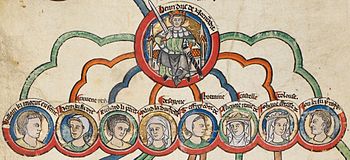

Henry II of England

During his reign he controlled England, substantial parts of Wales and Ireland, and much of France (including Normandy, Anjou, and Aquitaine), an area that altogether was later called the Angevin Empire, and also held power over Scotland and the Duchy of Brittany.

Henry expanded his empire at Louis's expense, taking Brittany and pushing east into central France and south into Toulouse; despite numerous peace conferences and treaties, no lasting agreement was reached.

Several European states allied themselves with the rebels, and the Great Revolt was only defeated by Henry's vigorous military action and talented local commanders, many of them "new men" appointed for their loyalty and administrative skills.

Henry's legal changes are generally considered to have laid the basis for the English Common Law, while his intervention in Brittany, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland shaped the development of their societies, histories, and governmental systems.

[8] After her father's death in 1135, Matilda hoped to claim the English throne, but instead, Stephen was crowned king and recognised as the Duke of Normandy, resulting in a civil war between their rival supporters.

[9] Geoffrey took advantage of the confusion to attack the Duchy of Normandy but played no direct role in the English conflict, leaving this to Matilda and her powerful illegitimate half-brother Robert, Earl of Gloucester.

[23] This time, Henry planned to form a northern alliance with King David I of Scotland, his great-uncle, and Ranulf of Chester, a powerful regional leader who controlled most of the north-west of England.

[37][38][nb 4] In his youth Henry enjoyed active participation in warfare, hunting and other adventurous pursuits; as the years went by he put increasing energy into judicial and administrative affairs and became more cautious, but throughout his life, he was energetic and frequently impulsive.

[39] Despite his surges of anger, he was not normally fiery or overbearing; he was witty in conversation and eloquent in an argument with an intellectual bent of mind and an astonishing memory, and much preferred the solitude of hunting or retiring to his chamber with a book rather than the entertainments of tournaments or troubadours.

[62][57] Henry moved quickly in response, avoiding open battle with Louis in Aquitaine and stabilising the Norman border, pillaging the Vexin and then striking south into Anjou against Geoffrey, capturing one of his main castles, Montsoreau.

[64][65] Bringing only a small army of mercenaries, probably financed with borrowed money, Henry was supported in the north and east of England by the forces of Ranulf of Chester and Hugh Bigod, two local aristocrats, and had hopes of a military victory.

[68] Details of their discussions are unclear, but it appears that the churchmen emphasised that while they supported Stephen as king, they sought a negotiated peace; Henry reaffirmed that he would avoid the English cathedrals and would not expect the bishops to attend his court.

[70] In the face of the increasingly wintry weather, the two men agreed to a temporary truce, leaving Henry to travel north through the Midlands, where the powerful Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, announced his support for the cause.

Louis invariably attempted to take the moral high ground in respect to Henry, capitalising on his own reputation as a crusader and circulating malicious rumours about his rival's ungovernable temper.

[154] Henry controlled more of France than any ruler since the 9th century Carolingians; these lands, combined with his possessions in England, Wales, Scotland and later parts of Ireland, produced a vast domain often referred to by historians as the Angevin Empire.

[186][187] His court attracted huge attention from contemporary chroniclers, and typically comprised several major nobles and bishops, along with knights, domestic servants, prostitutes, clerks, horses and hunting dogs.

[221][222] Indeed, some scholars believe that in most cases he was probably not personally responsible for creating the new processes, but he was greatly interested in the law, seeing the delivery of justice as one of the key tasks for a king and carefully appointing good administrators to conduct the reforms.

[236] The reforms continued and Henry created the General Eyre, probably in 1176, which involved dispatching a group of royal justices to visit all the counties in England over a given period of time, with authority to cover both civil and criminal cases.

[241] In making these reforms Henry both challenged the traditional rights of barons in dispensing justice and reinforced key feudal principles, but over time they greatly increased royal power in England.

According to Edward Grim, an eyewitness to Becket's murder, Henry infamously announced "What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and promoted in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk!

[350] This policy proved unsuccessful, as Ua Conchobair was unable to exert sufficient influence and force in areas such as Munster: Henry instead intervened more directly, establishing a system of local fiefs of his own through a conference held in Oxford in 1177.

William's campaign began to falter as the Scots failed to take the key northern royal castles, in part due to the efforts of Henry's illegitimate son, Geoffrey.

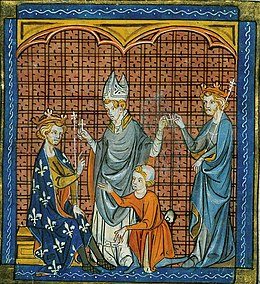

[375] Henry travelled to Becket's tomb in Canterbury, where he announced that the rebellion was a divine punishment on him, and did appropriate penance; this made a major difference in restoring his royal authority at a critical moment in the conflict.

[392] In the late 1170s, Henry focused on trying to create a stable system of government, increasingly ruling through his family, but tensions over the succession arrangements were never far away, ultimately leading to a fresh revolt.

[413] Initially Henry and Philip Augustus had enjoyed a good relationship, and they agreed to a joint alliance, even though this cost the French king the support of Flanders and Champagne.

This collapse had various causes, including long-term changes in economic power, growing cultural differences between England and Normandy, the military shortcomings of King John, but in particular the fragile, familial nature of Henry's empire.

[441] William of Newburgh, writing in the next generation, commented that "the experience of present evils has revived the memory of his good deeds, and the man who in his own time was hated by all men, is now declared to have been an excellent and beneficent prince".

[443] In the Victorian period there was a renewed interest in the personal morality of historical figures, and scholars began to express greater concern over aspects of Henry's behaviour, including his role as a parent and husband.

[445] Late-Victorian historians, with increasing access to the documentary records from the period, stressed Henry's contribution to the evolution of key English institutions, including the development of the law and the exchequer.

[453][454] Although many more of Henry's royal charters have been identified, the task of interpreting these records, the financial information in the pipe rolls and wider economic data from the reign is understood to be more challenging than once thought.