Ancient Greek warfare

The Greek 'Dark Ages' drew to an end as a significant increase in population allowed urbanized culture to be restored, which led to the rise of the city-states (Poleis).

But this was unstable, and the Persian Empire sponsored a rebellion by the combined powers of Athens, Thebes, Corinth and Argos, resulting in the Corinthian War (395–387 BC).

The rise of the Macedonian Kingdom is generally taken to signal the beginning of the Hellenistic period, and certainly marked the end of the distinctive hoplite battle in Ancient Greece.

The major innovation in the development of the hoplite seems to have been the characteristic circular shield (aspis), roughly 1 m (3.3 ft) in diameter, and made of wood faced with bronze.

At least in the Archaic Period, the fragmentary nature of Ancient Greece, with many competing city-states, increased the frequency of conflict, but conversely limited the scale of warfare.

If battle was refused by one side, it would retreat to the city, in which case the attackers generally had to content themselves with ravaging the countryside around, since the campaign season was too limited to attempt a siege.

Casualties were slight compared to later battles, amounting to anywhere between 5 and 15% for the winning and losing sides respectively,[7] but the slain often included the most prominent citizens and generals who led from the front.

Cavalry had always existed in Greek armies of the classical era but the cost of horses made it far more expensive than hoplite armor, limiting cavalrymen to nobles and the very wealthy (social class of hippeis).

During the early hoplite era cavalry played almost no role whatsoever, mainly for social, but also tactical reasons, since the middle-class phalanx completely dominated the battlefield.

The eventual triumph of the Greeks was achieved by alliances of many city-states (the exact composition changing over time), allowing the pooling of resources and division of labour.

The Greco-Persian Wars (499–448 BC) were the result of attempts by the Persian Emperor Darius the Great, and then his successor Xerxes I to subjugate Ancient Greece.

After several days of stalemate at Marathon, the Persian commanders attempted to take strategic advantage by sending their cavalry (by ship) to raid Athens itself.

[citation needed] The Persians had acquired a reputation for invincibility, but the Athenian hoplites proved crushingly superior in the ensuing infantry battle.

The visionary Athenian politician Themistocles had successfully persuaded his fellow citizens to build a huge fleet in 483/82 BC to combat the Persian threat (and thus to effectively abandon their hoplite army, since there were not men enough for both).

Famously, Leonidas's men held the much larger Persian army at the pass (where their numbers were less of an advantage) for three days, the hoplites again proving their superiority.

Thermopylae provided the Greeks with time to arrange their defences, and they dug in across the Isthmus of Corinth, an impregnable position; although an evacuated Athens was thereby sacrificed to the advancing Persians.

Demoralised, Xerxes returned to Asia Minor with much of his army, leaving his general Mardonius to campaign in Greece the following year (479 BC).

At one point, the Greeks even attempted an invasion of Cyprus and Egypt (which proved disastrous), demonstrating a major legacy of the Persian Wars: warfare in Greece had moved beyond the seasonal squabbles between city-states, to coordinated international actions involving huge armies.

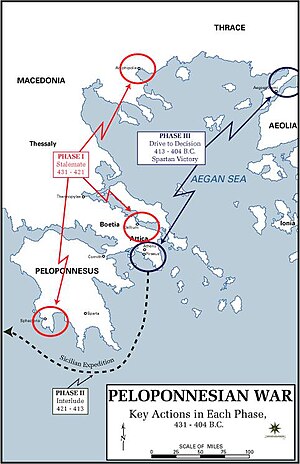

Tactically the Peloponnesian war represents something of a stagnation; the strategic elements were most important as the two sides tried to break the deadlock, something of a novelty in Greek warfare.

Far from the previously limited and formalized form of conflict, the Peloponnesian War transformed into an all-out struggle between city-states, complete with atrocities on a large scale; shattering religious and cultural taboos, devastating vast swathes of countryside and destroying whole cities.

Firstly, the Spartans permanently garrisoned a part of Attica, removing from Athenian control the silver mine which funded the war effort.

Although the Spartans did not attempt to rule all of Greece directly, they prevented alliances of other Greek cities, and forced the city-states to accept governments deemed suitable by Sparta.

This did not go unnoticed by the Persian Empire, which sponsored a rebellion by the combined powers of Athens, Thebes, Corinth and Argos, resulting in the Corinthian War (395–387 BC).

The Athenian general Iphicrates had his troops make repeated hit and run attacks on the Spartans, who, having neither peltasts nor cavalry, could not respond effectively.

Unlike the fiercely independent (and small) city-states, Macedon was a tribal kingdom, ruled by an autocratic king, and importantly, covering a larger area.

Once firmly unified, and then expanded, by Philip II, Macedon possessed the resources that enabled it to dominate the weakened and divided states in southern Greece.

Finally Phillip sought to establish his own hegemony over the southern Greek city-states, and after defeating the combined forces of Athens and Thebes, the two most powerful states, at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC, succeeded.

Now unable to resist him, Phillip compelled most of the city states of southern Greece (including Athens, Thebes, Corinth and Argos; but not Sparta) to join the Corinthian League, and therefore become allied to him.

The Macedonian phalanx was a supreme defensive formation, but was not intended to be decisive offensively; instead, it was used to pin down the enemy infantry, whilst more mobile forces (such as cavalry) outflanked them.

Alexander's fame is in no small part due to his success as a battlefield tactician; the unorthodox gambits he used at the battles of Issus and Gaugamela were unlike anything seen in Ancient Greece before.