Ontological argument

More specifically, ontological arguments are commonly conceived a priori in regard to the organization of the universe, whereby, if such organizational structure is true, God must exist.

The first ontological argument in Western Christian tradition[i] was proposed by Saint Anselm of Canterbury in his 1078 work, Proslogion (Latin: Proslogium, lit.

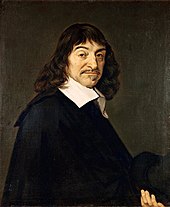

In the early 18th century, Gottfried Leibniz augmented Descartes' ideas in an attempt to prove that a "supremely perfect" being is a coherent concept.

Other arguments have been categorised as ontological, including those made by Islamic philosophers Mulla Sadra and Allama Tabatabai.

David Hume also offered an empirical objection, criticising its lack of evidential reasoning and rejecting the idea that anything can exist necessarily.

Contemporary defenders of the ontological argument include Alvin Plantinga, Yujin Nagasawa, and Robert Maydole.

[3] Graham Oppy, who elsewhere expressed that he "see[s] no urgent reason" to depart from the traditional definition,[3] defined ontological arguments as those which begin with "nothing but analytic, a priori and necessary premises" and conclude that God exists.

Craig argues that an argument can be classified as ontological if it attempts to deduce the existence of God, along with other necessary truths, from his definition.

He suggests that proponents of ontological arguments would claim that, if one fully understood the concept of God, one must accept his existence.

[1][10][11] Some scholars argue that Islamic philosopher Avicenna (Ibn Sina) developed a special kind of ontological argument before Anselm,[12][13] while others have doubted this position.

"[1] While Anselm has often been credited as the first to understand God as the greatest possible being, this perception was actually widely described among ancient Greek philosophers and early Christian writers.

Hegel signed a book contract in 1831, the year of his death, for a work entitled Lectures on the Proofs of the Existence of God.

He provided an argument based on modal logic; he uses the conception of properties, ultimately concluding with God's existence.

Gödel proposed that it is understood in an aesthetic and moral sense, or alternatively as the opposite of privation (the absence of necessary qualities in the universe).

He warned against interpreting "positive" as being morally or aesthetically "good" (the greatest advantage and least disadvantage), as this includes negative characteristics.

Paul Oppenheimer and Edward N. Zalta note that, for Anselm's Proslogion chapter 2, "Many recent authors have interpreted this argument as a modal one."

[38]Norman Malcolm and Charles Hartshorne are primarily responsible for introducing modal versions of the argument into the contemporary debate.

Jordan Sobel writes that Malcolm is incorrect in assuming that the argument he is expounding is to be found entirely in Proslogion chapter 3.

[38] Christian Analytic philosopher Alvin Plantinga[43] criticized Malcolm's and Hartshorne's arguments, and offered an alternative.

[56] According to Graham Oppy, the validity of this argument relies on a B or S5 system of modal logic, because they have the suitable accessibility relations between worlds.

A version of his argument may be formulated as follows:[29] Plantinga argued that, although the first premise is not rationally established, it is not contrary to reason.

Michael Martin argued that, if certain components of perfection are contradictory, such as omnipotence and omniscience, then the first premise is contrary to reason.

Plantinga anticipated this line of objection and pointed out in his defense that any deductively valid argument will beg the question this way.

[62] On systems of modal logic in general, James Garson writes that "the words ‘necessarily’ and ‘possibly’, have many different uses.

Prover9 subsequently discovered a simpler, formally valid (if not necessarily sound) ontological argument from a single non-logical premise.

[71] Thomas Aquinas, while proposing five proofs of God's existence in his Summa Theologica, objected to Anselm's argument.

[75] In his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, the character Cleanthes proposes a criticism: ...there is an evident absurdity in pretending to demonstrate a matter of fact, or to prove it by any arguments a priori.

[77] Immanuel Kant put forward an influential criticism of the ontological argument in his Critique of Pure Reason.

[81] Australian philosopher Douglas Gasking (1911–1994) developed a version of the ontological argument meant to prove God's non-existence.

Gasking's proposition that the greatest disability would be non-existence is a response to Anselm's assumption that existence is a predicate and perfection.