Anglo-Saxon architecture

Generally preferring not to settle within the old Roman cities, the Anglo-Saxons built small towns near their centres of agriculture, at fords in rivers or sited to serve as ports.

In recent decades, architectural historians have become less confident that all undocumented minor "Romanesque" features post-date the Norman Conquest.

Only ten of the hundreds of settlement sites that have been excavated in England from this period have revealed masonry domestic structures and confined to a few quite specific contexts.

Le Goff suggests that the Anglo-Saxon period was defined by its use of wood,[2] providing evidence for the care and craftsmanship that the Anglo–Saxon invested into their wooden material culture, from cups to halls, and the concern for trees and timber in Anglo–Saxon place–names, literature and religion.

Unlike in the Carolingian world, late Anglo–Saxon royal halls continued to be of timber in the manner of Yeavering centuries before, even though the king could clearly have mustered the resources to build in stone.

[8] Even the elite had simple buildings, with a central fire and a hole in the roof to let the smoke escape and the largest of which rarely had more than one floor, and one room.

[13] There is a reconstruction of an Anglo-Saxon settlement at West Stow in Suffolk, and contemporary illustrations of both secular and religious buildings are sometimes found in illuminated manuscripts.

The fall of Roman Britain at the beginning of the fifth century, according to Bede, allowed an influx of invaders from northern Germany including the Angles and Saxons.

In 597, the mission of Augustine from Rome came to England to convert the southern Anglo-Saxons, and founded the first cathedral and a Benedictine monastery at Canterbury.

In 664 a synod was held at Whitby, Yorkshire, and differences between the Celtic and Roman practices throughout England were reconciled, mostly in favour of Rome.

The Romano-British populations of Wales, the West Country, and Cumbria experienced a degree of autonomy from Anglo-Saxon influence,[15] represented by distinct linguistic, liturgical and architectural traditions, having much in common with the Irish and Breton cultures across the Celtic Sea, and allying themselves with the Viking invaders.

Characteristically circular buildings[16] as opposed to rectangular, often in stone as well as timber, along with sculptured Celtic crosses, holy wells and the reoccupation of Iron Age and Roman sites from hillforts such as Cadbury Castle, promontory hillforts such as Tintagel, and enclosed settlements called Rounds[17] characterise the western Sub-Roman Period up to the 8th century in southwest England[16] and continue much later in independent Wales at post-Roman cities such as Caerleon and Carmarthen.

Subsequent Danish (Viking) invasion marked a period of destruction of many buildings in England, including in 793 the raid on Lindisfarne.

Oxford is an example of one of these fortified towns, where the eleventh-century stone tower of St Michael's Church has prominent position beside the former site of the North gate.

The building of church towers, replacing the basilican narthex or West porch, can be attributed to this late period of Anglo-Saxon architecture.

The earliest surviving Anglo-Saxon architecture dates from the 7th century, essentially beginning with Augustine of Canterbury in Kent from 597; for this he probably imported workmen from Frankish Gaul.

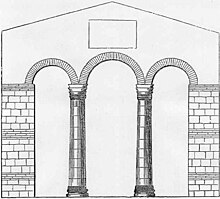

The cathedral and abbey in Canterbury, together with churches in Kent at Minster in Sheppey (c.664) and Reculver (669), and in Essex at the Chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall at Bradwell-on-Sea (where only the nave survives), define the earliest type in southeast England.

Developments in design and decoration may have been influenced by the Carolingian Renaissance on the continent, where there was a conscious attempt to create a Roman revival in architecture.

A number of early Anglo-Saxon churches are based on a basilica with north and south porticus (projecting chambers) to give a cruciform plan.