Angela Morley

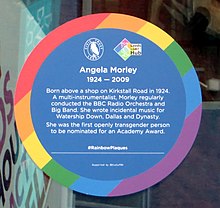

Angela Morley (10 March 1924[1][2] – 14 January 2009[3]) was an English composer and conductor who became familiar to BBC Radio listeners in the 1950s under the name of Wally Stott.

[6] As a mostly self-taught musician able to sight-read, Morley left school at age 15 to tour with Archie's Juvenile Band, earning a weekly wage of 10 shillings,[6] and also worked as a projectionist.

[6] With this band, she began writing arrangements for pay[6] and made a recording debut with the tracks "Waiting for Sally" and "Love in Bloom".

[6] She studied harmony and musical composition in London with the British-Hungarian composer Mátyás Seiber and conducting with the German conductor Walter Goehr.

[1] She was originally a composer of light music[2] or easy listening,[3] best known for pieces such as the jaunty "Rotten Row" and "A Canadian in Mayfair", the latter dedicated to Robert Farnon.

[6] In 1953, Morley became musical director for the British section of Philips Records,[1][2][3] arranging for and accompanying the company's artists alongside producer Johnny Franz.

[4] In 1962 and 1963, Morley arranged the United Kingdom entries for the Eurovision Song Contest, "Ring-A-Ding Girl" and "Say Wonderful Things", both sung by Ronnie Carroll.

She was also credited with a rhythmic drum solo in the 1960 horror film Peeping Tom, which a dancer plays on a tape recorder.

[2][10] In 1961, Morley provided the orchestral accompaniments for a selection of choral arrangements made by Norman Luboff for an RCA album that was recorded in London's Walthamstow Town Hall.

Due to worries about how she would be received publicly as a transgender woman, she declined opportunities to appear on television, such as on The Last Goon Show of All in 1972, though she continued to work with many of her previous colleagues.

[6] Though initially reluctant, citing lack of preparation and unfamiliarity with the novel, Morley wrote most of the score for the animated Watership Down film, released in 1978.

Following the success of Watership Down, Morley lived for a time in Brentwood, Los Angeles, where she began working for Warner Bros.[6] She permanently relocated to Los Angeles in 1979[3] and began working primarily on American television soundtracks, including those of Dynasty, Dallas, Cagney & Lacey, Wonder Woman[1], and Falcon Crest,[2] working with the music departments of major production companies, including Warner Bros., Paramount Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Universal Pictures and 20th Century Fox Television.

[4] She also lectured at the University of Southern California on film scoring[4] and founded the Chorale of the Alliance française of Greater Phoenix.

[1] According to her friend and colleague Max Geldray, she struggled with her gender identity throughout her life,[1][3] and according to her wife, Christine Parker, Morley probably tried hormone replacement therapy at some point before they met.

[1] Morley had two children with her first wife Beryl Stott: a daughter, Helen, who predeceased her in 1986, and a son, Brian,[3] who was living as of January 2009[update].

While working on The Goon Show, she made the acquaintance of Peter Sellers, and would eventually share fond memories of him to his biographer Ed Sikov.

[4] Morley was interviewed for the biography of her Goon Show colleague Peter Sellers by his biographer Ed Sikov prior to the book's publication in 2002.

[3] Sikov chose to refer to her as Wally Stott in the context of her past work but as Angela Morley in the present;[3] most posthumous writing about her follows a similar pattern.

[18] Morley's work has been compared to that of Wendy Carlos, given that they were both transgender women composing film scores in the same time period, though they never met; notably, the composer and researcher Jack Curtis Dubowsky analysed and compared their careers and styles in a chapter of his book Intersecting Film, Music, and Queerness.

This habit fundamentally misrepresents the filmmaking process, as film scholars Berys Gaut and C. Paul Sellors have argued.

She initially played in British dance bands, and spent much of her career composing music that was labelled as light and easy listening, as well as film scores and television soundtracks.

Light music and easy listening were generally not taken seriously or given much respect at the time that Morley was composing,[3] which Dubowsky credits partially to misogyny, due to the genre's association with femininity.

[3] On "Kehaar's Theme", Dubowsky notes the influence of Claude Debussy and comments that: For this theme, Morley takes a fragment of the opening flute motive of Debussy's 'Prélude à l'après midi d'un faune' [...] and spins it into a majestic, soaring, romantic swing waltz, an amalgamation of her work in French romantic style orchestral scoring and big band swing.

In addition to this mastery of style and technique, the opening I–bVI progression is fresh and contemporary; the 'borrowed' bVI chord had been used in earlier psych rock but would become prominently featured in the 'new wave' popular music of the time.

While not an 'easy listening' version of Debussy, 'Kehaar's Theme' nevertheless suggests how one might conceive of such a thing and execute it with finesse.He also notes that "Kehaar's Theme" incorporates polyrhythms and has an emphasis on string instruments, and that it draws from many of the genres Morley worked in: "classical, swing, jazz, light music, concert music, and film scoring".