparta.

From later accounts, it is believed that these kings stood at the head of a land-owning aristocracy known as the Eupatridae (the 'well-born'), whose instrument of government was a Council which met on the Hill of Ares, called the Areopagus and appointed the chief city officials, the archons and the polemarch (commander-in-chief).

The poorest class, the Thetai, (Ancient Greek Θήται) who formed the majority of the population, received political rights for the first time and were able to vote in the Ecclesia (Assembly).

The new system laid the foundations for what eventually became Athenian democracy, but in the short-term it failed to quell class conflict and after twenty years of unrest the popular party, led by Peisistratos, seized power.

The Assembly was open to all citizens and was both a legislature and a supreme court, except in murder cases and religious matters, which became the only remaining functions of the Areopagus.

Since the loss of the war was largely blamed on democratic politicians such as Cleon and Cleophon, there was a brief reaction against democracy, aided by the Spartan army (the rule of the Thirty Tyrants).

But then the Greek cities (including Athens and Sparta) turned against Thebes, whose dominance was stopped at the Battle of Mantinea (362 BC) with the death of its military-genius leader Epaminondas.

In the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), Philip II's armies defeated an alliance of some of the Greek city-states including Athens and Thebes, forcing them into a confederation and effectively limiting Athenian independence.

[17] Philippides of Paiania, one of the wealthiest Athenian aristocratic oligarchs, campaigned for Philip II during the Battle of Chaeronea and proposed in the Assembly decrees honoring Alexander the Great for the Macedonian victory.

[19] Some of the most important figures of Western cultural and intellectual history lived in Athens during this period: the dramatists Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes, the physician Hippocrates, the philosophers Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, the historians Herodotus, Thucydides and Xenophon, the poet Simonides, the orators Antiphon, Isocrates, Aeschines, and Demosthenes, and the sculptor Phidias.

The leading statesman of the mid-fifth century BC was Pericles, who used the tribute paid by the members of the Delian League to build the Parthenon and other great monuments of classical Athens.

In 88–85 BC, most Athenian fortifications and homes were leveled by the Roman general Sulla after the Siege of Athens and Piraeus, although many civic buildings and monuments were left intact.

In the early 4th century AD, the eastern Roman empire began to be governed from Constantinople, and with the construction and expansion of the imperial city, many of Athens's works of art were taken by the emperors to adorn it.

[29] The emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565) banned the teaching of philosophy by pagans in 529,[30] an event whose impact on the city is much debated,[29] but is generally taken to mark the end of the ancient history of Athens.

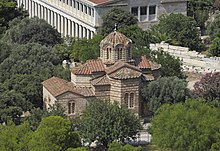

[29] Invasion of the empire by the Turks after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, and the ensuing civil wars, largely passed the region by and Athens continued its provincial existence unharmed.

[31] As the Ottoman Sultan rode into the city, he was greatly struck by the beauty of its ancient monuments and issued a firman (imperial edict) forbidding their looting or destruction, on pain of death.

A shot fired during the bombardment of the Acropolis caused a powder magazine in the Parthenon to explode (26 September), and the building was severely damaged, giving it largely the appearance it has today.

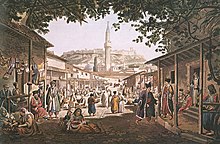

[36] Its Greek population possessed a considerable degree of self-government, under a council of primates composed of the leading aristocratic families, along with the city's metropolitan bishop.

The pasha fled to the Acropolis, where he was besieged by the Athenians, until the Ottoman governor of Negroponte intervened and restored order, imprisoning the metropolitan bishop and imposing a heavy fine on the Greek community.

Henceforth it would be leased as a malikhane, a form of tax farming where the owner bought the proceeds of the city for a fixed sum, and enjoyed them for life.

The Turkish community numbered several families established in the city since the Ottoman conquest; and their relations with their Christian neighbours were friendlier than elsewhere, as they had assimilated themselves to a degree, even to the point of drinking wine.

[36] During the Orlov Revolt of 1770 the Athenians, with the exception of the younger men, remained cautious and passive, even when the Greek rebel chieftain Mitromaras seized Salamis.

Rev : Owl standing facing, ΑΘΕ (ΑΘΗΝΑΙΩΝ – of Athenians). Commemorative issue, representing the Athenian military domination.