Angels in art

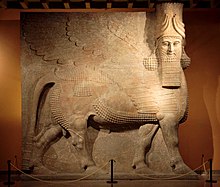

Normally given wings in art, angels are usually intended, in both Christian and Islamic art, to be beautiful, though several depictions go for more awe-inspiring or frightening attributes, notably in the depiction of the living creatures (which have bestial characteristics), ophanim (which are wheels) and cherubim (which have mosaic features);[1] As a matter of theology, they are spiritual beings who do not eat or excrete and are genderless.

[8] The earliest known Christian image of an angel, in the Cubicolo dell'Annunziazione in the Catacomb of Priscilla, which is dated to the middle of the third century, is a depiction of the Annunciation in which Gabriel is portrayed without wings.

In a third-century fresco of the Hebrew children in the furnace, in the cemetery of St. Priscilla, a dove takes the place of the angel, while a fourth-century representation of the same subject, in the coemeterium maius, substitutes the Hand of God for the heavenly messenger.

[10] The earliest known representation of angels with wings is on what is called the Prince's Sarcophagus, discovered at Sarigüzel, near Istanbul, in the 1930s, and attributed to the time of Theodosius I (379–395).

"[12] From then on Christian art generally represented angels with wings, as in the cycle of mosaics in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore (432–440).

Amelia R. Brown points out that legislation under Justinian indicates that many of them came from the Caucasus, having light eyes, hair, and skin, as well as the "comely features and fine bodies" desired by slave traders.

[14] Those "castrated in childhood developed a distinctive skeletal structure, lacked full masculine musculature, body hair and beards,...." As officials, they would wear a white tunic decorated with gold.

[5] Angels, especially the archangel Michael, who were depicted as military-style agents of God, came to be shown wearing Late Antique military uniform.

This could be either the normal military dress, with a tunic to about the knees, armour breastplate and pteruges, but also often the specific dress of the bodyguard of the Byzantine Emperor, with a long tunic and the loros, a long gold and jewelled pallium restricted to the Imperial family and their closest guards, and in icons to archangels.

The basic military dress it is still worn in pictures into the Baroque period and beyond in the West, and up to the present day in Eastern Orthodox icons.

Early Renaissance painters such as Jan van Eyck and Fra Angelico painted angels with multi-colored wings.

[17] In the Greek mythology, Eros and his Roman counterpart Cupid, are winged and have arrows they use to manipulate people to fall in love.

[18] In the late 19th century artists' model Jane Burden Morris came to embody an ideal of beauty for Pre-Raphaelite painters.

With the use of her long dark hair and features made somewhat more androgynous, they created a prototype Victorian angel which would appear in paintings and stained glass windows.

One example is the large mosaic mural Angels of the Heavenly Host in St Paul's, Bow Common, created during 1963–68 by Charles Lutyens.

[21] The 13th-century book Ajā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt (The Wonders of Creation) by Zakariya al-Qazwini describes Islamic angelology, and is often illustrated with many images of angels.

An undated manuscript of The Wonders of Creation from the Bavarian State Library in Munich includes depictions of angels both alone and alongside humans and animals.

[24] Similar, the fallen angel Iblis is shown during his moment of refusal to prostrate himself before the newly created Adam, leading to his banishment to the bottom of hell.

[29] Mainstream Rabbinic Judaism discourages focus from being placed on angels due to fears about idolatry and a desire to curtail any inclinations to polytheism.

[33] Cherubim in their classic Jewish description are typically creatures with features of a human, lion, bird, and cattle in some combination.

[40] The majority of ancient artwork portrayed Eros as being a slender yet well-built man wielding enormous sexual power.

The popularization of Erotes arises from the normalization of the Roman counterpart, Cupid, who has a bow and arrow that he uses to make people fall in love.

They generally are just in attendance, except that they may be amusing Christ or John the Baptist as infants in scenes of the Holy Family The Greek mythology associates Erotes with love and desire.

The majority of ancient artwork portrayed Eros as being a slender yet well-built man wielding enormous sexual power.

The popularization of Erotes arises from the normalization of the Roman counterpart, Cupid, who has a bow and arrow that he uses to make people fall in love.