Anglo-Japanese style

The style was popularised by Edward William Godwin in the 1870s in England, with many artisans working in the style drawing upon Japan as a source of inspiration and designed pieces based on Japanese Art, whilst some favoured Japan simply for its commercial viability, particularly true after the 1880s when the British interest in Eastern design and culture is regarded as a characteristic of the Aesthetic Movement.

Bornemann & Co of Bath, and described (and possibly designed) by Christopher Dresser as the quaint and unique Japanese character, to be the first documented piece of furniture in the Anglo-Japanese style.

'Ornament' referring to an important aspect of English architectural decorative design for the period, deriving from the popular ornamentation at the time found on the exterior of European churches, and placing this beside nature.

In the White House in Chelsea, he organised the furniture to be distributed asymmetrically, and the walls to covered in gold leaf inspired by Japanese design and interiors.

[20][30] Dante saw the refinement of line in Japanese arts as having "nothing to ask of European attainment or models; it is an integral organism ... [being in its accuracy and finesse] more instinctive than the artists of other races.

[27] Early in the decade, the Watcombe pottery in Devon produced unglazed terracotta wares, some of which rely entirely on Japanese forms and the natural colour of the clay for their ornamental effect.

In the same year, Thomas Edward Collcutt began designing a number of Japanese inspired ebonized sideboards, cabinets and chairs for Collinson & Lock.

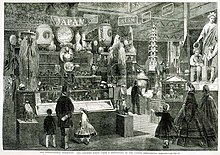

[39] Augustus Wollaston Franks set up an exhibition of ceramics, mainly porcelain, at the Bethnal Green Museum in 1876; having collected netsuke and tsuba from Japan.

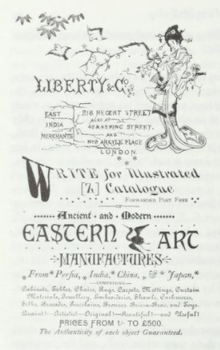

Godwin in the British Architect reported that Liberty's [has] Japanese papers for the walls; curtain stuffs for windows and doors; folding screens, chairs, stools [etc.

In 1878, Daniel Cottier finished a series of stained glass window panels Morning Glories which detail 'a lattice fence ... which adapt from a variety of Japanese ... screens, textile stencils, manga and ukiyo-e prints'.

[41] Indeed, Cottier ( a Glaswegian who worked in London and New York City) had his Studio and shop full of Aesthetic and Anglo-Japanese ebonised-wood furniture, his Studio producing through his apprentice Stephen Adam until the 1880s a number of Japanese decorative carpentry pieces, frequently using dark woods and gold floral Chrysanthemum accents, all popular Japanese motifs amongst westerners produced for the Western markets.

James Lamb (cabinetmaker) and Henry Ogden & Sons also began making Anglo-Japanese furniture for the western market such as hanging cabinets and tables and chairs.

He also produced a number of aesthetical wallpapers in the style for Warner and Ramm, notably 'characteristic [using] Japanese simplicity of line and colour' drawn from the aesthetial practices taught in the works of Dresser and Godwin.

[49] As aestheticism began to grow more popular, designers found the 'cult of personality, particularly when it involved creators of art, fundamentally conflicted with Ruskin's and Morris's emphasis upon the importance of traditional craftsman and artisans.'

[52] Stevens & Williams then in 1884 began to make their 'Matsu-no-Kee' decorative glass and fairy bowls, which took on the simplified nature so prominent amongst the Anglo-Japanese style and from the bright colour schemes seen in contemporary woodblock prints.

[53] Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo also began designing furniture inspired by Ikebana, as was noted further by many periodicals in the time on the subject of Japanese flower arrangement.

[55] Alfred East is commissioned by the Fine Art Society to paint in Japan for six months in 1888, and Frank Morley Fletcher becomes introduced to Japanese woodcuts, helping through the next 22 years to teach about them in London and Reading, Yorkshire.

[59] Menpes issued an Osaka-based Japanese company to furnish his home with stained curved wood panelling, traditionally seen in Shiro interiors or cornicing with gold detailing; based on Japanese lacquer, installed Kunmiko Ramma (decorative latticed ventilation screens), double-sided Anglo-Japanese window frames and employed typical minimal decoration.

One notable example from the decade of the move into the modern style includes Aubrey Beardsley, who intertwined the influence of what was termed in England the Modern Style with Japanese woodblock prints (such as Hokusai's Manga, made from 1814 to 1878) to form an English adaptation of the 'grotesque effects which the Japanese convention allowed' of presenting illustration in the Salome (1893) and The Yellow Book (1894–1897), particularly his 'Bon-Mots of Sydney Smith' (1893) illustrations.

He was known to have received a copy of shunga by the artist Utamaro from William Rothenstein which heavily influenced Beardsley's own erotic imagery, being first introduced to Japanese woodblock prints during his lunch hours working in Frederick Evan's Holborn bookstore circa 1889.

[18] Charles Ricketts also showcased the influence of Japanese line art in Wilde's 1891 House of Pomegranates which used Peacock and crocus blooms which 'appear in uniform rows like a repeated wallpaper pattern' (such as in the aesthetical merit of Voysey) and the 'asymmetrical construction of the page [, bookcover and illustration]' design; drawing also from nature; and in his proportions for the 1894 Wilde publication of the Sphinx which also predated the early form of English-Japanese influences of the Modern Style.

In 1902, with the signing of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, Japan gained great power status in the eyes of British foreign policy-makers and along with 'progressive' industrialisation, Japanese influence became more pronounced, particularly with regard to the ship building industry in Glasgow.

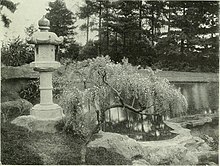

Common elements include 'stone lanterns, the use of large rocks and pebbles, stone bowls of water, and decorative shrubs and flowers like acers, azaleas and lilies' and 'red painted bridges'.

'[82] Roger Fry also noted how European artists had begun to forget Chiaroscuro in favour of the Eastern style of what Binyon termed sensuosness; or the 'rejection of light and shade'.

1910–1925) also designed a number of blue Titianian Vases decorated in Anglo-Japanese motifs such as the Red-crowned crane or Peacock and Matsu pine leaves for Royal Doulton.

'[87] My chief concern has been, not to discuss questions of authorship or archaeology, but to inquire what aesthetic value and significance these Eastern paintings possess for us in the West – Binyon (1913)With the advent of the further academic understanding of Japanese aesthetics, the Anglo-Japanese style ended, morphing into Modernism with the death of the 'Japan Craze' and Japanese art objects having become permanent parts of European and American Museum collections.

In 1911, Frank Brangwyn had begun to collaborate with various Japanese artists such as Ryuson Chuzo Matsuyama working in Edwardian England on woodblock printing techniques.

[98] Notably, 'Japan has played an important role in triggering [the] ideas of modernism, when [Mackintosh also] attracted most attention' at the turn of the 20th century in his designs in Continental Europe.

[96][99] In the United States, early appreciation of the Anglo-Japanese style was also transferred over in the posthumous publications of Charles Locke Eastlake's Hints on Household Taste (first published in 1868).

[101] Some of the glass and silverwork by Louis Comfort Tiffany, textiles and wallpaper by Candace Wheeler, and the furniture of Kimbel & Cabus, Daniel Pabst, Nimura & Sato, and the Herter Brothers (particularly that produced after 1870) shows influence of the Anglo-Japanese style.