Neo-Assyrian Empire

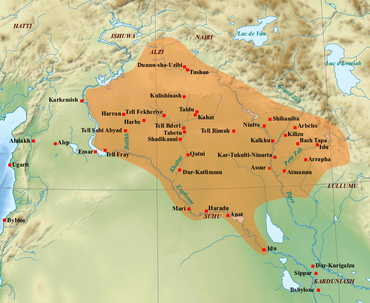

[19] One of the first conquests of Ashur-dan II had been Katmuḫu in this region, which he made a vassal kingdom rather than annexed outright; this suggests that the resources available to the early Neo-Assyrian kings were very limited and that the imperial reconquista project had to begin nearly from scratch.

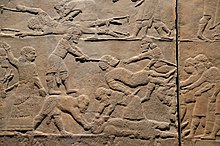

[43] In terms of personality, Ashurnasirpal was a complex figure; he was a relentless warrior[44] and one of the most brutal kings in Assyrian history,[45][f] but he also cared about the people, working to increase the prosperity and comfort of his subjects and being recorded as establishing extensive water reserves and food depots in times of crisis.

Though few of them became formally incorporated into the empire at this point, many kingdoms on the way paid tribute to Ashurnasirpal to avoid being attacked, including Carchemish and Patina, as well as Phoenician cities such as Sidon, Byblos, Tyre and Arwad.

In Shalmaneser IV's reign, Shamshi-ilu eventually grew bold enough to stop crediting the king at all in his inscriptions and instead claimed to act completely on his own, more openly flaunting his power.

[32] Through campaigns aimed at conquest and not just extraction of seasonal tribute, as well as reforms meant to efficiently organize the army and centralize the realm, Tiglath-Pileser is by some regarded as the first true initiator of Assyria's "imperial" phase.

[65] Early on, Tiglath-Pileser reduced the influence of the previously powerful magnates, dividing their territories into smaller provinces under the rule of royally appointed provincial governors and withdrawing their right to commission official building inscriptions in their own names.

[65] Tiglath-Pileser's conquests are, in addition to their extent, also noteworthy because of the large scale in which he undertook resettlement policies; he settled tens, if not hundreds, of thousand foreigners in both the Assyrian heartland and in far-away underdeveloped provinces.

[67] Shalmaneser managed to secure some lasting achievements; he was probably the Assyrian king responsible for conquering Samaria and thus bringing an end to the ancient Kingdom of Israel and he also appears to have annexed lands in northern Syria and Cilicia.

There, another movement, led by Yau-bi'di of Hamath and supported by Simirra, Damascus, Samaria and Arpad, also sought to regain independence and threatened to destroy the sophisticated provincial system imposed on the region under Tiglath-Pileser.

[93] While Esarhaddon's documents suggest that Shamash-shum-ukin was intended to inherit all of Babylonia, it appears that he only controlled the immediate vicinity of Babylon itself since numerous other Babylonian cities apparently ignored him and considered Ashurbanipal to be their king.

Ashurbanipal's reign also appears to have seen a growing disconnect between the king and the traditional elite of the empire; eunuchs grew unprecedently powerful in his time, being granted large tracts of lands and numerous tax exemptions.

[115] The Assyrian heartland had not been invaded for five hundred years[116] and the event illustrated that the situation was dire enough for Sinsharishkun's closest ally, Psamtik I of Egypt to enter the conflict on Assyria's side.

The massive rise in population in the Assyrian heartland during the height of the Neo-Assyrian Empire might have led to a period of severe drought that affected Assyria to a much larger extent than nearby territories such as Babylonia.

The two Neo-Assyrian kings generally believed to have been usurpers, Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II, did for the most part not mention genealogical connections in their inscriptions but instead relied on direct divine appointment.

The idea of imposing order by creating well-organized hierarchies of power was part of the justifications used by Neo-Assyrian kings for their expansionism: in one of his inscriptions, Sargon II explicitly pointed out that some of the Arab tribes he had defeated had previously "known no overseer or commander".

Occupants of four of the offices, the masennu, nāgir ekalli, rab šāqê and turtanu, are also recorded to have served as governors of important provinces and thus as controllers of local tax revenues and administration.

[164][165] Per estimates by Karen Radner, a message sent from the western border province Quwê to the Assyrian heartland, a distance of 700 kilometers (430 miles) over a stretch of lands featuring many rivers without any bridges, could take less than five days to arrive.

Though most of the preserved sources only give insight into the higher classes of Neo-Assyrian society, the vast majority of the population of the empire would have been farmers who worked land owned by their families.

[180] A consequence of the resettlements, and according to Karen Radner "the most lasting legacy of the Assyrian Empire",[186] was a dilution of the cultural diversity of the Near East, forever changing the region's ethnolinguistic composition and facilitating the rise of Aramaic as the local lingua franca.

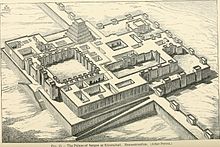

Parks were complex engineering works since they not only exhibited exotic plants from far-away lands but also involved modifying the landscape through adding artificial hills and ponds, as well as pavilions and other small buildings.

Vital, though smaller, hydraulic works also included sewage and drainage systems for buildings which made it possible to dispose of wastewater and efficiently drain the yards, roofs and toilets of not only palaces and temples, but also private homes.

[26] The population of northern Mesopotamia continued to keep the memory of their ancient civilization alive and positively connected with the Assyrian Empire in local histories written as late as the Sasanian period.

[217] Medieval tales written in Aramaic (or Syriac) by and large characterize Sennacherib as an archetypical pagan king assassinated as part of a family feud, whose children convert to Christianity.

[223] The most important innovation in Hebrew theology during the period roughly corresponding to the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire was the elevation of Yahweh as the only god and the beginning of the monotheism that would later characterize Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

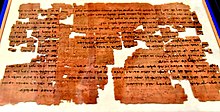

One of the important early figures in Assyrian archaeology was the British business agent Claudius Rich (1787–1821), who visited the site of Nineveh in 1820, traded antiquities with the locals and made precise measurements of the mounds.

Layard was amazed by the ancient Assyrian sites, writing of "mighty ruins in the midst of deserts, defying, by their very desolation and lack of definite form, the description of the traveller".

Layard began his activities in November 1845 at Nimrud (though he believed this to be the site of Nineveh), working as a private individual without any permission to excavate from the Ottoman authorities; he initially tried to fool the local pasha through claiming that he was on a hunting trip.

The idea of continuity between successive empires (a phenomenon in later times dubbed translatio imperii) was a long established tradition in Mesopotamia, going back to the Sumerian King List which connected succeeding and sometimes rival dynasties and kingdoms together as predecessors and successors.

[234] The Biblical Book of Daniel describes a dream of the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II which features a statue with a golden head, silver chest, bronze belly, iron legs and iron/clay feet.

[38] Biblical and other historical reference to Assyrian brutality were reinforced by the 19th-century discoveries of ancient art and inscriptions, as well as by unflattering comparisons drawn between Assyria and the Ottoman Empire by the historians and archaeologists who found them.