Buildings and architecture of Brighton and Hove

[2] Brighton's transformation from medieval fishing village into spa town and pleasure resort, patronised by royalty and fashionable high society, coincided with the development of Regency architecture and the careers of three architects whose work came to characterise the 4-mile (6.4 km) seafront.

The previously separate village of Hove developed as a comfortable middle-class residential area "under a heavy veneer of [Victorian] suburban respectability":[3] large houses spread rapidly across the surrounding fields during the late 19th century, although the high-class and successful Brunswick estate was a product of the Regency era.

Old villages such as Portslade, Rottingdean, Ovingdean and Patcham, with ancient churches, farms and small flint cottages, became suburbanised as the two towns grew and merged, and the creation of "Greater Brighton" in 1928 brought into the urban area swathes of open land which were then used for housing and industrial estates.

Next came Palmeira Square (c. 1855–1865), where the evolution from Regency to Victorian Italianate is clear,[52] and there was some suburban development (called Cliftonville) around the new Hove railway station in the 1860s, but large tracts of land to the north and west remained undeveloped because of conditions in William Stanford's will.

[68][69] Praise from the Architects' Journal was matched by Alderman Sir Herbert Carden, who campaigned for every other building along the seafront to be demolished and replaced with Embassy Court-style Modernist structures, all the way from Hove to Kemp Town.

Black glazed mathematical tiles and bungaroosh are unique to Brighton and its immediate surroundings,[97] and tarred cobblestones with brick quoins, salt-glazed brickwork and knapped or plain flints were also common in early buildings.

Nearly 90% of its materials—from the timber-framed structure (made of reclaimed wood from building sites) and exterior walls formed of waste chalk and clay to the household-rubbish insulation (VHS cassettes, toothbrushes and denim offcuts)—were destined for landfill.

[121][122][123] Concrete and steel framing became common in the 20th century: examples include the new Hove Town Hall, Brighton's police station and courthouse,[LLB 1] and the original Churchill Square shopping centre.

[129] The Queen Anne Revival-style housing popular in Hove in the late 19th century[53] had its own window pattern: two-part sashes with many panes on the upper section, separated by wider glazing bars than those used in earlier years.

[88] In 1976–77, old council houses in the Ingram Crescent area off Portland Road were replaced by low-rise flats in a modern style with varied architectural features such as weatherboarding-style timber, dark brickwork and catslide roofs.

[147] The fields around the ancient village of Hove were owned by a few large landholders, whose gradual release of land for development in the 19th and early 20th centuries contributed to the town's distinctive pattern of growth: individual architects or firms designed small estates with a homogeneous overall style but with much variation between them.

King George VI Mansions[LLB 1] at West Blatchington consist of three long groups of three-storey brick and tile terraces forming a quadrangle around an area of open space; designed by T. Garratt and Sons in the "Vernacular Revival" style, they are little changed since their construction.

Most were demolished in the 1960s and 1970s, and the large warehouses of the Fairway Trading Estate occupy the Moulsecoomb site; but the company's wide brown-brick administrative and design office, built in 1966 on Lewes Road, was sold to Brighton Polytechnic and became Mithras House.

Harry Stuart Goodhart-Rendel's widely praised St Wilfrid's Church of 1932–34 (closed 1980), which embraced architectural Eclecticism and Rationalism, used two-tone brick and reinforced concrete and had an unusual interior layout designed to make the altar highly visible.

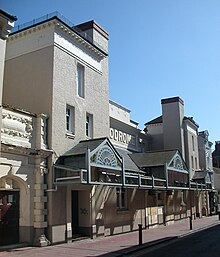

Bryan Graham of architecture firm Nightingale Associates designed the facility, which is distinguished by a right-oriented round tower, several curved windows with decorative panels of opaque glass, and six-panelled doors.

The former John Nixon Memorial Hall[LLB 1] of 1912, by an unknown architect, contrasts with Kemptown's small-scale stuccoed terraces with its broad arched-windowed, red-brick façade and the Neo-Jacobean free-style treatment of its gabled roofline.

[261] On the West Brighton estate, Samuel Denman's Grade II-listed Hove Club (1897) is another Jacobean-style red-brick building with prominent gables, which also features buttresses rising to form chimneys, a loggia entrance, stone mullions and transoms, Art Nouveau-style windows and ornate interior timberwork.

Designed by Samuel Bridgman Russell in 1911–12, in a Neo-Georgian/Queen Anne style with extensive red brickwork and wings joined to a central section by a series of staircases lit by round windows), it occupies a prominent corner site and retains its original iron gates with the emblems of Hove and Brighton Boroughs and East and West Sussex.

[283][Note 4] Anthony Carneys' design for the new Aldrington Church of England Primary School (1991) consisted of a "cluster of buildings with a Dutch barn feel to the roofline" and a rural ambience, despite the urban location.

[316] John Leopold Denman transformed the Freemasons Tavern in Brunswick Town from a Classical-style mid 19th-century pub, similar to its neighbours, into a spectacularly elaborate restaurant with an ornately moulded Art Deco interior and a blue and gold mosaic exterior with Masonic imagery and bronze fittings.

[Note 5] Many Portsmouth & Brighton United Breweries pubs have green tiled façades and leadlights, including the Horse and Groom (Hanover), the Long Man of Wilmington (Patcham), the Montreal Arms (Carlton Hill) and the Heart and Hand (North Laine).

[286] Bandstands, elaborately roofed kiosks, shelters with decorative awnings, pale green railings and tall, ornate lamp-posts are found regularly along the whole seafront; most structures date from the late 19th century[286] and many are Grade II-listed.

The 21-bay double-aisled interior remains as built, but of his High Victorian Gothic-style work on the exterior only an "attention-seeking clock tower" survives,[Note 7] because the building was revamped in 1927–29 by the Borough Surveyor David Edwards.

[335] Brighton Marina at Black Rock dates from 1971–76 and has little architectural interest:[89] an "insipid neo-Regency" pastiche style was used for many of the residential buildings, and the wide range of commercial premises are dominated by a vast supermarket.

[349] The Grade II*-listed London Road viaduct (1846) by John Urpeth Rastrick used 10 million yellow and red bricks, spectacularly spanned the undeveloped valley until terraced houses crowded round it, and made it possible for the LBSCR to reach Lewes and Newhaven.

[159][361][367] Francis May's "pompous"[368] clock tower, built in the newly laid out Preston Park in 1891–92, also combined some Classical and Gothic elements—this time using terracotta, pale brick and stone—but its style is closest in spirit to Neo-Flemish Renaissance.

[362][368] A London architect, Llewellyn Williams, won the commission for the Queen's Park clock tower in 1915; his three-stage design, on high ground, incorporates Portland stone (partly rusticated) and red brick, and also has a copper roof.

[38] The Royal Suspension Chain Pier (1822–23, by Captain Samuel Brown rn) became Brighton's first "effective focal point" after it became a fashionable seaside resort,[98] but demolition was already under consideration by the time it was destroyed by a storm in 1896.

An especially infamous incident occurred in 1971, when Stroud and Mew's "Regency Gothic" Central National School in North Laine was knocked down[385] hours before its listed status was granted: the letter was apparently delayed by a postal strike.

Failure to do so can result in an unlimited fine, 12 months' imprisonment, or both.Buildings listed at Grade I include the Royal Pavilion, Stanmer House, several churches, the wrecked West Pier, the main building at the University of Sussex and the principal parts of the Kemp Town and Brunswick estates.