Angular momentum operator

The angular momentum operator plays a central role in the theory of atomic and molecular physics and other quantum problems involving rotational symmetry.

In quantum mechanics, angular momentum can refer to one of three different, but related things.

In the special case of a single particle with no electric charge and no spin, the orbital angular momentum operator can be written in the position basis as:

, which combines both the spin and orbital angular momentum of a particle or system:

For example, the spin–orbit interaction allows angular momentum to transfer back and forth between L and S, with the total J remaining constant.

For electronic singlet states the rovibronic angular momentum is denoted J rather than N. As explained by Van Vleck,[7] the components of the molecular rovibronic angular momentum referred to molecule-fixed axes have different commutation relations from those given above which are for the components about space-fixed axes.

Like any vector, the square of a magnitude can be defined for the orbital angular momentum operator,

This inequality is also true if x, y, z are rearranged, or if L is replaced by J or S. Therefore, two orthogonal components of angular momentum (for example Lx and Ly) are complementary and cannot be simultaneously known or measured, except in special cases such as

In this case the quantum state of the system is a simultaneous eigenstate of the operators L2 and Lz, but not of Lx or Ly.

In the Schroedinger representation, the z component of the orbital angular momentum operator can be expressed in spherical coordinates as,[15]

are restricted to integers, unlike the quantum numbers for the total angular momentum

[17] An alternative derivation which does not assume single-valued wave functions follows and another argument using Lie groups is below.

[18] This was recognised by Pauli in 1939 (cited by Japaridze et al[19]) ... there is no a priori convincing argument stating that the wave functions which describe some physical states must be single valued functions.

[20][21] These do not behave well under the ladder operators, but have been found to be useful in describing rigid quantum particles[22] Ballentine[23] gives an argument based solely on the operator formalism and which does not rely on the wave function being single-valued.

(Dimensional correctness may be maintained by inserting factors of mass and unit angular frequency numerically equal to one.)

But the two terms on the right are just the Hamiltonians for the quantum harmonic oscillator with unit mass and angular frequency

A more complex version of this argument using the ladder operators of the quantum harmonic oscillator has been given by Buchdahl.

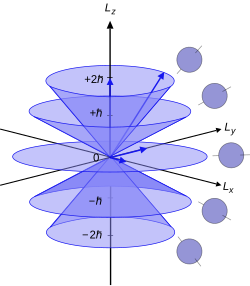

[25] Since the angular momenta are quantum operators, they cannot be drawn as vectors like in classical mechanics.

are unknown; therefore every classical vector with the appropriate length and z-component is drawn, forming a cone.

The expected value of the angular momentum for a given ensemble of systems in the quantum state characterized by

The quantization rules are widely thought to be true even for macroscopic systems, like the angular momentum L of a spinning tire.

is roughly 100000000, it makes essentially no difference whether the precise value is an integer like 100000000 or 100000001, or a non-integer like 100000000.2—the discrete steps are currently too small to measure.

For most intents and purposes, the assortment of all the possible values of angular momentum is effectively continuous at macroscopic scales.

[26] The most general and fundamental definition of angular momentum is as the generator of rotations.

The existence of the generator is guaranteed by the Stone's theorem on one-parameter unitary groups.

In simpler terms, the total angular momentum operator characterizes how a quantum system is changed when it is rotated.

The ladder operator derivation above is a method for classifying the representations of the Lie algebra SU(2).

By carefully analyzing this noncommutativity, the commutation relations of the angular momentum operators can be derived.

For a particle without spin, J = L, so orbital angular momentum is conserved in the same circumstances.

When the spin is nonzero, the spin–orbit interaction allows angular momentum to transfer from L to S or back.

- The operator R , related to J , rotates the entire system.

- The operator R spatial , related to L , rotates the particle positions without altering their internal spin states.

- The operator R internal , related to S , rotates the particles' internal spin states without changing their positions.