Angevin kings of England

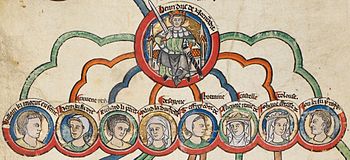

The Angevins (/ˈændʒɪvɪnz/; "of/from Anjou") were a royal house of Anglo-French origin that ruled England and in France in the 12th and early 13th centuries; its monarchs were Henry II, Richard I and John.

Henry II won control of a vast assemblage of lands in western Europe that would last for 80 years and would retrospectively be referred to as the Angevin Empire.

One of many popular theories suggests the blossom of common broom, a bright yellow ("gold") flowering plant, genista in medieval Latin, as the source of the nickname.

The retrospective usage of the name for all of Geoffrey's male-line descendants was popular during the subsequent Tudor dynasty, perhaps encouraged by the further legitimacy it gave to Richard's great-grandson, Henry VIII.

[16][17] The marriage of Count Geoffrey to Matilda, the only surviving legitimate child of Henry I of England, was part of a struggle for power during the tenth and eleventh centuries among the lords of Normandy, Brittany, Poitou, Blois, Maine and the kings of France.

It was from this marriage that Geoffrey's son, Henry, inherited the claims to England, Normandy and Anjou that marks the beginning of the Angevin and Plantagenet dynasties.

[19] As society became more prosperous and stable in the 11th century, inheritance customs developed that allowed daughters (in the absence of sons) to succeed to principalities as well as landed estates.

It is unknown whether King Henry intended to make Geoffrey his heir, but it is known that the threat presented by William Clito's rival claim to the duchy of Normandy made his negotiating position very weak.

[29] In 1162 Theobald, Archbishop of Canterbury, died, and Henry saw an opportunity to re-establish what he saw as his rights over the church in England by appointing his friend Thomas Becket to succeed him.

Henry reacted by getting Becket, and other members of the English episcopate, to recognise sixteen ancient customs—governing relations between the king, his courts, and the church—in writing for the first time in the Constitutions of Clarendon.

When he heard the news, Henry said: "What miserable drones and traitors have I nurtured and promoted in my household who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk."

[30] In 1171, Henry invaded Ireland to assert his overlordship following alarm at the success of knights that he had allowed to recruit soldiers in England and Wales, who had assumed the role of colonisers and accrued autonomous power, including Strongbow.

[46] After re-establishing his authority in England, John planned to retake Normandy and Anjou by drawing the French from Paris while another army (under Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor) attacked from the north.

Many historians use John's death and William Marshall's appointment as protector of nine-year-old Henry III to mark the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty.

This collapse had several causes, including long-term changes in economic power, growing cultural differences between England and Normandy and (in particular) the fragile, familial nature of Henry's empire.

[53] Henry III continued his attempts to reclaim Normandy and Anjou until 1259, but John's continental losses and the consequent growth of Capetian power during the 13th century marked a "turning point in European history".

The retrospective use of the name for Geoffrey's male descendants was popular during the Tudor period, perhaps encouraged by the added legitimacy it gave Richard's great-grandson Henry VIII of England.

[61] The chronicler Gerald of Wales borrowed elements of the Melusine legend to give the Angevins a demonic origin, and the kings were said to tell jokes about the stories.

[63][64] Nevertheless, William of Newburgh, writing after his death, commented that "the experience of present evils has revived the memory of his good deeds, and the man who in his own time was hated by all men, is now declared to have been an excellent and beneficent prince".

[75] Winston Churchill said, "[W]hen the long tally is added, it will be seen that the British nation and the English-speaking world owe far more to the vices of John than to the labours of virtuous sovereigns".

"[81] Eighteenth-century historian David Hume wrote that the Angevins were pivotal in creating a genuinely English monarchy and, ultimately, a unified Britain.

[68] Interpretations of Magna Carta and the role of the rebel barons in 1215 have been revised; although the charter's symbolic, constitutional value for later generations is unquestionable, for most historians it is a failed peace agreement between factions.

[85] Similarly, increased access to contemporary records during the late Victorian era led to a recognition of Henry's contributions to the evolution of English law and the exchequer.

[86][87] He was a bad king: his great exploits, his military skill, his splendour and extravagance, his poetical tastes, his adventurous spirit, do not serve to cloak his entire want of sympathy, or even consideration, for his people.

During the 1950s, Jacques Boussard, John Jolliffe and others focused on the nature of Henry's "empire"; French scholars, in particular, analysed the mechanics of royal power during this period.

[92] Although many of Henry's royal charters have been identified, their interpretation, the financial information in the pipe rolls and broad economic data from his reign has proven more challenging than once thought.

[95] Interest in the morality of historical figures and scholars waxed during the Victorian period, leading to increased criticism of Henry's behaviour and Becket's death.

[101] Jim Bradbury echoes the contemporary consensus that John was a "hard-working administrator, an able man, an able general" with, as Turner suggests, "distasteful, even dangerous personality traits".

The king is a central character in James Goldman's play The Lion in Winter (1966), depicting an imaginary encounter between Henry's family and Philip Augustus over Christmas 1183 at Chinon.

The earliest ballads of Robin Hood such as those compiled in A Gest of Robyn Hode associated the character with a king named "Edward" and the setting is usually attributed by scholars to either the 13th or the 14th century.