Aṅgulimāla

In an attempt to get rid of Aṅgūlimāla, the teacher sends him on a deadly mission to find a thousand human fingers to complete his studies.

Moreover, Aṅgulimāla's story is referred to in scholarly discussions of justice and rehabilitation, and is seen by theologian John Thompson as a good example of coping with moral injury and an ethics of care.

[5] Two texts in the early discourses in the Pāli language are concerned with Aṅgulimāla's initial encounter with the Buddha and his conversion, and are believed to present the oldest version of the story.

[17] Later texts may represent attempts by later commentators to "rehabilitate" the character of Aṅgulimāla, making him appear as a fundamentally good human being entrapped by circumstance, rather than as a vicious killer.

[18][19] In addition to the discourses and verses, there are also Jātaka tales, the Milindapañhā, and parts of the monastic discipline that deal with Aṅgulimāla, as well as the later Mahāvaṃsa chronicle.

In this life, he was born as a man-eating king turned yaksha (Pali: yakkha, a sort of demon; Sanskrit: yakṣa),[27][28] in some texts called Saudāsa.

[32] In most texts, Aṅgulimāla is born in Sāvatthī,[29][note 3] in the brahman (priest) caste of the Garga clan, his father Bhaggava being the chaplain of the king of Kosala, and his mother called Mantānī.

[1][11] Following his teacher's bidding, Aṅgulimāla becomes a highwayman, living on a cliff in a forest called Jālinī where he can see people passing through, and kills or hurts those travelers.

[56] After listening to the Buddha, Aṅgulimāla reverently declares himself converted, vows to cease his life as a brigand and joins the Buddhist monastic order.

This passage would agree with Buddhologist André Bareau's observation that there was an unwritten agreement of mutual non-interference between the Buddha and kings and rulers of the time.

The Buddha tells Aṅgulimāla to go to the woman and say: Sister, since I was born, I do not recall that I have ever intentionally deprived a living being of life.

[1] [emphasis added]The Buddha is here drawing Angulimala's attention to his choice of having become a monk,[1] describing this as a second birth that contrasts with his previous life as a brigand.

Uttanka says to his teacher: What can I do for you that pleases you (Sanskrit: kiṃ te priyaṃ karavāni), because thus it is said: Whoever answers without [being in agreement with] the Dharma, and whoever asks without [being in agreement with] the Dharma, either occurs: one dies or one attracts animosity.Indologist Friedrich Wilhelm maintains that similar phrases already occur in the Book of Manu (II,111) and in the Institutes of Vishnu.

It is therefore not unusual that Aṅgulimāla is described to do his teacher's horrible bidding—although being a good and kind person at heart—in the knowledge that in the end he will reap the highest attainment.

[74] Indologist Richard Gombrich has postulated that the story of Aṅgulimāla may be a historical encounter between the Buddha and a follower of an early Saivite or Shakti form of tantra.

[75] Gombrich reaches this conclusion on the basis of a number of inconsistencies in the texts that indicate possible corruption,[76] and the fairly weak explanations for Aṅgulimāla's behavior provided by the commentators.

[77][78] He notes that there are several other references in the early Pāli canon that seem to indicate the presence of devotees of Śaiva, Kāli, and other divinities associated with sanguinary (violent) tantric practices.

In his travel accounts, Xuan Zang states that Aṅgulimāla's was taught by his teacher that he would be born in the Brahma heaven if he killed a Buddha.

A Chinese early text gives a similar description, stating that Aṅgulimāla's teacher followed the gruesome instructions of his guru, to attain immortality.

However, Gombrich's claim that tantric practices existed before the finalization of the canon of Buddhist discourses (two to three centuries BCE) goes against mainstream scholarship.

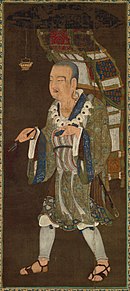

[4] In the Chinese translation of the Damamūkhāvadāna by Hui-chiao,[87] as well as in archaeological findings,[29] Aṅgulimāla is identified with the mythological Hindu king Kalmashapada or Saudāsa, known since Vedic times.

[29] Studying art depictions in the Gandhāra region, Archeologist Maurizio Taddei theorizes that the story of Aṅgulimāla may point at an Indian mythology with regard to a yakṣa living in the wild.

[41] She concurs with Taddei that depictions of Aṅgulimāla, especially in Gandhāra, are in many ways reminiscent of dionysian themes in Greek art and mythology, and influence is highly likely.

[88] However, Brancaccio argues that the headdress was essentially an Indian symbol, used by artists to indicate Aṅgulimāla belonged to a forest tribe, feared by the early Buddhists who were mostly urban.

[45] From a Buddhist perspective, Aṅgulimāla's story serves as an example that even the worst of people can overcome their faults and return to the right path.

[citation needed] Jungian analyst Dale Mathers theorizes that Ahiṃsaka started to kill because his meaning system had broken down.

[100] In Sri Lankan pre-birth rituals, when the Aṅgulimāla Sutta is chanted for a pregnant woman, it is custom to surround her with objects symbolizing fertility and reproduction, such as parts of the coconut tree and earthen pots.

[115] The book emphasizes the passage when the Buddha accepts Aṅgulimāla in the monastic order, effectively preventing King Pasenadi from punishing him.

In the end, however, the assembly decides to release the two, when Aṅgulimāla admits to his crimes and Pasenadi gives a speech emphasizing forgiveness rather than punishment.

[115] This twist in the story sheds a different light on Aṅgulimāla, whose violent actions ultimately lead to the trial and a more non-violent and just society.