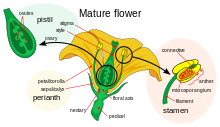

Stamen

The sterile tissue between the lobes is called the connective, an extension of the filament containing conducting strands.

The size of anthers differs greatly, from a tiny fraction of a millimeter in Wolfia spp up to five inches (13 centimeters) in Canna iridiflora and Strelitzia nicolai.

[2] The androecium in various species of plants forms a great variety of patterns, some of them highly complex.

Depending on the species of plant, some or all of the stamens in a flower may be attached to the petals or to the floral axis.

Each microsporangium is lined with a nutritive tissue layer called the tapetum and initially contains diploid pollen mother cells.

In some plants, notably members of Orchidaceae and Asclepiadoideae, the pollen remains in masses called pollinia, which are adapted to attach to particular pollinating agents such as birds or insects.

Pollen of angiosperms must be transported to the stigma, the receptive surface of the carpel, of a compatible flower, for successful pollination to occur.

Stamens can also be adnate (fused or joined from more than one whorl): They can have different lengths from each other: or respective to the rest of the flower (perianth): They may be arranged in one of two different patterns: They may be arranged, with respect to the petals: Where the connective is very small, or imperceptible, the anther lobes are close together, and the connective is referred to as discrete, e.g. Euphorbia pp., Adhatoda zeylanica.

The connective may also bear appendages, and is called appendiculate, e.g. Nerium odorum and some other species of Apocynaceae.

Stamens can be connate (fused or joined in the same whorl) as follows: Anther shapes are variously described by terms such as linear, rounded, sagittate, sinuous, or reniform.