Anselm of Canterbury

Humbert's son Otto was subsequently permitted to inherit the extensive March of Susa through his wife Adelaide[11] in preference to her uncle's families, who had supported the effort to establish an independent Kingdom of Italy under William V, Duke of Aquitaine.

Otto and Adelaide's unified lands[12] then controlled the most important passes in the Western Alps and formed the county of Savoy whose dynasty would later rule the kingdoms of Sardinia and Italy.

[17] Following the death of his mother, probably at the birth of his sister Richera,[27] Anselm's father repented his own earlier lifestyle but professed his new faith with a severity that the boy found likewise unbearable.

His father having died, he consulted with Lanfranc as to whether to return to his estates and employ their income in providing alms for the poor or to renounce them, becoming a hermit or a monk at Bec or Cluny.

[33] Three years later, in 1063, Duke William II summoned Lanfranc to serve as the abbot of his new abbey of St Stephen at Caen[17] and the monks of Bec, despite the initial hesitation of some on account of his youth,[26] elected Anselm prior.

[26] There was also admiration for his spirited defence of the abbey's independence from lay and archiepiscopal control, especially in the face of Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester and the new Archbishop of Rouen, William Bona Anima.

[17] The gravely ill Hugh, Earl of Chester, finally lured him over with three pressing messages in 1092,[46] seeking advice on how best to handle the establishment of a new monastery at St Werburgh's.

[26] He then travelled to his former pupil Gilbert Crispin, abbot of Westminster, and waited, apparently delayed by the need to assemble the donors of Bec's new lands in order to obtain royal approval of the grants.

[26] On 6 March 1093, he further nominated Anselm to fill the vacancy at Canterbury; the clerics gathered at court acclaiming him, forcing the crozier into his hands, and bodily carrying him to a nearby church amid a Te Deum.

[73] When a group of bishops subsequently suggested that William might now settle for the original sum, Anselm replied that he had already given the money to the poor and "that he disdained to purchase his master's favour as he would a horse or ass".

[78] The king agreed to publicly support Urban's cause in exchange for acknowledgement of his rights to accept no legates without invitation and to block clerics from receiving or obeying papal letters without his approval.

[87] In the face of William's refusal to fulfill his promise of church reform, Anselm resolved to proceed to Rome—where an army of French crusaders had finally installed Urban—in order to seek the counsel of the pope.

Anselm wooed wavering barons to the king's cause, emphasizing the religious nature of their oaths and duty of loyalty;[102] he supported the deposition of Ranulf Flambard, the disloyal new bishop of Durham;[103] and he threatened Robert with excommunication.

[117] Anselm insisted on the agreement's ratification by the pope before he would consent to return to England, but wrote to Paschal in favour of the deal, arguing that Henry's forsaking of lay investiture was a greater victory than the matter of homage.

[118] On 23 March 1106, Paschal wrote Anselm accepting the terms established at L'Aigle, although both clerics saw this as a temporary compromise and intended to continue pressing for reforms,[119] including the ending of homage to lay authorities.

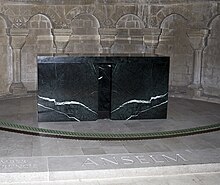

[111] His remains were translated to Canterbury Cathedral[126] and laid at the head of Lanfranc at his initial resting place to the south of the Altar of the Holy Trinity (now St Thomas's Chapel).

On 23 December 1752, Archbishop Herring was contacted by Count Perron, the Sardinian ambassador, on behalf of King Charles Emmanuel, who requested permission to translate Anselm's relics to Italy.

[129] The ambassador's own investigation was of the opinion that Anselm's body had been confused with Archbishop Theobald's and likely remained entombed near the altar of the Virgin Mary,[136] but in the uncertainty nothing further seems to have been done then or when inquiries were renewed in 1841.

[142][143][41] He or the thinkers in northern France who shortly followed him—including Abelard, William of Conches, and Gilbert of Poitiers—inaugurated "one of the most brilliant periods of Western philosophy", innovating logic, semantics, ethics, metaphysics, and other areas of philosophical theology.

"[f][146] Merely rational proofs are always, however, to be tested by scripture[149][150] and he employs Biblical passages and "what we believe" (quod credimus) at times to raise problems or to present erroneous understandings, whose inconsistencies are then resolved by reason.

[160] The Proslogion (Latin: Proslogium, "Discourse"), originally entitled Faith Seeking Understanding (Fides Quaerens Intellectum) and then An Address on God's Existence (Alloquium de Dei Existentia),[153][167][i] was written over the next two years (1077–1078).

[151] Anselm's De Grammatico ("On the Grammarian"), of uncertain date,[n] deals with eliminating various paradoxes arising from the grammar of Latin nouns and adjectives[155] by examining the syllogisms involved to ensure the terms in the premises agree in meaning and not merely expression.

[192] This interpretation is notable for permitting divine justice and mercy to be entirely compatible[163] and has exercised immense influence over church doctrine,[160][198] largely supplanting the earlier theory developed by Origen and Gregory of Nyssa[111] that had focused primarily on Satan's power over fallen man.

[160] Cur Deus Homo is often accounted Anselm's greatest work,[111] but the legalist and amoral nature of the argument, along with its neglect of the individuals actually being redeemed, has been criticized both by comparison with the treatment by Abelard[160] and for its subsequent development in Protestant theology.

[32] He claimed to have written it out of a desire to expand on an aspect of Cur Deus Homo for his student and friend Boso and takes the form of Anselm's half of a conversation with him.

De Processione Spiritus Sancti Contra Graecos ("On the Procession of the Holy Spirit Against the Greeks"),[167] written in 1102,[32] is a recapitulation of Anselm's treatment of the subject at the Council of Bari.

[160] De Concordia Praescientiae et Praedestinationis et Gratiae Dei cum Libero Arbitrio ("On the Harmony of Foreknowledge and Predestination and the Grace of God with Free Choice") was written from 1107 to 1108.

[217] Vaughn[218] and others argue that the "carefully nurtured image of simple holiness and profound thinking" was precisely employed as a tool by an adept, disingenuous political operator,[217] while the traditional view of the pious and reluctant church leader recorded by Eadmer—one who genuinely "nursed a deep-seated horror of worldly advancement"—is upheld by Southern[219] among others.

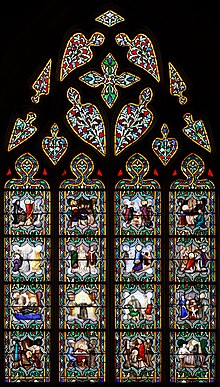

[222] A chapel of Canterbury Cathedral south of the high altar is dedicated to him; it includes a modern stained-glass representation of the saint, flanked by his mentor Lanfranc and his steward Baldwin and by kings William II and Henry I.

In 2015, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, created the Community of Saint Anselm, an Anglican religious order that resides at Lambeth Palace and is devoted to "prayer and service to the poor".