Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan

"[1] He felt it was necessary to avoid "being driven into premature action by the small but influential section of public opinion which persistently and strenuously advocated the cause of immediate reconquest."

[5] After Adwa the Italian government appealed to Britain to create some kind of military diversion to prevent Mahdist forces from attacking their isolated garrison at Kassala, and on 12 March the British cabinet authorised an advance on Dongola for this purpose.

[6] The French government had in fact just dispatched Jean-Baptiste Marchand up the Congo River with the stated aim of reaching Fashoda on the White Nile and claiming it for France.

This encouraged the British to attempt the full-scale defeat of the Mahdist State and the restoration of Anglo-Egyptian rule, rather than just providing a military diversion as Italy had requested.

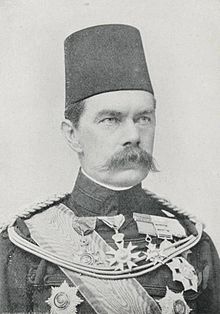

As Governor-General of Suakin from 1886 to 1888, Kitchener had held off the Mahdist forces under Osman Digna from the Red Sea coast,[8] but he had never commanded a large army in battle.

[5] The Egyptian army mobilised and by 4 June 1896 Kitchener had assembled a force of 9,000 men, consisting of ten infantry battalions, fifteen cavalry and camel corps squadrons, and three artillery batteries.

[11] The Egyptian army in the 1880s was consciously trying to distance itself from the times of Muhammad Ali, when Sudanese men had been captured, enslaved, shipped to Egypt and enlisted.

[12] While no official requirement existed for the practice, it is clear that in many instances at least, new Sudanese recruits into the Egyptian army were branded by their British officers, to help identify deserters and those discharged seeking to re-enlist.

The 230 miles of railway reduced the journey time between Wadi Halfa and Abu Hamad from 18 days by camel and steamer to 24 hours by train, all year round, regardless of the season and the flooding of the Nile.

[18] Later, when the line was extended towards Atbara, Kitchener was able to transport three heavily armed gunboats in sections to be reassembled at Abadieh, enabling him to patrol and reconnoitre the river up to the sixth cataract.

The village was a Mahdist strongpoint some way upriver from Akasha; its commanders, Hammuda and Osman Azraq, led around 3,000 soldiers and had evidently decided to hold his ground rather than withdraw as the Egyptian army advanced.

[19] At dawn on 7 June, two Egyptian columns attacked the village from north and south, killing 800 Mahdist soldiers, with others plunging naked into the Nile to make their escape.

This left the road to Dongola clear, but despite advice to move rapidly and take it, Kitchener adhered to his usual cautious and carefully prepared approach.

[20] The Egyptian river navy consisted of the gunboats Tamai, El Teb, Metemma and Abu Klea as well as the steamers Kaibar, Dal and Akasha.

Dongola was defended by a substantial Mahdist force under the command of Wad Bishara, consisting of 900 jihadiyya, 800 Baqqara Arabs, 2,800 spearmen, 450 camel and 650 horse cavalry.

Kitchener was unable to advance on Dongola immediately after the Battle of Farka because not long afterwards, cholera broke out in the Egyptian camp, and killed over 900 men in July and early August 1896.

He also ordered Osman Digna in eastern Sudan and his commanders in Kordofan and other regions to bring their forces in to Omdurman, strengthening its defences with some 150,000 additional fighters.

Their chief, Abdallah wad Saad, therefore wrote to Kitchener on 24 June, pledging the loyalty of his people to Egypt and asking for men and weapons to assist them against the Khalifa.

[27] The sudden advance of the river force and uncertainty about whether he would be reinforced by the Kordofan Army prompted the Mahdist commander in Berber, Zeki Osman, to abandon the town on 24 August, and it was occupied by the Egyptians on 5 September.

As the Red Sea area returned its loyalty to Egypt, an Egyptian force also marched from Suakin to retake Kassala, which had been temporarily occupied by the Italians since 1893.

[28] For the remainder of the year Kitchener extended the railway line forward from Abu Hamad, built up his forces in Berber, and fortified the north bank of the confluence with the Atbarah River.

Meanwhile, the Khalifa strengthened the defences of Omdurman and Metemma and prepared an attack on the Egyptian positions while the river was low and the gunboats could neither retreat below the fifth cataract nor advance above the sixth.

[29] To be sure he had the necessary strength to defeat the Mahdist forces in their heartland, Kitchener brought up reinforcements from the British Army, and a brigade under Major General William F. Gatacre arrived in Sudan at the end of January 1898.

[30] Skirmishes took place in the early Spring, as the Mahdist forces made an attempt in March to outflank Kitchener by crossing the Atbara, but they were outmaneuvered; the Egyptians steamed upstream and raided Shendi.

Eventually, at dawn on 8 April, the Anglo-Egyptians mounted a full frontal assault on the forces of Osman Digna with three infantry brigades, holding one in reserve.

In February 1899, Kitchener responded to criticisms by categorically denying that he had ordered or permitted the Mahdist wounded in the battlefield to be massacred by his troops; that Omdurman had been looted; and that civilian fugitives in the city had been deliberately fired on.

Gallabat was reoccupied on 7 December, although the two Ethiopian flags that had been raised there after the Mahdist evacuation were left flying pending instructions from Cairo.

Despite the easy recovery of these key towns there remained a great deal of fear and confusion in the countryside across the Jezirah, where bands of Mahdist supporters continued to roam, pillaging and killing for several months after the fall of Omdurman.

The newly established Anglo-Egyptian government in Khartoum did not attempt to reconquer the far western territory of Darfur, which the Egyptians had held only briefly between 1875 and the surrender of Slatin Pasha in 1883.