Kinetic energy

[1] In classical mechanics, the kinetic energy of a non-rotating object of mass m traveling at a speed v is

[2] The kinetic energy of an object is equal to the work, or force (F) in the direction of motion times its displacement (s), needed to accelerate the mass from rest to its stated velocity.

The adjective kinetic has its roots in the Greek word κίνησις kinesis, meaning "motion".

[3] The principle of classical mechanics that E ∝ mv2 is conserved was first developed by Gottfried Leibniz and Johann Bernoulli, who described kinetic energy as the living force or vis viva.

By dropping weights from different heights into a block of clay, Gravesande determined that their penetration depth was proportional to the square of their impact speed.

[5] The terms kinetic energy and work in their present scientific meanings date back to the mid-19th century.

Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis published in 1829 the paper titled Du Calcul de l'Effet des Machines outlining the mathematics of kinetic energy.

William Thomson, later Lord Kelvin, is given the credit for coining the term "kinetic energy" c.

On a level surface, this speed can be maintained without further work, except to overcome air resistance and friction.

For example, the cyclist could encounter a hill just high enough to coast up, so that the bicycle comes to a complete halt at the top.

Alternatively, the cyclist could connect a dynamo to one of the wheels and generate some electrical energy on the descent.

Another possibility would be for the cyclist to apply the brakes, in which case the kinetic energy would be dissipated through friction as heat.

In an entirely circular orbit, this kinetic energy remains constant because there is almost no friction in near-earth space.

Disregarding loss or gain however, the sum of the kinetic and potential energy remains constant.

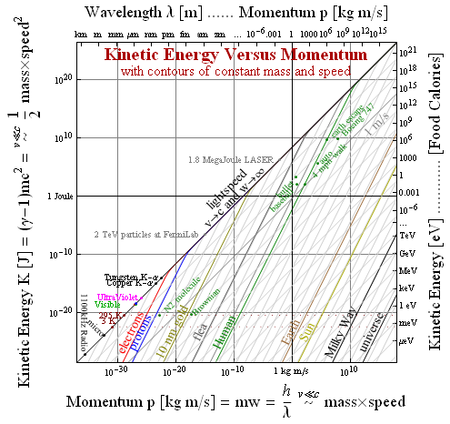

For objects and processes in common human experience, the formula 1/2mv2 given by classical mechanics is suitable.

Treatments of kinetic energy depend upon the relative velocity of objects compared to the fixed speed of light.

In SI units, mass is measured in kilograms, speed in metres per second, and the resulting kinetic energy is in joules.

For example, one would calculate the kinetic energy of an 80 kg mass (about 180 lbs) traveling at 18 metres per second (about 40 mph, or 65 km/h) as

The kinetic energy of a moving object is equal to the work required to bring it from rest to that speed, or the work the object can do while being brought to rest: net force × displacement = kinetic energy, i.e.,

For example, a car traveling twice as fast as another requires four times as much distance to stop, assuming a constant braking force.

Since this is a total differential (that is, it only depends on the final state, not how the particle got there), we can integrate it and call the result kinetic energy:

A macroscopic body that is stationary (i.e. a reference frame has been chosen to correspond to the body's center of momentum) may have various kinds of internal energy at the molecular or atomic level, which may be regarded as kinetic energy, due to molecular translation, rotation, and vibration, electron translation and spin, and nuclear spin.

The speed, and thus the kinetic energy of a single object is frame-dependent (relative): it can take any non-negative value, by choosing a suitable inertial frame of reference.

In any other case, the total kinetic energy has a non-zero minimum, as no inertial reference frame can be chosen in which all the objects are stationary.

This minimum kinetic energy contributes to the system's invariant mass, which is independent of the reference frame.

The kinetic energy of the system in the center of momentum frame is a quantity that is invariant (all observers see it to be the same).

The mathematical by-product of this calculation is the mass–energy equivalence formula, that mass and energy are essentially the same thing:[14]: 51 [15]: 121

When objects move at a speed much slower than light (e.g. in everyday phenomena on Earth), the first two terms of the series predominate.

This can also be expanded as a Taylor series, the first term of which is the simple expression from Newtonian mechanics:[16] This suggests that the formulae for energy and momentum are not special and axiomatic, but concepts emerging from the equivalence of mass and energy and the principles of relativity.

This means clocks run slower and measuring rods are shorter near massive bodies.