Mahdist War

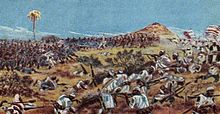

Allied victory British-Egyptian expeditions (1885–1889) Ethiopian campaigns (1885–1889) Italian campaigns (1890–1894) British-Egyptian reconquest (1896–1899) The Mahdist War[b] (Arabic: الثورة المهدية, romanized: ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese, led by Muhammad Ahmad bin Abdullah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided One"), and the forces of the Khedivate of Egypt, initially, and later the forces of Britain.

After four years of revolt, the Mahdist rebels overthrew the Ottoman-Egyptian administration with the fall of Khartoum and gained control over Sudan.

Throughout the period of Egyptian rule, many segments of the Sudanese population suffered extreme hardship because of the system of taxation imposed by the central government.

Fearing the brutal and unjust methods of the Sha'iqiyya, many farmers fled their villages in the fertile Nile Valley to the remote areas of Kordofan and Darfur.

These migrants, known as "jallaba" after their loose-fitting style of dress, began to function as small traders and middlemen for the foreign trading companies that had established themselves in the cities and towns of central Sudan.

With Khedive Ismail's spending and corruption causing instability, in 1873 the British government supported a program whereby an Anglo-French debt commission assumed responsibility for managing Egypt's fiscal affairs.

This commission eventually forced Khedive Ismail to abdicate in favor of his son Tawfiq in 1879, leading to a period of political turmoil.

[citation needed] Although the Egyptians were fearful of the deteriorating conditions, the British refused to get involved, as Foreign Secretary Earl Granville declared, "Her Majesty’s Government are in no way responsible for operations in the Sudan".

[11] In the 1870s, a Muslim cleric named Muhammad Ahmad preached renewal of the faith and liberation of the land, and began attracting followers.

This movement, posed as a triumphant progress, incited many of the Arab tribes to rise in support of the Jihad the Mahdi had declared against the Egyptian government.

In mid-1882, this force approached the Mahdist gathering, whose members were poorly clothed, half starving, and armed only with sticks and stones.

The force was, in the words of Winston Churchill, "perhaps the worst army that has ever marched to war"[19]—unpaid, untrained, and undisciplined, its soldiers having more in common with their enemies than with their officers.

Upon his approach, the Mahdi assembled an army of about 40,000 men and drilled them rigorously in the art of war, equipping them with the arms and ammunition captured in previous battles.

The withdrawal of the Egyptian garrisons stationed throughout the country, such as those at Sennar, Tokar and Sinkat, was therefore threatened unless it was conducted in an orderly fashion.

It was hoped that Mahdist forces would judge an attack on a British subject to be too great a risk, and hence allow the withdrawal to proceed without incident.

However, he was also renowned for his aggression and rigid personal honour,[24] which, in the eyes of several prominent British officials in Egypt, made him unsuitable for the task.

Sir Evelyn Baring was particularly opposed to Gordon's appointment, but was overruled by Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Earl Granville.

Gordons orders were: 1) to evacuate all Egyptian garrisons from Sudan (including both soldiers and civilians) and 2) to leave some form of indigenous (but not Mahdist) government behind him.

Gordon had enthusiastically supported the idea of recalling the notorious former slaver Al-Zubayr Rahma from exile in Egypt to organize and lead a popular uprising against the Mahdi.

An expedition was duly dispatched under Sir Garnet Wolseley, but as the level of the White Nile fell through the winter, muddy 'beaches' at the foot of the walls were exposed.

The British Government, under strong pressure from the public reluctantly sent a relief column under Sir Garnet Wolseley to relieve the Khartoum garrison.

The British also sent an expeditionary force under Lieutenant-General Sir Gerald Graham, including an Indian contingent, to Suakin in March 1885.

In September 1884, Ethiopia reoccupied the province of Bogos, which had been occupied by Egypt, and began a long campaign to relieve the Egyptian garrisons besieged by the Mahdists.

In January 1886, a Mahdist army invaded Ethiopia, seized Dembea, burned the Mahbere Selassie monastery and advanced on Chilga.

Lord Cromer, judging that the Conservative-Unionist government in power would favour taking the offensive, managed to extend the demonstration into a full-fledged invasion.

Their advance was slow and methodical, while fortified camps were built along the way, and two separate 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) Narrow gauge railways were hastily constructed from a station at Wadi Halfa: the first rebuilt Isma'il Pasha's abortive and ruined former line south along the east bank of the Nile to supply the 1896 Dongola Expedition[c] and a second, carried out in 1897, was extended along a new line directly across the desert to Abu Hamad—which they captured in the Battle of Abu Hamed on 7 August 1897[54]—to supply the main force moving on Khartoum.

[52][53] It was not until 7 June 1896 that the first serious engagement of the campaign occurred, when Kitchener led a 9,000 strong force that wiped out the Mahdist garrison at Ferkeh.

As a result, textile items like these make up a large portion of the booty which was taken back to Britain after the British victory over the Mahdist forces at the Battle of Omdurman in 1899.

[58] The flags were colour coded to direct soldiers of the three main divisions of the Mahdist army – the Black, Green and Red Banners (rāyāt).

The decision to adopt the religious garment as military dress enforced unity and cohesion among his forces, and eliminated traditional visual markers differentiating potentially fractious tribes.