Music of ancient Greece

The word music comes from the Muses, the daughters of Zeus and patron goddesses of creative and intellectual endeavours.

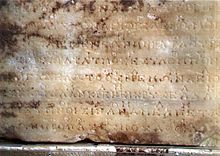

They developed tuning systems and harmonic principles that focused on simple integers and ratios, laying a foundation for acoustic science; however, this was not the only school of thought in ancient Greece.

[3]: 132 Aristoxenus, who wrote a number of musicological treatises, for example, studied music with a more empirical tendency.

The sarcophagus of Hagia Triada shows that the aulos was present during sacrifices as early as 1300 BC.

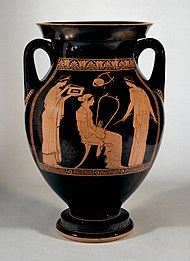

[7]: 2 Music was also present during times of initiation, worship, and religious celebration, playing very integral parts of the sacrificial cults of Apollo and Dionysus.

As in Plato's dialogue Ion, Socrates uses both the words "sing" and "speak" in connection with the Homeric epics,[9][page needed] however there are heavy implications that they have been at least recited unaccompanied by instruments, in a sing-song chant.

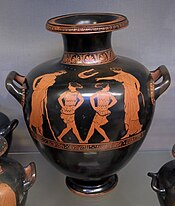

[3]: 148 In Greek mythology: Amphion learned music from Hermes and then with a golden lyre built Thebes by moving the stones into place with the sound of his playing; Orpheus, the master-musician and lyre-player, played so magically that he could soothe wild beasts; the Orphic creation myths have Rhea "playing on a brazen drum, and compelling man's attention to the oracles of the goddess";[11]: 30 or Hermes [showing to Apollo] "... his newly-invented tortoise-shell lyre and [playing] such a ravishing tune on it with the plectrum he had also invented, at the same time singing to praise Apollo's nobility[11]: 64 that he was forgiven at once ..."; or Apollo's musical victories over Marsyas and Pan.

[11]: 77 There are many such references that indicate that music was an integral part of the Greek perception of how their race had even come into existence and how their destinies continued to be watched over and controlled by the Gods.

[17] When Orpheus' wife, Eurydice, died, he played a song so mournful that it caused the gods and all the nymphs to weep.

The lyre, cithara, aulos, barbiton, hydraulis, and salpinx all found their way into the music of ancient Rome.

The rule was to listen silently and learn; boys, teachers, and the crowd were kept in order by threat of the stick.

But later, an unmusical anarchy was led by poets who had natural talent, but were ignorant of the laws of music ...

Through foolishness they deceived themselves into thinking that there was no right or wrong way in music, that it was to be judged good or bad by the pleasure it gave.

[28]From his references to "established forms" and "laws of music" we can assume that at least some of the formality of the Pythagorean system of harmonics and consonance had taken hold of Greek music, at least as it was performed by professional musicians in public, and that Plato was complaining about the falling away from such principles into a "spirit of law-breaking".

This limit on tone types creates relatively few kinds of scales in modern Western music compared to that of the Greeks, who used the placement of whole-tones, half-tones, and even quarter-tones (or still smaller intervals) to develop a large repertoire of scales, each with a unique ethos.

The Greek concepts of scales (including the names) found its way into later Roman music and then the European Middle Ages to the extent that one can find references to, for example, a "Lydian church mode", although name is simply a historical reference with no relationship to the original Greek sound or ethos.

From the descriptions that have come down to us through the writings of those such as Plato, Aristoxenus[30] and, later, Boethius,[31] we can say with some caution that the ancient Greeks, at least before Plato, heard music that was primarily monophonic; that is, music built on single melodies based on a system of modes / scales, themselves built on the concept that notes should be placed between consonant intervals.

It is a commonplace of musicology to say that harmony, in the sense of a developed system of composition, in which many tones at once contribute to the listener's expectation of resolution, was invented in the European Middle Ages and that ancient cultures had no developed system of harmony—that is, for example, playing the third and seventh above the dominant, in order to create the expectation for the listener that the tritone will resolve to the third.

The lyre should be used together with the voices ... the player and the pupil producing note for note in unison, Heterophony and embroidery by the lyre—the strings throwing out melodic lines different from the melodia which the poet composed; crowded notes where his are sparse, quick time to his slow ... and similarly all sorts of rhythmic complications against the voices—none of this should be imposed upon pupils ...[34]Aristotle had a strong belief that music should be a part of one's education, alongside reading and writing, and gymnastics.

According to Aristotle, all men could agree that music was one of the most pleasurable things, so to have this as a means of leisure was only logical.

Since music combined relaxing ourselves, along with others, Aristotle claimed that learning an instrument was essential to our development.

It is important to note that since music helps in forming the character, it could cause either adverse or pleasant effects.

[35]: 16 Learning music should not interfere with the younger years, nor should it damage the body in a way that a person is unable to fulfill duties in the military.

Those that have learned music in education should not be at the same level as a professional, but they should have a greater knowledge than the slaves and other commoners.