List of animals of Yellowstone

Both stand approximately six feet tall at the shoulder, and can move with surprising speed to defend their young or when approached too closely by people.

Activities there included irrigation, hay-feeding, roundups, culling, and predator control, to artificially ensure herd survival.

Cutthroat trout are an important late-spring and early-summer food source for bears, providing them the opportunity to regain body mass after den emergence, and assisting females with cubs meet the energetic demands of lactation.

Bears were attracted to these areas by the availability of human foods in the form of handouts and unsecured camp groceries and garbage.

Although having bears readily visible along roadsides and within developed areas was very popular with park visitors, an average of 48 bear-caused human injuries occurred each year from 1930 through 1969.

[7] Over the next several decades, the bears learned to hunt and forage for themselves from non-human food sources, and their population slowly grew.

No research has been conducted in Yellowstone to determine the numbers or distribution of this elusive animal that usually is solitary, nocturnal, and widely scattered over its range.

A four-year study completed in 2005 concluded there is a small resident population of lynx in the park, but it is rarely seen directly or indirectly (tracks) by either biologists or visitors.

During planning and environmental assessment of the effects of wolf restoration, biologists anticipated that coyotes would compete with the larger canid, perhaps resulting in disruption of packs and numerical declines.

[11] Elk or wapiti (Cervus canadensis) are the most abundant large mammal found in Yellowstone; paleontological evidence confirms their continuous presence for at least 1,000 years.

Not until after 1886, when the United States Army was called in to protect the park and wildlife slaughter was brought under control, did the large animals increase in number.

The antlers are usually shed in March or April, and begin regrowing in May, when the bony growth is nourished by blood vessels and covered by furry-looking "velvet."

Antler growth ceases each year by August, when the velvet dries up and bulls begin to scrape it off by rubbing against trees, in preparation for the autumn mating season or rut.

A bull may gather 20-30 cows into his harem during the mating season, often clashing or locking antlers with another mature male for the privilege of dominating the herd group.

The fires forced some moose into poorer habitats, with the result that some almost doubled their home range, using deeper snow areas than previously, and sometimes browsing burned lodgepole pines.

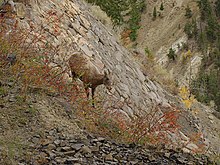

[15] Bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) were once very numerous in western United States and were an important food source for humans.

The mountain lion (Puma concolor), also called the cougar, is the largest member of the cat family living in Yellowstone.

The white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) occurs in aspen parklands and deciduous river bottomlands within the central and northern Great Plains, and in mixed deciduous riparian corridors, river valley bottomlands, and lower foothills of the northern Rocky Mountain regions from Wyoming to southeastern British Columbia.

[16] Northern Rocky Mountain wolves, a subspecies of the gray wolf (Canis lupus), were native to Yellowstone when the park was established in 1872.

By the 1970s, scientists found no evidence of a wolf population in Yellowstone; wolves persisted in the lower 48 states only in northern Minnesota and on Isle Royale in Michigan.

Squirrels, rabbits, skunks, raccoons, badgers, otters, beavers, porcupines, vole, mice, and shrew species are common, but many are nocturnal and rarely seen by visitors.

The park has a good resident population of bald eagles, trumpeter swans, common loons, ospreys, American white pelicans, and sandhill cranes.

The extensive rivers, lakes and wetlands are summer homes to large numbers of waterfowl, while the forests and meadows host many different species of warblers, sparrows and other passerine birds.

[25] Although no Yellowstone reptile or amphibian species are currently listed as threatened or endangered, several — including the boreal toad — are thought to be declining in the West.

Known reptile species in the park: prairie rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis viridis), bullsnake (Pituophis catenifer sayi), valley garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis fitchi), wandering garter snake (Thamnophis elegans vagrans), rubber boa (Charina bottae), sagebrush lizard (Sceloporus graciosus graciosus).

The relatively undisturbed nature of the park and the baseline data may prove useful in testing hypotheses concerning the apparent declines of several species of toads and frogs in the western United States.

Reptile and amphibian population declines may be caused by such factors as drought, pollution, disease, predation, habitat loss and fragmentation, introduced fish and other non-native species.

Yellowstone cutthroat trout generally declined in the second half of the 20th century due to angler overharvest, competition with exotic fishes, and overzealous egg collection.

Whirling disease, which has been implicated in recent years in the decline of trout populations in many western states, was discovered in Yellowstone Lake in 1998.

Yellowstone cutthroat trout have declined throughout the west and are currently designated as a "Species of Special Concern-Class A" by the American Fisheries Society.